In his new book Monopolized, journalist David Dayen tells the stories of individuals who have suffered at the hands of monopolists, showing the myriad ways in which monopoly power affects people’s daily lives, most of which escape an antitrust regime that is narrowly focused on consumer welfare.

Monopolized: Life in the Age of Corporate Power. By David Dayen. The New Press; 299 pages.

Labor’s share of income is falling, while income inequality, the profit share, and ownership concentration are all rising. The career pathways for Americans to transition from lower- to middle-class are disappearing. Entrepreneurship is in decline. Towns are downsizing, Main Streets are vacant, and regional disparities are growing. We are witnessing the slow death of the American dream. And these trends occurred all before the pandemic.

There are several stories that tie these secular trends together, but the most compelling narrative to emerge for the United States’ economic malaise is that concentration, coupled with exclusionary conduct by dominant firms—whether in agribusinesses or hospital networks or Big Tech titans—enhances the bargaining power of monopoly platforms over workers and suppliers. A July 2020 study by economists at the Federal Reserve Board shows how “the rise of market power of the firms in both product and labor markets over the last four decades can generate all of these secular trends.”

A more accessible and non-technical narrative comes from David Dayen, editor of the American Prospect and author of 2016’s Chain of Title. Dayen is a master storyteller, and his new book on monopolies highlights his special talents. Monopolized follows a number of other antimonopoly books, from Jonathan Tepper’s and Denise Hearn’s The Myth of Capitalism (2018) to Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness (2018) to Thomas Philippon’s The Great Reversal (2019) to Matt Stoller’s Goliath (2019), and is being published at the same time as Zephyr Teachout’s Break ’Em Up(2020). These books explain how antitrust enforcement has drifted away from the original intent of the Sherman Act, to the point that the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division now uses antitrust perversely to cement, rather than disperse, the concentration of economic power.

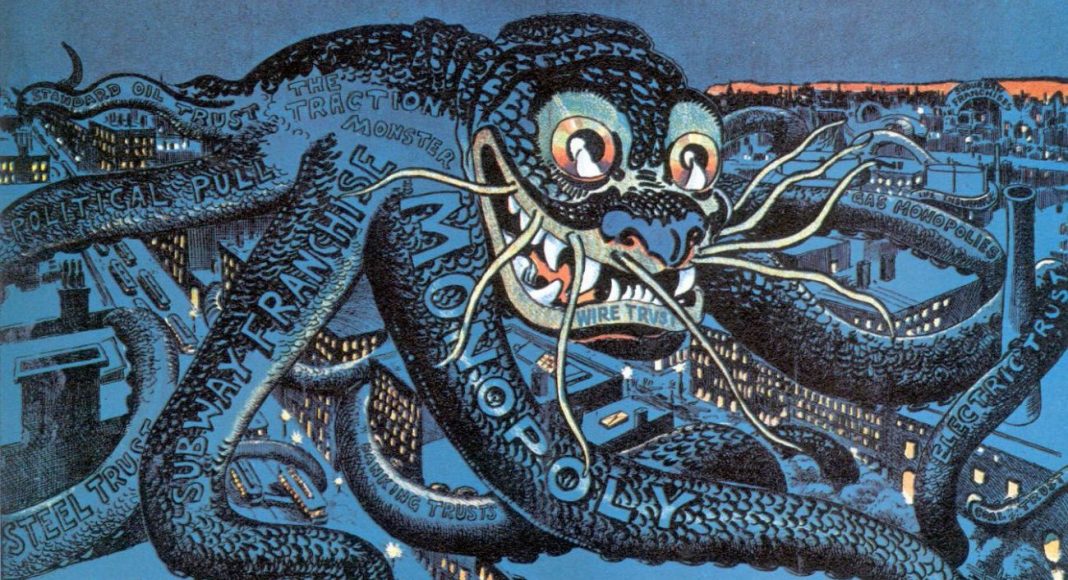

Given the resurgence of interest in reining in corporate power, culminating in last month’s Congressional hearing of Big Tech’s abuses, it feels like we’re having an antimonopoly moment.

Monopoly theory, at least told by economists, can be dry stuff. In Monopolized, Dayen eschews the sterile supply and demand charts and instead tells the gripping stories of individuals who have suffered at the hands of monopolists in their daily lives. (This reviewer made the mistake of starting the Amazon chapter one evening and couldn’t put the book down until well past his bedtime.) Dayen has a command of the economic literature and weaves in plenty of research, but the economics plays second fiddle to the real-life stories of despair at the hands of monopolists. And that’s how it should be.

Dayen argues that for every one of these monopoly abuses, there is a law that could stop it, if only it were enforced. The primary law for fighting monopoly power is antitrust. By focusing exclusively on short-run, measurable consumer harms in output markets, however, modern antitrust misses many anticompetitive harms. Dayen gives a taxonomy of such unnoticed harms, including how monopoly steals wages and depresses payments in input markets, weakens economies by discouraging edge innovation, degrades quality, heightens disasters by concentrating supply, supercharges inequality, hollows out communities, and screws up politics by creating conditions for capture.

Rejecting modern antitrust’s fixation on consumer welfare generally and short-run price effects in particular, which goes back to Judge Robert Bork’s seminal 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox, Dayen writes: “We are more than our Amazon Prime accounts. I wanted to know about monopoly’s distortion of contemporary life, what it does to our families, our jobs, and our psyche.”

Even where monopolies generate huge price effects that should trigger the consumer-welfare alarms, such as in the pharmaceutical industry, antitrust agencies largely give drug companies a free pass, intervening only in episodes of collusion. In other words, antitrust fails even under its restricted framework. Drug companies routinely take price increases whenever possible, exploiting the precarious position of patients in recognition that a few day’s worth of bad press will be swamped by the lift in share prices.

One such story that illustrates how monopolists (oligopolists, really) behave when they know customers are captive concerns the airlines. The book’s opening chapter, titled “Monopolies Are Why People Keep Contracting Deep Vein Thrombosis on Long-Haul Flights,” tells the story of Kate Hanni, who was trapped on the tarmac of an American Airlines flight for over four hours in December 2006 and launched FlyersRights.org. Due to fierce lobbying by the airline industry, the Department of Transportation didn’t implement a rule ending what Dayen calls “airline imprisonment” until December 2009, setting a maximum three-hour limit that passengers could be forced to wait on a tarmac.

Before deregulation, airlines were compelled to serve the entire nation, with popular routes subsidizing less popular routes; after deregulation, airlines cut direct routes for large portions of the country, exacerbating regional income inequality. Dayen reports that a hundred cities fell off the map in the first years after deregulation, and another 32 regional airports lost service between 2015 and 2018. At the time of deregulation in 1978, America already had the lowest fares and fares were declining, yet proponents of deregulation claimed credit for subsequent price declines. In the aughts, airlines declared bankruptcy to cut pensions and outsourced operations to non-union entities, squeezing pilots and flight attendants, a common theme of the book. The modest remaining competition that exists post-consolidation isn’t enough to force airlines to compete on basic amenities such as legroom and bathroom space.

Another chapter deals with the plight of farmers, told through the eyes of a third-generation hog farmer in Iowa named Chris Petersen. Dayen explains how agribusinesses with “industrial-sized confinement lots, ruthless livestock companies and seed merchants” have squeezed independent family farmers.

When Congress used to govern, we had protections for farmers like the Interstate Commerce Commission’s restrictions on railroad pricing; President Woodrow Wilson’s busting up the meatpacking trusts; the Capper-Volstead Act’s antitrust exemption to farm co-ops; and New Deal crop-production controls known as “price-parity” adjustments. Researchers have credited the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 with boosting farm income, which by 1935 was more than 50 percent higher than farm income during 1932.

In the absence of any protection for small farms, Dayen reports, 70 percent of hog farmers have gone out of business since the mid-1990s, and Smithfield and other agribusinesses lock family farmers into ten- to twelve-year contracts dictating the design of the barn and prices paid. Chicken farmers must compete in a “tournament system,” in which farmers are paid more or less for birds and prices are opaque.

The book spells out how the factory-farm process degrades food quality and reduces food safety—other metrics for monopoly harms that our consumer-welfare and price-fixated lens tends to miss. President Barack Obama’s Justice Department did nothing to police Big Ag, claiming (dubiously, per Dayen) that the antitrust laws made it impossible to bring a case, and Donald Trump’s team has sided aggressively with Big Ag.

“To hear Dayen tell it, the ‘middlemen have stolen all the money.’ And our antitrust laws seem incapable of policing the theft.”

Dayen’s book easily could have been called Monopsonized, but that wouldn’t have sold as well. Yet in large part, Monopolized is really about how harms to atomistic sellers (workers and input providers generally) arising from the consolidation (and exclusionary conduct) of powerful platforms have escaped antitrust scrutiny due to the misplaced fixation of regulators and courts on price effects in the output or end-user market. Farmers, for instance, keep just 15 cents of every retail food dollar, down from 37 cents in the 1980s. Perhaps relatedly, as Dayen notes, farmers commit suicides at twice the rate of veterans.

Just as farmers are squeezed by agribusinesses, news publishers are being squeezed by their own overlords—social media monopolists. News publishers chased Facebook’s whims for coveted ad dollars and eyeballs, lurching towards and then away from video, only to learn that Facebook juiced its video stats. The digital ad duopoly of Facebook and Google has “sucked up practically all the revenues from the news business, threatening the survival of dozens of independent media outlets.” Dayen reports that Facebook wanted a 30 percent cut on donations to support publishers, and Apple sought 50 percent of subscription revenue on Apple’s News+.

Sticking with the monopsony lens, with just three prescription benefit managers (PBMs) controlling 75 percent of the market, the PBM oligopoly squeezes pharmacies, charging the health plan more than they pay pharmacies in reimbursement, and skimming as much as one in five dollars out of every prescription drug purchase. Consolidation allows banks to pull out extra cash from merging companies when closing deals. Walmart’s “immiseration of workers” ironically put its low prices out of reach for many of its employees. Amazon keeps prices low by squeezing its third-party sellers. And Uber and Lyft’s ride-sharing duopoly takes approximately one-third of the fare from drivers, fighting any efforts to bring benefits or permit collective bargaining. Dayen notes that wage growth for skilled hospital workers slowed down after hospital mergers.

These seller harms have largely gone undetected by antitrust’s consumer welfare standard, which naively considers harm to sellers a good thing so long as the platform shares a portion of the underpayment (or overcharge) to the seller with the consumer.

Dayen inadvertently spells out one “benefit” of consolidation in the cigarette industry. There, the duopoly of Altria and Reynolds led to higher prices, which reduced consumption, leading to greater public health. But this only works for industries with negative externalities, like tobacco.

As the economy increasingly moves online—a transition accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic—a natural career pathway for wealth creation should include local publishers (operating on Facebook), small merchants (operating on Amazon), upstart app developers (operating on Apple), and independent content creators (operating on Google). As Dayen puts it, Amazon’s platform “should be a great leveler for startup entrepreneurs.”

But these pathways don’t exist. Last month’s House Judiciary hearing revealed how input providers are being squeezed by the dominant platforms. Merchants are flooded with counterfeits unless they buy ads from Amazon; they are disappeared from Amazon’s “Buy Box”—the section on the right-hand side of the product page that says “Add to Cart” or “Buy Now”— if they don’t buy Amazon’s fulfillment services. And merchant fees have climbed from 19 to 30 percent, which robs merchants of capturing a fair share of their marginal revenue product.

Given our laissez-faire attitude and near worship of platforms, writes Dayen, “the marketplace runs the way a big city might if all the cops left. It’s an experiment in digital Darwinism, where anything goes to muscle out the other guy.”

As Dayen makes clear, monopolies exist everywhere in our economy, including in our dysfunctional health care system. Group purchasing organizations (GPOs) buy medical supplies for hospitals, often at supracompetitive prices. Why? GPOs successfully lobbied for an exemption to the anti-kickback statutes of the Social Security Act, which allows them to erect moats around incumbent suppliers, and they’ve been nursing from the equipment-monopoly teat ever since 1987.

Even though hospitals pay more for supplies as a result of the kickbacks, many hospital CEOs have ownership in the GPOs, and are thus directly conflicted. And even the non-GPO-owning hospitals are able to pass through the inflated equipment costs to patients, insurers, and the states. In repeatedly pushing back against efforts to end the kickbacks, Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has supported the anticompetitive tactics of GPO-owning hospitals, proving that Democrats cozy up to monopoly power as well (albeit at a higher price).

It shouldn’t take a PhD in economics to understand that when a buying agent (and auctioneer for a concession) is compensated by a fixed percentage of the concession’s revenues from the winning bidder, the auctioneer will be incentivized to preserve monopoly prices and support entry barriers (See here, slide 172, for the theory, and here for empirical evidence of price effects).

But an economist has limited influence on policymaking. In contrast, Dayen’s personalized storytelling, free of any stodgy regression analysis, is more likely to move policymakers. Dayen devotes an entire chapter to these hospital-related abuses—aptly titled “Monopolies Are Why Hospitals Can Give Patients Prosthetic Limbs and Artificial Hearts but not Salt and Water in a Bag”—and gives hope that the antimonopoly battle will one day prove triumphant. He tells the GPO story through the struggles of Phil Zweig, a tireless advocate who has connected GPO practices to drug shortages, calling out GPO executives at health care conferences.

Whereas an economist would use a much less compelling phrase like “countervailing bargaining power” to describe how concentration at one level of the distribution chain (say, among hospital networks) causes concentration at another level (say, among insurance companies), Dayen coins a much more memorable term: “concentration creep.”

To hear Dayen tell it, the “middlemen have stolen all the money.” And our antitrust laws seem incapable of policing the theft. Now the question is what is Congress going to do about it. If you wish to learn about the antimonopoly movement, reading this book is a great place to start.