A new paper finds that media coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic, including vaccine development, tends to be more negative in the US than elsewhere. A striking 91 percent of major US media articles are predicted to be negative compared to 54 percent for major international outlets.

By January 2020, vaccine researchers and their government partners achieved a remarkable feat: six million Americans received a coronavirus vaccine just ten months after the first US cases were reported. This good news might have been surprising to major American media consumers, considering that, as we show in a recent working paper, 84 percent of coronavirus vaccine articles published since spring by the top fifteen US media sources have been negative in tone and pessimistic on vaccine developments, compared to 24 percent of vaccine articles published in other countries’ major English-language sources. Our study shows that major US outlets are extreme outliers in their pessimistic coverage of the vaccine and the pandemic more broadly. Their negativity may have real costs.

In mid-February, the Daily Mail reported that Dr. Sarah Gilbert and her colleagues at Oxford’s Jenner Institute were working on a vaccine for the novel coronavirus and were optimistic that it could be ready “within months.” US major media outlets such as Fox News, CNN, the New York Times, and the Washington Post did not report on Dr. Gilbert’s work until trials began in April. Even when they did, the stories often emphasized caveats about their optimistic timeline.

In September, only half of Americans surveyed were willing to take an approved vaccine if it were available then; fortunately, that share is now rising. Just months into the pandemic, 53 percent of Americans reported that stress over the Covid-19 pandemic had worsened their mental health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned against excessive consumption of pandemic news stories. We suspect that overwhelmingly negative US media coverage could be related to rising depression rates and unwillingness to take the vaccine.

We analyzed the text of roughly 20,000 articles and television transcripts to compare the tone of Covid-19 stories among US major media outlets (the top fifteen most read or viewed TV and newspaper outlets), other US outlets, scientific journals, major international outlets, and other international outlets. International mainstream outlets include highly trafficked outlets in English speaking countries like Canada, the UK, Australia, etc. These include outlets such as CTV and Globe and Mail in Canada, or The Hindu Times and Times of India in India. We separately examined coverage of vaccines, re-openings, and increases or decreases in case counts.

We used two alternative measures of negativity. First, we counted the fraction of words in an article that were negative based on widely used dictionaries of negative words. Second, we used a machine learning process to determine which words were most predictive of a positive or negative article based on an initial sample of articles classified as positive or negative by research assistants, and then predicted each article’s negativity in the larger sample.

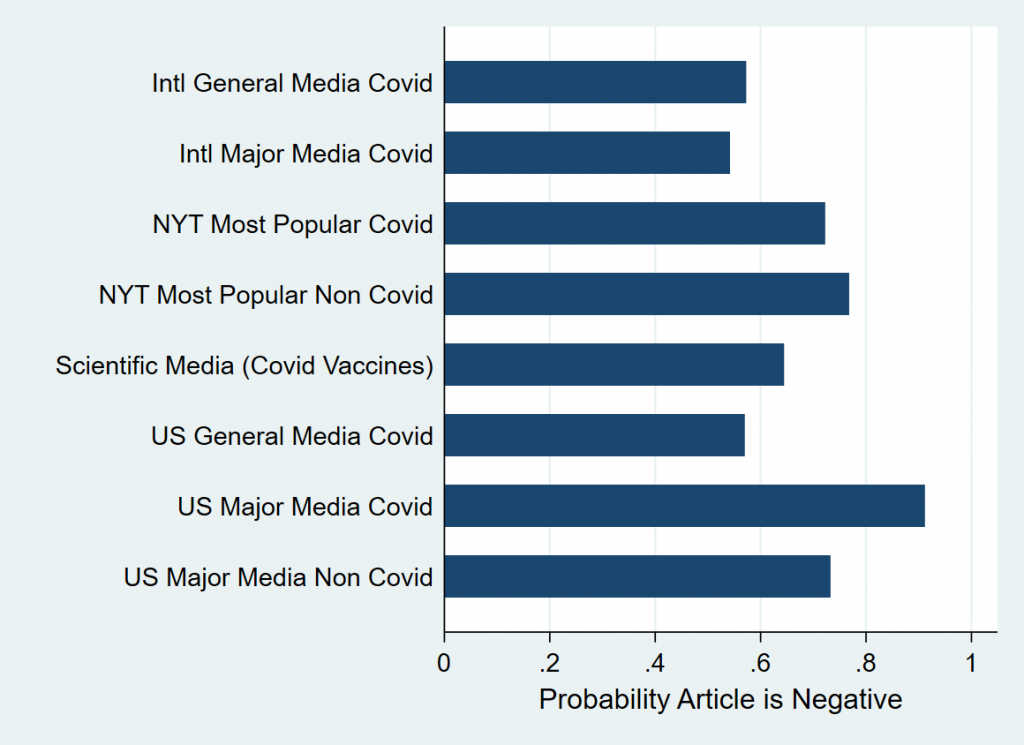

We find that the coverage of major American outlets’ is intensely negative relative to other sources. In Figure 1 below, we compare the estimated probability that a coronavirus article is negative across sources. Some may argue that this coverage is justified given 375,000 Americans have lost their lives. That being said, in figure 2 we show that American mainstream media negativity does not correlate with changes in case counts. A striking 91 percent of major US media articles are predicted to be negative compared to 54 percent for major international outlets and 57 percent for US general media sources. (Deaths per million people are similar in the US, UK, Italy, Spain and France.) The difference in tone is similarly large when we focus on potentially positive topics such as vaccines.

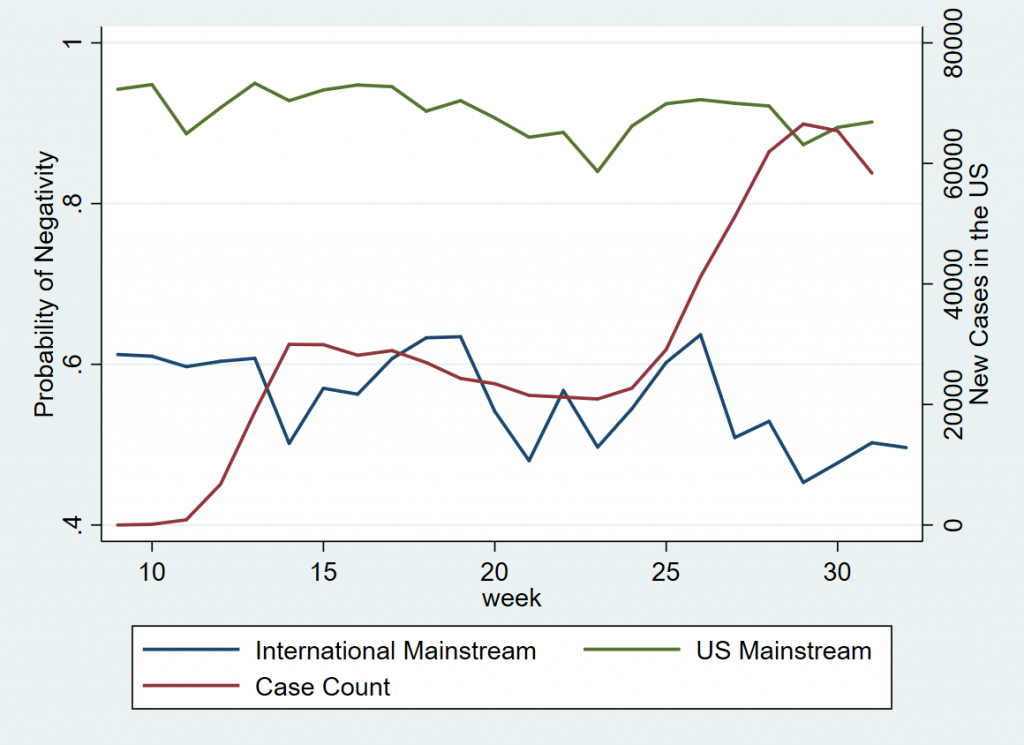

Interestingly, major US outlets’ negativity is largely unresponsive to changes in new US coronavirus cases. Figure 2 presents a weekly time series of negativity for major US and international outlets alongside new US cases. Major US outlets’ negativity remains high over the period when new cases fell from April to June and does not increase substantially when average daily cases rise from 20,000 to 60,000 in June and July.

Although some may wish to dismiss the media’s negativity as politically motivated, we find no evidence that negativity is related to audiences’ political leanings; for example, Fox News is at least as negative as CNN.

What can explain the gap between major US outlets’ negativity and that of international or scientific sources? The data suggest that viewers might demand or pay attention to more negative news. In our paper, we show that the “most-read” stories on the New York Times website related to Covid-19 have a substantially larger share of negative words than all other categories, including major US outlets overall. However, the “most-read” stories from the New York Times, are modestly less likely to be negative than stories from the American mainstream media. This also holds for the “most-read” articles unrelated to the coronavirus.

Reports on school re-openings have followed a similar pattern to those about vaccines. Dr. Emily Oster has gathered data on infection rates among students and staff across school districts. Her research and that of other scientists show that schools have not become the super spreaders many feared. Despite this, we find that up until July 31, when our current analysis cuts off, major US outlets’ coverage of school re-openings has been significantly more negative than research would suggest.

We are concerned about the possible consequences of major US outlets’ dire tone in areas with positive developments for public health and policymaking. Many Americans remain skeptical of coronavirus vaccines. Many districts have kept schools closed despite generally low infection rates in districts with in-person schooling. This may have serious implications for students’ learning; a recent study projected that spring school closures caused students to return to school in the fall with 63 to 68 percent of typical reading gains and 37 to 50 percent of typical math gains. The phenomenon of “doomscrolling” continues to exacerbate the stress of the pandemic.