The US health care system is based on markets, which do not function as well as they could, or should. Prices are high and rising, there are egregious pricing practices, quality is suboptimal, and the sector is sluggish and unresponsive. Lack of competition has a lot to do with these problems.

Editor’s note: The following is based on testimony given before the Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights on May 19.

Health care is a very large and important industry. Health care spending is now over $3.8 trillion ($11,582 per person) and accounts for 17.7 percent of national income (measured as gross domestic product; GDP)—nearly one-fifth of the entire US economy and larger than the entire economy of France. Hospital services are a large part of the US economy. In 2019, hospital care alone accounted for 31.4 percent of total health spending and 5.6 percent of GDP—approximately the same size as the entire information sector or retail trade sector, and larger than the construction or transportation sectors. By comparison, physician services comprise 20.3 percent of health spending and 3.6 percent of GDP, pharmaceuticals account for 9.7 percent of health spending and 1.7 percent of GDP, and health insurance is 6.3 percent of health spending and approximately 1 percent of GDP. Moreover, the share of the economy accounted for by these sectors has risen dramatically over the last 30 years. In 1980, hospitals and physicians accounted for 3.6 percent and 1.7 percent of US GDP, respectively, while the net cost of health insurance in 1980 was 0.34 percent.

Of course, health care is important not only because of its size. Health care services can save lives or dramatically affect the quality of life, thereby substantially improving well being and productivity.

As a consequence, the functioning of the health care sector is vitally important. A well functioning health care sector is an asset to the economy and improves quality of life for the citizenry. By the same token, problems in the health care sector act as a drag on the economy and impose a burden on individuals.

The US health care system is based on markets. The vast majority of health care is privately provided (with some exceptions, such as public hospitals, the Veterans Administration, and the Indian Health Service) and over half of health care is privately financed. As a consequence, the health care system will only work as well as the markets that underpin it. If those markets function poorly, then we will get health care that’s not as good as it could be and that costs more than it should. Moreover, attempts at reform, no matter how important or clever, will not prove successful if they are built on top of dysfunctional markets.

“The health care system will only work as well as the markets that underpin it.”

There is widespread agreement that these markets do not work as well as they could, or should. Prices are high and rising. They vary in seemingly incoherent ways. There are egregious pricing practices. There are serious concerns about the quality of care, and the system is sluggish and unresponsive, lacking the innovation and dynamism that characterize much of the rest of our economy.

One of the reasons for this is lack of competition. The research evidence shows that hospitals that face less competition charge higher prices to private payers, without accompanying gains in efficiency or quality. Moreover, the evidence also shows that lack of competition can cause serious harm to the quality of care received by patients, even substantially increasing the risk of death.

It’s important to recognize that the burden of higher provider prices falls on individuals, not insurers or employers. Health care is not like commodity products, such as milk or gasoline. Consumers experience increases in the prices of common products like this directly when they purchase them. However, even though individuals with private employer-provided health insurance pay a small portion of provider fees directly out of their own pockets, they end up paying for increased prices in the end. Insurers facing higher provider prices increase their premiums to employers. Employers then pass those increased premiums on to their workers, either in the form of lower wages (or smaller wage increases) or reduced benefits (greater premium sharing, greater cost-sharing, or less extensive coverage). Employers may also respond to these increases in their costs of employing workers by reducing workers’ hours or the number of workers. A recent study finds that “hospital mergers lead to a $521 increase in hospital prices, a $579 increase in hospital spending among the privately insured population and a … $638 reduction in wages.”

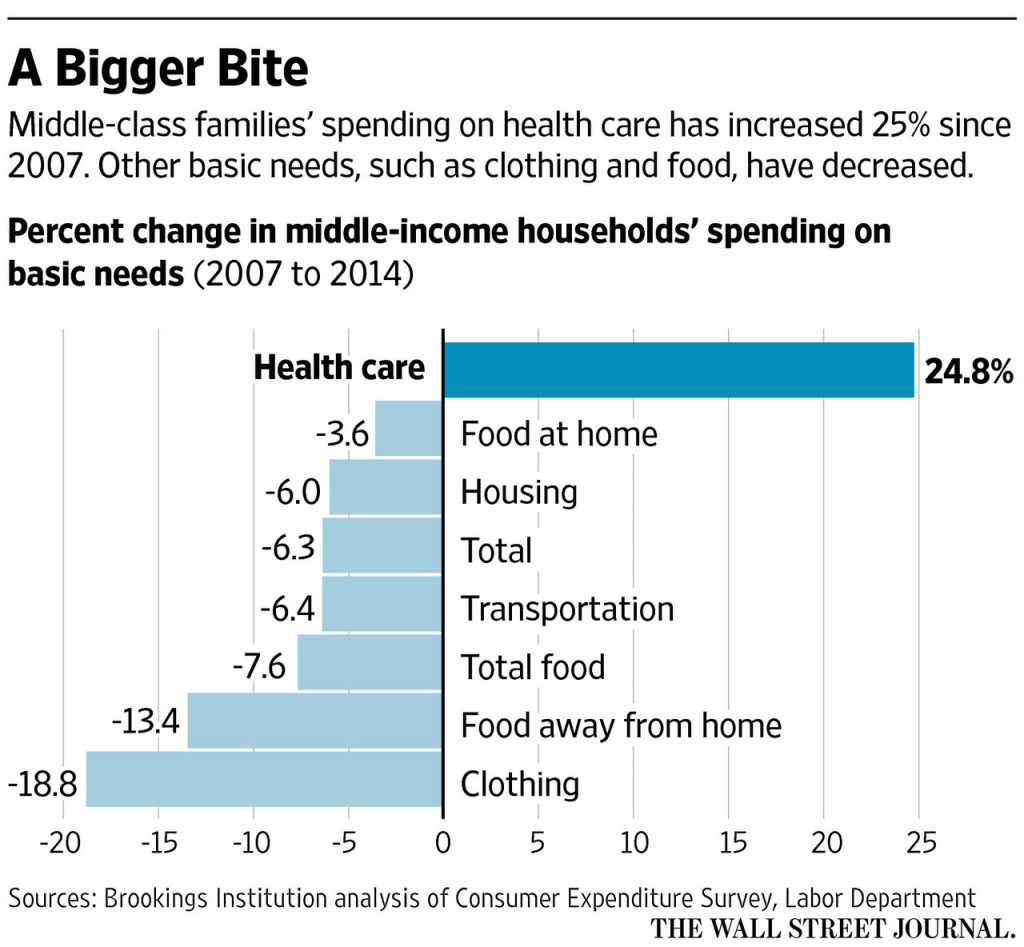

The burden of private health care spending on US households has been growing, so much so that it’s taking up a larger and larger share of household spending and exceeding increases in pay for many workers. Figure 1 illustrates this. Workers’ contributions to health insurance premiums grew 259 percent from 1999 to 2018, while wages grew by only 68 percent. Figure 2 illustrates that middle class families’ spending on health care has increased 25 percent since 2007, crowding out spending on other goods and services, including food, housing, and clothing. Health insurance fringe benefits for workers, chief among which is health care, increased as a share of workers’ total compensation over this same period, growing from 12 to 14.5 percent, while wages stayed flat.

Consolidation

There has been a tremendous amount of consolidation in the health care industry over the last 20 years. A recent paper by Brent D. Fulton documents these trends and shows high and increasing concentration in US hospital, physician, and insurance markets.

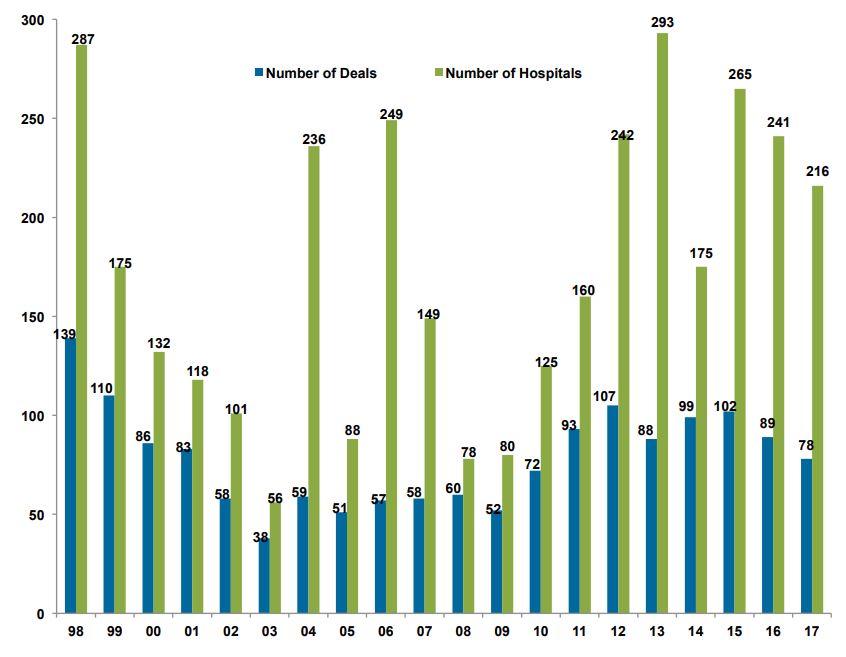

The American Hospital Association documents 1,577 hospital mergers from 1998 to 2017, with 456 occurring over the five years from 2013 to 2017. Figure 3 illustrates the number of mergers and the number of hospitals involved in these transactions from 1998 to 2017. KaufmanHall documents an additional 261 announced hospital mergers from 2018-2020.

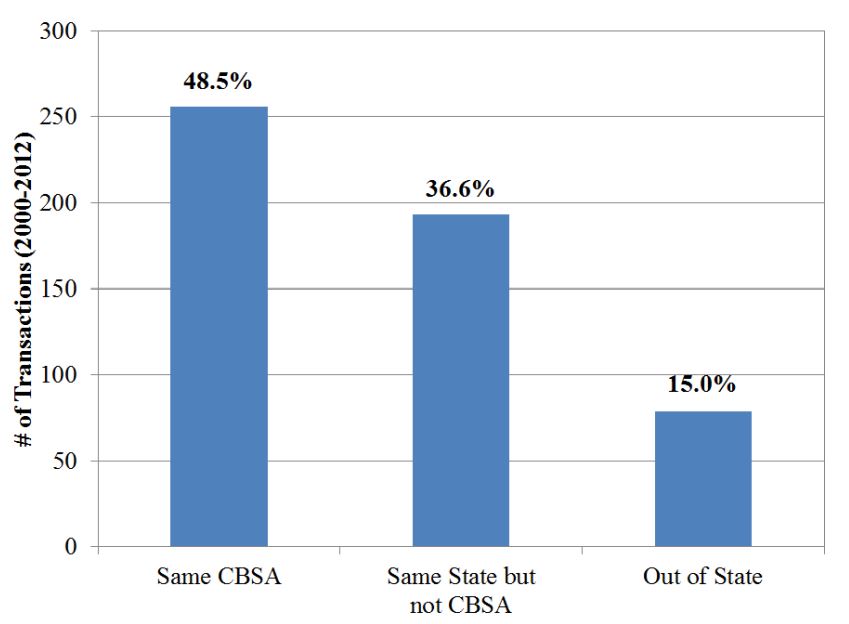

While some of these mergers may have little or no impact on competition, many include mergers between close competitors, especially given that hospital markets are already highly concentrated. Figure 4 shows that almost half of the hospital mergers occurring from 2010 to 2012 were between hospitals in the same area. Further, as indicated below, recent evidence indicates that even mergers between hospitals in different areas may lead to higher prices.

As a result of this consolidation, the majority of hospital markets are highly concentrated, and many areas of the country are dominated by one or two large hospital systems with no close competitors. This includes places like Boston (Partners), Cleveland (Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital), Pittsburgh (UPMC), and San Francisco (Sutter). Mergers that eliminate close competitors cause direct harm to competition. In addition, once a firm has obtained a dominant position it has an incentive to maintain or enhance it, including by engaging in anticompetitive practices.

Moreover, there have been a very large number of acquisitions of physician practices by hospitals. In 2006, 28 percent of primary physicians were employed by hospitals. By 2016, that number had risen to 44 percent. The American Medical Association reports that 33 percent of all physicians were employed by hospitals in 2016, and less than half own their own practice. Fulton finds that increased concentration in primary care physician markets is associated with practices owned by hospitals. Shruthi Venkatesh documents nearly 31,000 physician practice acquisitions by hospitals from 2008-2012, and that over 55 percent of physicians are in hospital owned practices.

It’s important to note that the vast majority of physician practice mergers and many hospital acquisitions of physician practices are not reported to the federal antitrust enforcement agencies, because these transactions are too small to fall under the Hart-Scott-Rodino reporting guidelines. Consideration should be given to adopting simple, streamlined reporting requirements for smaller transactions so that the enforcement agencies are able to properly track them and consider whether any are of concern.

There are a number of possible motivations for hospital mergers. Among these are an attempt to increase market power, and thereby enhance negotiating positions with private insurers, a desire to reduce costs, a desire to enhance quality, a desire to enhance coordination or integration of care, reactions to the mergers of rival hospitals or of insurers, an attempt to achieve protection against an uncertain environment, and spending excess cash.

My testimony from yesterday’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on hospital consolidation and what to do about it is here https://t.co/P0dqwtd9Eq. Video of the hearing and the other witnesses’ testimony is available here https://t.co/y1l2V7QlvM

— Martin Gaynor (@MartinSGaynor) May 20, 2021

Evidence on the Impacts of Consolidation

It’s important to be clear that consolidation can be either beneficial or harmful. Consolidation can bring efficiencies—it can reduce inefficient duplication of services, allow firms to combine to achieve efficient size, or facilitate investment in quality or efficiency improvements. Successful firms may also expand by acquiring others. If firms get larger by being better at giving consumers what they want or driving down costs so their goods are cheaper, that’s a good thing (big does not equal bad), so long as they don’t engage in actions to then attempt to limit competition. On the other hand, consolidation can reduce competition and enhance market power and thereby lead to increased prices or reduced quality. Moreover, firms that have acquired market power have strong incentives to maintain or enhance it. This leads to the potential for anticompetitive conduct by firms that have acquired dominant positions through consolidation.

There are many studies of hospital mergers. These studies look at many different mergers in different places in different time periods, and find substantial increases in price resulting from mergers in concentrated markets. Price increases on the order of 20 or 30 percent are common, with some increases as high as 65 percent.

These results make sense. Hospitals’ negotiations with insurers determine prices and whether they are in an insurer’s provider network. Insurers want to build a provider network that employers (and consumers) will value. If two hospitals are viewed as good alternatives to each other by consumers (close substitutes), then the insurer can substitute one for the other with little loss to the value of their product, and therefore each hospital’s bargaining leverage is limited. If one hospital declines to join the network, customers will be “almost as happy” with access to the other. If the two hospitals merge, the insurer will now lose substantial value if they offer a network without the merged entity (if there are no other hospitals viewed as good alternatives by consumers). The merger therefore generates bargaining leverage and hospitals can negotiate a price increase.

“Merged hospitals, insurers, physician practices, or integrated systems are not systematically less costly, higher quality, or more effective than independent firms.”

Overall, these studies consistently show that when hospital consolidation is between close competitors it raises prices, and by substantial amounts. Consolidated hospitals that are able to charge higher prices due to reduced competition are able to do so on an ongoing basis, making this a permanent rather than a transitory problem. Moreover, there is no difference between not-for-profit and for-profit hospitals in the extent to which they raise prices due to increased market power.

There is also more recent evidence that mergers between hospitals that are not near to each other can lead to price increases. Quite a few hospital mergers are between hospitals that are not in the same area (see Figure 4). Many employers have locations with employees in a number of geographic areas. These employers will most likely prefer insurance plans with provider networks that cover their employees in all of these locations. An insurance plan thus has an incentive to have a provider network that covers the multiple locations of employers. It is therefore costly for that insurer to lose a hospital system that has hospitals in multiple locations—their network would become less attractive. This means that a merger between hospitals in these different locations can increase their bargaining power, and hence their prices.

Studies that examine the impacts of hospital acquisitions of physician practices find that such acquisitions also result in significantly higher prices and more spending. For example, one 2018 study found that hospital acquisitions of physician practices led to prices increasing by an average of 14 percent and patient spending increasing by 4.9 percent.

Just as important, if not more, than impacts on prices are impacts on the quality of care. The quality of health care can have profound impacts on patients’ lives, including their probability of survival. A number of studies have found that patient health outcomes are substantially worse at hospitals in more concentrated markets, where those hospitals face less potential competition. One study found that Medicare patients who had suffered heart attacks were 1.46 percent more likely to die if they were treated at a hospital facing the least amount of potential competition, compared to patients treated at hospitals facing the greatest potential competition.

“It is important to realize that consolidation is not integration.”

It is plausible that consolidation between hospital, physician practices or insurers, in a number of combinations, could reduce costs, increase care coordination, or enhance efficiency. There may be gains from operating at a larger scale, eliminating wasteful duplication, improved communications, enhanced incentives for mutually beneficial investments, etc. However, it is important to realize that consolidation is not integration. Acquiring another firm changes ownership, but in and of itself does nothing to achieve integration. Integration, if it happens, is a long process that occurs after acquisition.

While the intuition, and the rhetoric, surrounding consolidation, has been positive, the reality is less encouraging. The evidence on the effects of consolidation is mixed, but it’s safe to say that it does not show overall gains from consolidation. Merged hospitals, insurers, physician practices, or integrated systems are not systematically less costly, higher quality, or more effective than independent firms.

After more than three decades of extensive consolidation in health care, it seems likely that the promised gains from consolidation would have materialized by now if they were truly there.