In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, more commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, with the goal of encouraging the production of generic drugs to increase price competition while preserving enough profit for patent-holding drug companies so that they would continue to invest in expensive R&D. In particular, it created an avenue for generic manufacturers to challenge the patents of branded drug firms (“Paragraph IV”).

While the number of generic drugs on the market did experience a dramatic increase since 1984, the act also had an unintended consequence, in the form of some cases in which the would-be generic entrants forgo their challenge and (as a consequence) delay entry—sometimes for years—in exchange for sharing monopoly profits with branded drug firms. These reverse payment settlements are commonly referred to as “pay for delay.”

Over the years, as the number of “pay for delay” settlements grew drastically, critics have argued that these deals are collusive and harm consumer welfare((Jeremy Bulow, “The Gaming of Pharmaceutical Patents,” Innovation Policy And The Economy 4 (2004): 145-187.)). The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have both declared them to be collusive and in violation of antitrust laws—in 2010, an FTC report argued that these settlements cost consumers $3.5 billion per year((“Pay-For-Delay: How Drug Company Pay-Offs Cost Consumers Billions,” a Federal Trade Commission Staff Study (2010).)). In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that while reverse payment settlements are not per se illegal, they could be in violation of antitrust law in certain circumstances and allowed the FTC to sue pharmaceutical firms on these grounds.

Are reverse settlements collusive, and what is their effect on consumers? A new study by Eric Helland from Claremont McKenna College and Seth A. Seabury from the University of Southern California finds that reverse payment settlements lead to a delay in generic entry, cause prices to inflate, and depress the quantity of competitors in the market.((Eric Helland and Seth A. Seabury, “Are Settlements in Patent Litigation Collusive? Evidence from Paragraph IV Challenges,” NBER Working Paper no. 22194 (2016).))

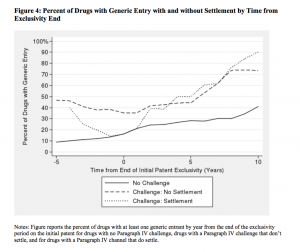

Settling Paragraph IV challenges, Helland and Seabury find, leads to an $835 million reduction in consumer surplus over 5 years after the initial challenge, with $308 million coming from lower producer surplus, and over $527 million from deadweight loss. They also find that “the immediate effect of settlements in Paragraph IV challenges is to completely offset the expected gain in generic entry from the challenge.” Paragraph IV challenges, they find, can increase the probability of generic entry by 68 percent, while settlements can delay generic entry for up to 5 years.

Previous studies have also explored the effect of out-of-court settlements on generic entry and consumer welfare. A 2004 paper by Jeremy Bulow((Bulow, “The Gaming of Pharmaceutical Patents.”)), for instance, argued that reverse payment settlements are anticompetitive and harmful to consumers. A 2013 paper by Farasat Bokhari found that the prices of ADHD drugs are 4-4.5 times higher when there’s a settlement, instead of generic entry.((Farasat Bokhari, “What Is the Price of Pay-to-Delay Deals?” Journal of Competition Law and Economics 9, no. 3 (2013): 739-753.))

The problem Helland and Seabury were trying to address with their paper, said Helland during a recent conversation with ProMarket, is that not all settlements are the same.

“The difficulty, as with anything in empirical studies involving litigation, is that the cases you observe settling are going to look systematically different. When the FTC did its study, it looked at settlements and came up with a good estimate, but the problem is that it’s an ‘orange to apples’ comparison. We are using instrumental variables to come up with a way of taking into account that the drugs involved in these settlements are really different from the average drug on the market. To do an ‘apples to apples’ comparison we need something that determines the likelihood of settlement, but isn’t related directly to characteristics of the market for the drug,” he said.

In order to account for these differences, Helland said, they relied on a U.S. Circuit Court split that preceded the 2013 Supreme Court ruling: the 2nd, 11th and Federal Circuits explicitly allowed reverse payment settlements, while the 6th and 3rd Circuits accepted the FTC’s claim that it needs to review these settlements for potential antitrust violations. Among other things, they find that manufacturers whose corporate headquarters are in areas where the courts allowed “pay for delay” settlements are more likely to settle challenges. “If your corporate headquarters is located in that district, then it’s more difficult for the FTC to bring an antitrust case against the settlement because the case is more likely to be heard in a circuit that has already ruled that settlements are per se legal. We used the location of the drug company’s headquarters as an exogenous factor making settlements more appealing to the parties” said Helland.

An expected deadweight loss of $2

1 billion over 25 years

What they found is that settlements that restrict generic entry have a significant impact on the price and quantity of drugs, which directly affects consumers. While challenging a drug patent increases consumer surplus by approximately $537 million and generic entry results in a 74 percent decrease in price, settlements reduce this gain in surplus by $470 million. For drugs “in the top quintile of a potential market,” larger branded drugs which are more likely to be challenged and are more likely to end up settling, Helland and Seabury found that reverse payment settlements reduce consumer surplus by about $2.2 billion over five years, with $815 million due to higher producer surplus and $1.4 billion due to additional deadweight loss.

A settlement on a Paragraph IV challenge, said Helland, “changes the market. There’s a big transfer of consumer surplus to producer surplus over a period of a couple of years. There’s some substitute ability to these drugs, so they’re not monopolies in the classic sense, but our evidence suggests there is at least enough market power that the parties to a settlement can delay entry and transfer some money from consumers to producers.”

Reverse settlements also have an impact on efficiency. Assuming that demand for the drugs is linear, and that the competitive price is the price post-generic entry, Helland and Seabury estimate a deadweight loss of $527 million. However, the deadweight loss could be larger, according to Helland. “If you’re selling an anti-ulcer medication and the price of your competitor doesn’t change, then you’re also not compelled to change your behavior, but our approach doesn’t capture the impact on non-generic competitors,” he said. The two suggest an expected deadweight loss of $21 billion in the next 25 years due to “pay for delay” settlements.

Overall, Helland and Seabury find evidence that at least some reverse payment settlements are collusive. That, in itself, does not mean that all “pay for delay” deals are necessarily collusive, a point to which Helland agrees. “While we do find a transfer, we certainly cannot say all settlements are collusive. But the settlements are definitely changing what the drug market would have looked like,” said Helland.

He added: “There are some good reasons why you might settle under that framework that have absolutely nothing to do with collusion. The problem is that the regulatory framework creates a way to be collusive. I don’t think the Hatch-Waxman framework envisioned the settlements. Nevertheless, the system sets up an opportunity for collusion that would not exist otherwise because no other firm can collect the duopoly rents if they challenge the patent and enter after the first challenger has reached a settlement with the incumbent. In other areas, like tech, firms would just have to fight the patent fight or not fight it. But with pharmaceuticals you can collude and Hatch-Waxman doesn’t provide a means for other potential entrants to challenge the patent once there is a settlement.”

Impact on R&D spending

Helland and Seabury also explore the potential impact “pay for delay” settlements might have on the R&D spending of branded firms. If the settlements delay the entry of generic competitors, thereby increasing the profits of branded manufacturers, then an increase in R&D should follow since firms potentially have a higher return on R&D investment.

To estimate the effect of “pay for delay” settlements on R&D, they collected data on the R&D expenditures of all companies in the Compustat North America database, particularly data on company-funded R&D that excludes government funding, but also data on employment, current value of assets, the book value of the company per share, and the reported value of plants and equipment. What they found is that firms increased their R&D spending by approximately 0.06 percent per patent in the year after the ruling. Firms who were more likely to settle their challenges increased their R&D spending by 0.05 percent in the year after the ruling and 1 percent in subsequent years. While Helland’s and Seabury’s estimate is lower than previous studies, Helland reckoned that this is a conservative estimate.

Settlements themselves, Helland stressed, don’t affect R&D directly, but only through lengthening exclusivity: if settlements are legal, a firm developing a new drug would assume that they have a longer effective exclusivity than would the same firm in a situation where settlements are not legal. “Our estimates on R&D don’t use settlements at all. They are basically using the circuit split as a way of identifying firms that have slightly longer exclusivity because they can more easily enter settlements,” he said. “Settlements only impact R&D through their effect on patent life, and wouldn’t impact the R&D of specific drugs involved in the settlement, since all the R&D for those drugs occurred years in the past and are therefore a sunk cost.”

Since the 2013 Supreme Court ruling, there has been a sharp drop in “pay for delay” settlements. Helland’s study ends before the Supreme Court decision, but he said the drop can be inferred from the paper. “The Supreme Court actually didn’t say settlements are assumed to be collusive, they put in a rule of reason. What you’re observing after the Supreme Court case is exactly what I would have predicted from the findings in our paper. Some of these settlements are going to be very difficult for companies to defend and some of the settlements would be defensible if the FTC challenged them. What the ratio of those two is, I have no idea, but what that suggests is that some of that transfer was the result of weak patents that got challenged, and companies making a deal with the generic entrant to leave them alone a little longer.”