Google search is continuously evolving into a full service provider, directly selecting and presenting the information that we are looking for. At first glance, this seems to benefit consumers. However, it can also harm competition because it gives Google the power to decide the success (or failure) of other websites by circumventing consumers’ choice. This has given rise to antitrust investigations and litigation in Germany.

When you are searching for the weather at your current location, all you need to do is visit google.com and enter the search term “weather.” Google will do the rest for you: not only will it show you a number of websites linked to your search term, but—at the very top of the results—it will directly give you a nice weather graph for your location, including temperatures, precipitation, and wind for the following days.

This is what Google calls a knowledge panel, and it illustrates how Google search went from a simple search engine to a “full service provider” (a development that is well-explained here). This can be quite handy for users, who don’t even have to click anywhere else to find the information. At the same time, it is to Google’s advantage, because users stay longer on Google, which can monetize the additional attention and time via advertising. Other websites’ operators might, however, not be amused: the more information users find directly on Google, the less they will make their way to other websites. Less visitors means less advertising revenue.

In Germany, Google’s evolution has raised antitrust concerns. First, a media company that runs a website with health-related information has filed a private lawsuit against Google and the German Ministry of Health over an info-box with health-related information that was sourced from the Ministry’s website and displayed on Google Search, reducing other health websites’ visitor numbers. Second, the German Competition Authority (“Bundeskartellamt”) has opened investigations into the Google News Showcase, a new Google service that shows news selected by Google in so-called “story panels,” somewhat similar to the knowledge panels.

Both cases serve to illustrate a novel theory of harm that I suggest calling “crowning the kings”: when Google directly shows information taken from other sources, it decides the success or failure of the websites that provide this information and thereby circumvents consumers as the arbiters of competition.

Google and the German Ministry of Health: the Ideal Symbiosis for Google

When Google includes information directly in the search results, it has to source it from somewhere. In Germany, it found the perfect partner for this: the Federal Ministry of Health. The ministry runs a national health portal (“gesund.bund.de”) to inform citizens about health-related information. It offers information on, inter alia, diseases, nutrition, care, or patient rights. The website is state-owned and financed.

Unlike privately-operated websites with similar offerings, the national health portal is therefore not dependent on ad revenues. This makes it the perfect partner for Google. Taking information from the health portal and showing it directly in the search results lets users stay longer on Google without cutting off ad revenue from the national health portal (since it never had any). This is exactly what Google did in November 2020: in collaboration with the German Ministry of Health, it created an info-box with health-related information, taken directly from the national health portal, prominently displayed on the search results page.

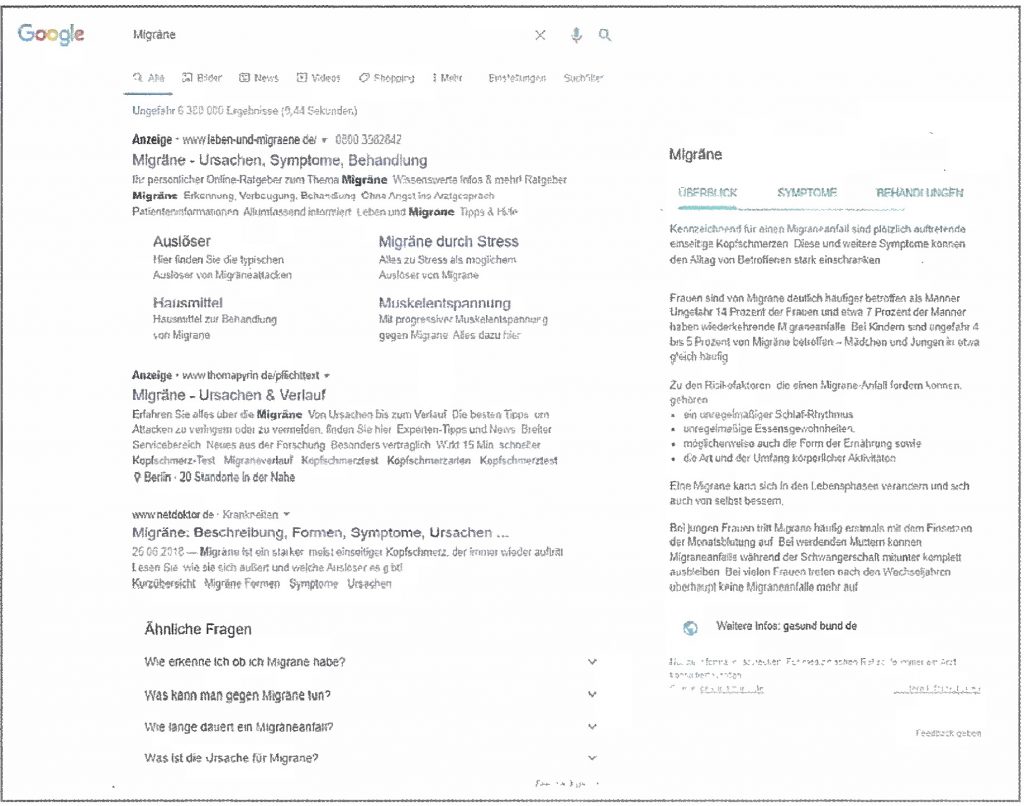

Search results for health-related information thereafter looked like this:

In this example, the search term was “Migräne” (migraine). On the right, there is the info-box with a link to the national health portal. On the left, following a few paid results, the first organic result appears. In this case, it is netdoktor.de, an ad-financed website that provides health-related information quite similar to gesund.bund.de. This website’s operator saw a sharp decline in user traffic and decided to challenge the info-box in court. In two separate lawsuits (one against Google, one against the Ministry) before a court in Munich, it demanded the collaboration ended on antitrust grounds, among others.

The court upheld the claim in a judgment from February this year (I discuss this in some more detail here). It found that the collaboration between Google and the Ministry of Health constitutes an anticompetitive agreement. The court argued that health portal operators are dependent on Google to make their services accessible. Only with good visibility on Google search can they generate sufficient user traffic to run their businesses. The info-box, as shown in the picture above, takes over the “prime real estate” on the search results page. In fact, the plaintiffs’ website was the only organic search result that could still be found on the first page of the results, albeit only at the very end.

The info-box has two effects: First, users often do not need to access any website apart from Google, if they can find what they were looking for already in the info-box. Second, those users who still wish to search further are more likely to use the prominently shown link to the national health portal within the info-box than to access those offers that are shown in the organic search results (i.e., websites like netdoktor.de). In both cases, the private health portals are left with less user traffic to monetize. Google, in turn, has its users staying longer, allowing the company to collect more data and sell more and better targeted (thus more valuable) advertising.

Google and the Ministry pled an “efficiency defense,” arguing that consumers actually benefitted from the info-box, which constituted an improvement in the quality of Google’s search results. Moreover, they argued, public health education was increased. This did not convince the court, which expressed concerns about Google’s shift from a (pure) search engine toward becoming a provider of content.

The court held that a qualitative improvement in Google’s service as such would not suffice for an efficiency gain to justify the behavior as it lacked an overall welfare increase. Here, the court stressed Google’s role as a “gatekeeper” in the upstream market, the low economic risk of the parties’ and, additionally, potential adverse effects on the plurality of media and opinion. In the long-term, so the concern, there could be no alternative health information provider left on the internet.

“with tools like the News Showcase, Google is able to circumvent consumers as the arbiters in the competitive process and thereby “crown the kings”.”

The Bundeskartellamt’s Investigation Into Google News Showcase

On June 4, the Bundeskartellamt announced that it has opened an investigation against Google for the recently launched Google News Showcase. In this investigation, the authority is flexing its muscles under a new tool that allows a special procedure against companies with paramount significance for competition across markets. The Bundeskartellamt is also investigating Facebook, Amazon and Apple under this tool.

Google News Showcase is a new service that was recently rolled out in several countries around the world that selects and shows news from certain publishers in so-called “story panels.” Google pays these publishers for being able to show their content. While the service was initially only available in the Google News app, it can now be found in Google News on the desktop. Interestingly, through Showcase, users are able to read even some articles that are normally paywalled. The Showcase (in Germany) looks like this:

The Bundeskartellamt is concerned that the “integration of Google News Showcase into Google’s general search function is likely to constitute self-preferencing or an impediment to the services offered by competing third parties.”

Theory of Harm: Crowning the Kings

One can wonder what the theory of harm in the two cases described above is. On the one hand, the info-box and the News Showcase obviously take away traffic from other websites. Yet, this seems to be in the interest of consumers: after all, it is easier for users to directly find information on health, or a nice selection of news articles (some of which would normally even be paywalled). Further, the idea of self-preferencing that the Bundeskartellamt suggests seems rather far-fetched. Unlike the Google Shopping case, where Google had a directly competing product—a shopping search engine with similar functionalities as the offers from price comparison sites like idealo or shopping.com—Google is not directly competing with news (or health) websites.

I suggest that the underlying theory of harm, applicable to both cases discussed above, is that with tools like the News Showcase, Google is able to circumvent consumers as the arbiters in the competitive process and thereby “crown the kings.” Ideally, it is the consumers who, through their consumption behavior, decide which offers succeed in the market. This element of competition is eliminated if Google can unilaterally decide which offers prevail. Due to Google’s market power, there is no pressure on the company to ensure that the “best” offers prevail (after all, if it is not by the consumer’s consumption decision, how can this be determined at all?). Google can thus effectively reduce competition between other website providers by selecting one (in the case of the health info-box) or several (in the case of the News Showcase) winners who are prominently displayed, leaving all other competitors in the rain. This can make the affected markets to “winner(s) take all” markets with the winner(s) being determined at the unchecked discretion of Google. In the context of news, this is particularly harmful since it could undermine plurality of opinion.

This theory of harm reflects a broader understanding of competition law, protecting the competitive process as well as consumer choice as an important element thereof. In Europe, and even more so in Germany, this view is not uncommon. The German Federal Supreme Court most recently stressed this aspect of competition law in the famous Facebook case.

Google will have to carefully design any new feature so as not to create winner-take-all markets and to uphold consumer’s ability to choose between different offers. In the context of the News Showcase, it seems likely that only giving non-discriminatory access for all publishers, including smaller and less well-known companies or new entrants, will be compatible with (European) competition law.