Meet the Florida-based Fanjul brothers, who inject money to both political parties and dominate an industry that enjoys billions of dollar’s worth of subsidies and protections.

Last week, historical documents were released showing that the sugar industry paid Harvard scientists in the 1960s to produce research that downplayed the connection between sugar and heart disease, and instead laid the blame on saturated fat. According to The New York Times, the documents, released by a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, suggested that five decades of scientific research into the interconnection between nutrition and heart disease “may have been largely shaped by the sugar industry.”((Anahad O’connor, “How the Sugar Industry Shifted Blame to Fat,”. The New York Times, September 12, 2016.))

The recent revelations were in line with the industry’s repeated attempts to play down the health risks involved with increased sugar consumption. In the 1970s, as scientists and media began to connect sugar with illnesses such as obesity and diabetes, the Sugar Association— an industry trade group—ran a successful PR campaign that even led the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association to approve sugar as part of a healthy diet.((Gary Taubes and Cristin Kearns Couzens, “Big Sugar’s Sweet Little Lies.” Mother Jones, December 2012.))

Over the years, the industry has also invested heavily in lobbying and political contributions, using its influence with legislators to deter regulatory oversight. In 2003, for instance, when the World Health Organization recommended that people reduce the amount of sugar they consume, American sugar companies threatened to appeal to Congress to cut the WHO’s funding.((Sarah Boseley, “Sugar Industry Threatens to Scupper WHO.” The Guardian, April 2003.))

The recent revelations regarding the way the sugar industry influenced scientific research serve as a backdrop to the industry’s ongoing political activity. While the rift between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump continues to deepen, there is at least one place they can both turn to for support: the Florida-based Fanjul brothers, who just last month hosted fundraiser events for both Trump and Clinton–separately of course, and without much media attention.((Jerry Iannelli, “Big Sugar’s Fanjul Family Hosting Miami Fundraisers for Both Clinton and Trump This Year.” Miami New Times, August 2016.)) A close examination of the brothers’ businesses, and their ties to both parties and sugar regulation and laws, can serve as a classic case study of the way special interests operate within the political economy in the U.S.

The Fanjuls are most well-known for being sugar barons. Prior to fleeing Cuba and settling in Florida following Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution, the family had, over generations, amassed a fortune through growing and marketing sugar. When they moved to the U.S. they kept this business tradition alive, and with great success: the family bought lands, planted sugar canes, built factories, created partnerships, and expanded to other countries. The Fanjuls own about 400,000 acres of sugar cane plantations, half of which are in Florida and the other half in the Dominican Republic. Their main sugar holding company is American Sugar Refining, Inc. (ASR), which is a partnership between the Fanjul family’s Florida Crystals and the Sugar Cane Growers Cooperative of Florida. American Sugar Refining controls refineries by ownership or shareholder status in four states and six countries. The company’s American brands include Domino, Florida Crystals, Redpath, Tate & Lyle, and C&H.

Sugar is a commodity, which means its price is set in big international markets and is supposed to be pretty much the same all over the world. But in the U.S., the price of sugar has been greater than in other parts of the world, sometimes two or three times more. This significant markup is the result of U.S. laws and regulations.

The main policy tool the federal government uses to intervene in the sugar market is called the U.S. Sugar Program, which began in 1934. It supplies cane and beet growers with subsidized loans, and limits imports through tariffs and by setting local selling quotas if imports fall below a certain floor.

The dollar value of this federal support is considerable. A May 2013 working paper by John Beghin and Amani Elobeid from Iowa State University’s Center for Agricultural and Rural Development estimated that abolishing the program would result in $2.9B to $3.5B in consumer welfare each year.((John Beghin and Amani Elobeid, “The Impact of the U.S. Sugar Program Redux,” Working Paper 13-WP 538 (2013).))

The paper also concluded that discontinuing the program would result in an addition of 17,000 to 20,000 new jobs in sugar production and related industries, and that imports of products containing sugar would fall dramatically as, currently, these products contain sugar bought in international markets and are used to circumvent the higher cost of sugar in the U.S.

Beghin and Elobeid describe sugar subsidies as a classic rivalry between concentrated interests and the public. Consumer welfare savings per person are expected to be small, about $10, and “this small individual amount is typical of rent-seeking situations with diffuse losses for individual consumers and concentrated gains for producers.”

Sugar is only one of many industries in the United States that receive corporate welfare, subsidies, and support. But unlike most other industries, in the sugar industry a significant part of the benefits flows to one private business group that has a dominant position in the industry–the sugar empire of the Fanjul family. According to re

ports,((Elaina Plott, “Marco Rubio’s Billion-Dollar Sugar Addiction.” National Review, November 2015.)) few have benefited more from industry subsidies than the Fanjuls, whose American Sugar Refining is the largest sugar-processing conglomerate in the world.

While 60 percent of U.S. sugar production originates from beets, the remaining 40 percent comes from canes. Over the years, sugar imports have grown as well—including imports from the Dominican Republic, where the Fanjuls are the biggest growers and exporters. The Dominican Republic is one of the top exporters of sugar to the U.S., and 63 percent of the country’s sugar export quota to the U.S. is allocated to the Fanjul family.

In 2010, when the family celebrated 50 years of operation in the U.S., Florida Crystals had grown to 187,000 acres of sugar cane, employed about 2,000 people in Palm Beach County alone, and was expected to produce 660,000 tons of sugar. The family’s subsidiaries and affiliates at the time owned four raw sugar mills and 10 sugar refineries in six countries worldwide.

As the Fanjuls’ companies are private, no public data is available regarding their revenues or profitability. Nevertheless, a September 2008 New York Times article stated that “…the company said it had revenue of $3 billion last year, up from $2.5 billion the year before.” A 1987 Chicago Tribune article estimated the family’s net worth at $500 million, but in recent press articles they are often referred to as billionaires.

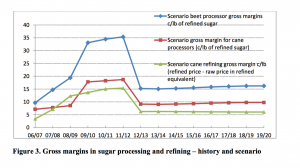

Discontinuing the Sugar Program would drastically hurt the Fanjul family. Beghin and Elobeid estimate that its discontinuation would cause the gross margin in cane sugar production to drop from as high as 35 percent in 2012 (the year prior to the paper’s publication) to as low as 15 percent.

“Gross margins of sugar crop growers and processors,” Beghin and Elobeid write, “had increased sharply with full implementation of the 2008 farm bill during 2009/10-2011/12. They were up by an average of $4.0 billion per year to $7.4 billion. With the reform, in the projection period they fall back closer to the $3.4 billion average that prevailed during 2006/07-2008/09, averaging just below $4 billion for 2012/13 to 2019/20.”

The issue of whether or not to keep the Sugar Program in place is not theoretical: by year-end, U.S. lawmakers have to decide on billions of dollars of cuts in agriculture spending.

As expected, the struggle is complex and full of special interests and lobbyists on both sides. Confectionary producers support putting an end to the Sugar Program. The various groups are pushing their lobbyists in opposite directions, and lawmakers are square in the middle of it.

The Fanjuls and the sugar industry are probably doing a very good job at lobbying. In a December 2013 Washington Post article, Peter Wallsten and Tom Hamburger quote a lobbyist close to sugar executives who said: “the sugar guys win votes because they are better at politics than anyone else.”((Peter Wallsten and Tom Hamburger, “Sugar Protections Prove Easy to Swallow for Lawmakers on Both Sides of Aisle.” Washington Post, December 2013.)) And they do it with little fanfare and few ears: “they come to Washington often, meet quietly with individual members, usually without staff present.” And in big numbers–Wallsten and Hamburger write that “in addition to the Fanjuls, the industry has retained a core of lobbyists, experts, and other advocates that could ‘fill a stadium,’ as one lobbyist put it.”

On top of their federal lobbying and contributions, the Fanjuls are also very active in local politics. According to a review of state election records by the Miami Herald and the Tampa Bay Times, the sugar industry—led by United States Sugar and Florida Crystals—gave $57.8 million in direct and in-kind contributions to state and local political campaigns between 1994 and 2016.((The Associated Press, “Report: Political Donations Show Sugar’s Clout in Florida.” July 2016.)) Florida Crystals and its affiliates contributed $12.4 million in the same period. In the current election cycle, the Fanjuls raised approximately $100,000 for the congressional campaign of retired Army Sergeant Brian Mast in Florida’s 18th District.

But nevertheless, the continuation of the program had–and still has–broad support. Some of its biggest supporters are prominent figures in both the Democratic and Republican parties, such as Democratic Senator Al Franken and former DNC chairperson Debbie Wasserman Schultz, as well as Republican Senator Marco Rubio, and Congressman Michael Conaway.

In many cases, members of Congress who oppose abolishing the program come from states where there are many sugar growers and refineries. This is not unusual–many industries have states where they are prominent. However, since the sugar industry only makes up a tiny fraction of the U.S. economy, there are not necessarily enough members of Congress from sugar-producing states to secure a favorable vote. More may be needed in order to reach the desired outcome.

The Fanjul brothers’ fundraisers for Clinton and Trump represent one of the peaks of decades of long, concentrated, focused, and sophisticated efforts by the family.

The family’s patriarchs are brothers Jose “Pepe” Fanjul and Alfonso “Alfy” Fanjul. Pepe is a long-time Republican Party supporter and Alfy is a long-time Democratic Party supporter. It is not unheard of for siblings to have opposing political views, but this is only one layer of the story.

Alfy Fanjul’s strong bonds with the leadership of the Democratic Party in general–and Bill and Hil

lary Clinton specifically–developed many years ago, as early as 1992. That year, Alfy Fanjul was the co-chair of Bill Clinton’s Florida campaign.((Amy Bracken, “A Sweet Deal: The Royal Family of Cane Benefits From Political Giving.” Al Jazeera America, July 2015.)) Just how close they were became apparent when it was revealed that then-President Clinton was on the phone with Alfy Fanjul on February 12, 1996, when the former was with Monica Lewinsky.((Eric Pooley, “High Crimes? Or Just a Sex Cover-Up?”. Time magazine, 1998.))

Later, Alfy Fanjul extended his support to Hillary Clinton as well. Ahead of the 2008 elections he contributed to her campaign, and in January 2015 he hosted both Hillary and Bill Clinton in his Dominican Republic mansion. Alfy Fanjul also held a fundraiser for Hillary Clinton on August 9, where participants paid $50,000 per plate.((George Bennett, “On Miami Stop, Hillary Clinton to Get Update on Zika Fight.” Palm Beach Post, August 2016.))

Alfy’s brother, Pepe, has contributed directly, and organized others to contribute millions of dollars to Republican politicians. He was one of the biggest supporters of and contributors to George W. Bush, and was one of the leading patrons of Marco Rubio. Last July, he co-hosted a big fundraiser for Donald Trump in the Hamptons.((Kevin Cirilli, Jennifer Jacobs. “Top Rubio, Bush Backers Among Co-Hosts for Trump Hamptons Fundraiser.” Bloomberg, July 2016.))

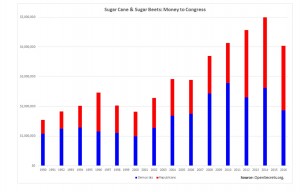

The Fanjul brothers also work with the rest of the sugar industry, and together they donate to politicians in big numbers: according to the Center for Responsive Politics, between 1990 and 2016, the sugar industry spent over $40 million on contributions to politicians.((Opensecrets.org)) The industry’s contribution strategy is similar to that of the Fanjul brothers, in that it has no significant preference for either party–Democratic politicians received 57 percent of the donations, Republicans received 43 percent.

The Fanjul brothers and their extended family also make direct contributions. Since 1990, they made contributions of $5 million to a variety of causes together, including a $100,000 donation by Alfy Fanjul to the Clinton Foundation.((Amy Bracken, “A Sweet Deal: The Royal Family of Cane Benefits From Political Giving.”))

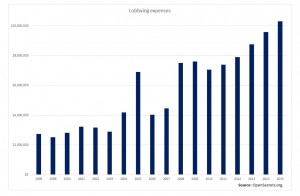

The sugar industry also spends considerable sums on lobbying. According to data from The Center for Responsive Politics, the current pace is about $10 million per year–approximately four times as much as it spent in 1998.

But money is not the only way to reward. In the 1980s, the Fanjul family expanded their growing and refining activities to the Dominican Republic: they now grow sugar canes on about 240,000 acres in the Dominican Republic and are the biggest players on the island, which is a two hours’ flight from Miami.

Apart from sugar, they are also very dominant in the country’s real estate market. Among other things, they own a 7,000-acre residential and tourism project at Casa de Campo, on the island’s southeastern tip. The project is known for its expensive homes, one of which is a $19.5 million mansion.

Casa de Campo is also where the Fanjuls have their mansion, to which they invite some of the people that they consider important–this is where they hosted the Clintons in January 2015. Other guests have included both George H.W. and George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld.

In order to support the Fanjul family by keeping the Sugar Program intact, the politicians that the family supported have had to ignore some of the family’s less glitzy aspects.

Unlike many U.S. sugar growers, the Fanjuls also import sugar–from the Dominican Republic. This puts them in a delicate position as, on one hand, they need to align themselves with local growers who are wary of imports, and, on the other hand, to take care of their interests as importers.

This duality was tested during George W. Bush’s first presidency. At the time, the U.S. promoted the creation of a free-trade zone with Central American states, including the Dominican Republic, called CAFTA-DR. In January 2012 Forbes reported that diplomatic correspondences, published by WikiLeaks, raised the suspicion that the Fanjuls had allegedly bribed Dominican politicians so they would vote against the treaty, and paid for anti-American newspaper stories and ads in the Dominican press.((Jose Lambiet, “Palm Beach Sugar Barons Accused in WikiLeaks Cables of Trying to Sabotage U.S. Trade Deal.” Forbes, January 2012.)) The treaty was eventually ratified.

The Fanjuls are also facing accusations and formal proceedings regarding pollution in Florida. The accusatio

ns center on the Everglades, the wetlands that cover much of Florida’s southern tip, where they grow most of their canes. In his 2005 book The Swamp, author Michael Grunwald describes how the Everglades were contaminated by sugar growers to the extent of threatening the area’s unique characteristics. Last July, a coalition of businesses and other entities was formed to call on the state of Florida to reclaim the Everglades and save it from sugar growers’ pollution.((Now or Neverglades Declaration))

David Guest, an attorney with the environmental law firm Earthjustice, sees the sugar industry’s business expertise as not being in growing sugar but as something else. In a September 2011 Colorado Independent story, author Virginia Chamlee writes: “Guest says that Big Sugar operates differently than most agricultural industries–trading cash in the form of campaign donations for political favors in the form of subsidies. If the companies gain enough legislative support, they can ensure that agricultural legislation is written to their specifications, keeping sugar prices and subsidies high.”((Virginia Chamlee, “How Big Sugar Gets What it Wants From Congress.” The Colorado Independent, September 2011.))

The recent media attention to the way the sugar industry tried (and probably succeeded) to influence science and policy will likely make it more difficult for sugar and beverage companies to work together behind the scenes with academics to produce industry-friendly research.

But as far as subsidies, tariffs, and corporate welfare are concerned, it might take a long time before politicians will be able to stand against the sugar industry and the formidable position of the Fanjul brothers in the political arena. The Fanjuls, it seems, have found the sweet spot of the American political economy.