Over the past month, option-based credit spreads spiked and remain at elevated levels. The surge signals that a recession is at our door, but its dampening over the past week suggests that the unprecedented stimulus may mitigate the blow. In the last week, the likelihood of a recession in the next 12 months has come down from 100 percent to 73 percent.

What is the probability of a recession in the next twelve months? Will government intervention curb economic carnage? The disastrous performance of financial markets over the past month, with the stock market losing over 25 percent of its value, certainly provides important clues about future growth. But sometimes stock markets are wrong, as panic selling may lead to market crashes: in October 1987, for instance, the market dropped 20 percent in a single day with no ensuing recession.

We instead turn to credit markets and look at the option-based credit spread, an index of the corporate cost of borrowing in excess of Treasuries, first constructed by Culp, Nozawa, and Veronesi.

This index exploits liquid, traded options – insurance contracts that pay off when the market declines—to compute the value of simple, benchmark corporate bonds that are unaffected by illiquidity or other market imperfections.

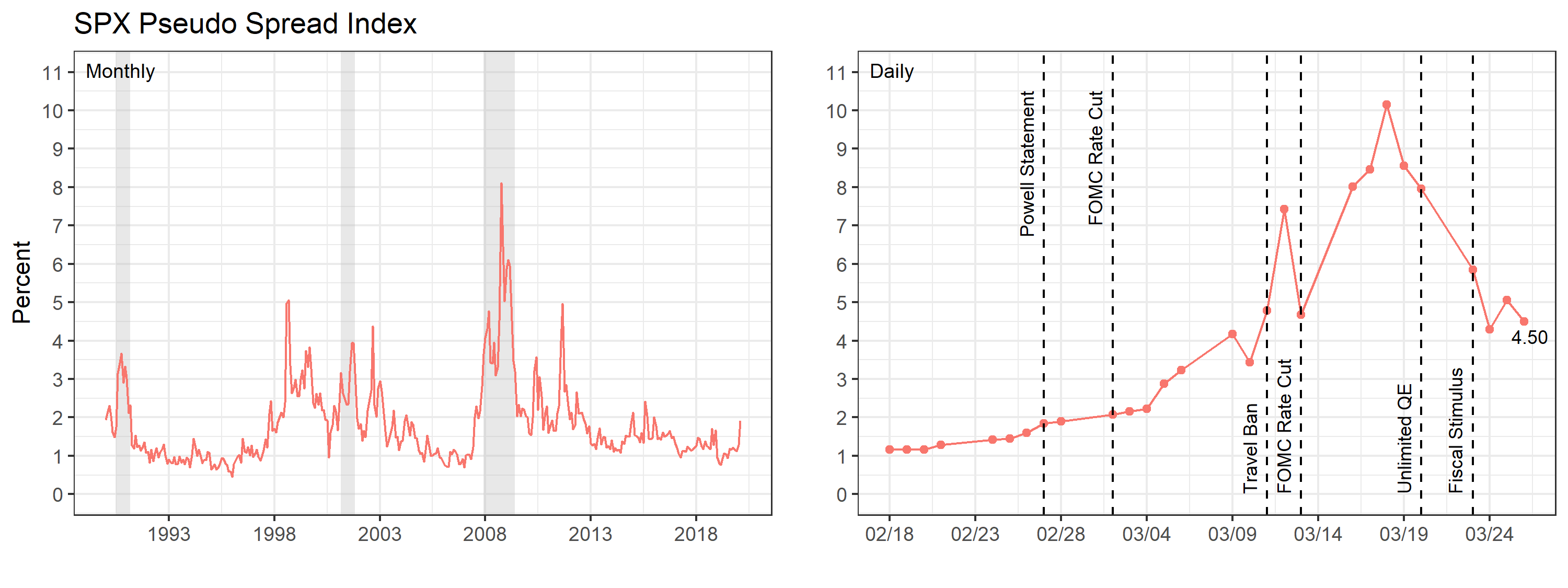

Figure 1 plots the evolution of the option-based credit spread index. On the left is the index from January 1990 to February 2020 at a monthly frequency, and on the right is the index over the last month at a daily frequency.

The widening of spreads during the 2008 global financial crisis, when the US economy tanked, is apparent. Unfortunately, the spike in credit spreads around March 18 is all too similar to that of 2008.

Interestingly, actions by the Federal Reserve in late February and early March did little to stem the rise in spreads. Spreads fell only following recent news of monetary and fiscal stimulus, down to 4.50 percent on March 26.

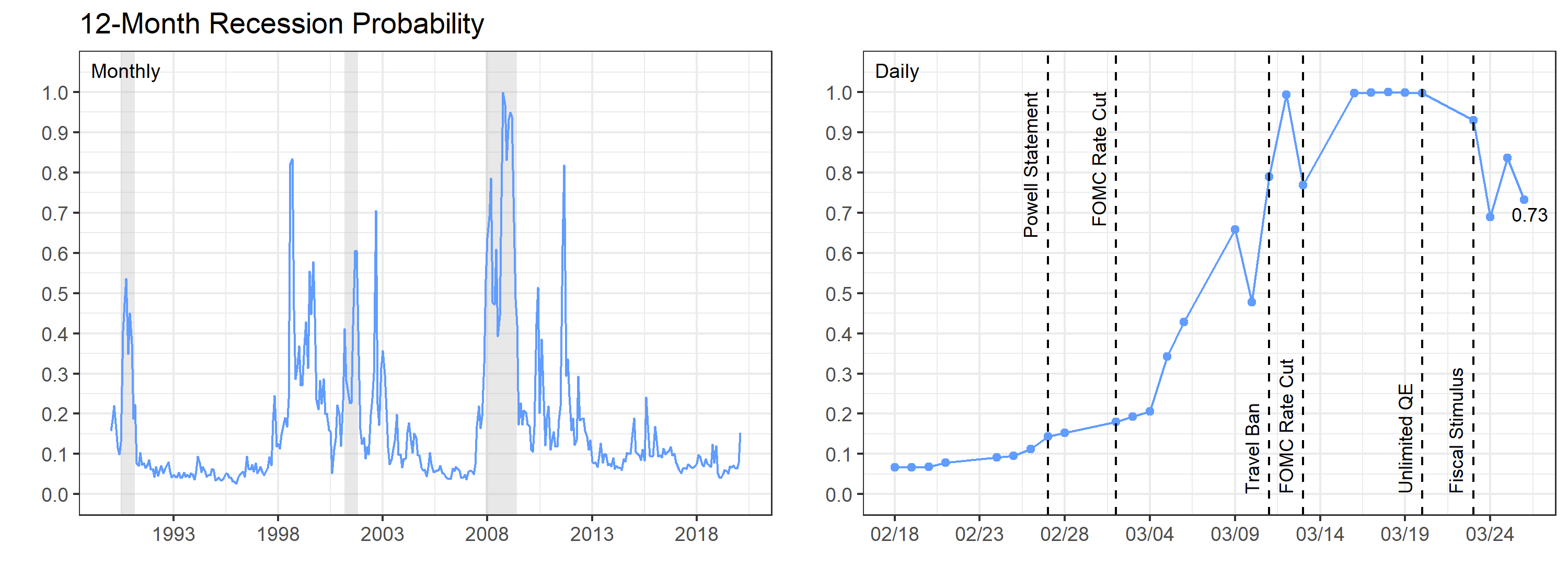

Credit spreads are important because they are among the best predictors of recessions. The left panel of Figure 2 plots the likelihood of a recession at any point over the next twelve months, from January 1990 to February 2020. The shaded regions are US recessions as dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The probability increases in recessions, and especially so in the 2008 crisis, when it hit 100 percent.

The right panel shows the same 12-month cumulative probability over the last month. Sadly, the probability again hit 100 percent on March 16, well before the announcement of shelter-in-place orders across the United States. The likelihood has come down in the last week, with the unprecedented stimulus, but remained uncomfortably high at 73 percent on March 26.

How bad will the economic damage be? The option-based credit spread index also predicts future economic activity (see Culp, Nozawa, and Veronesi).

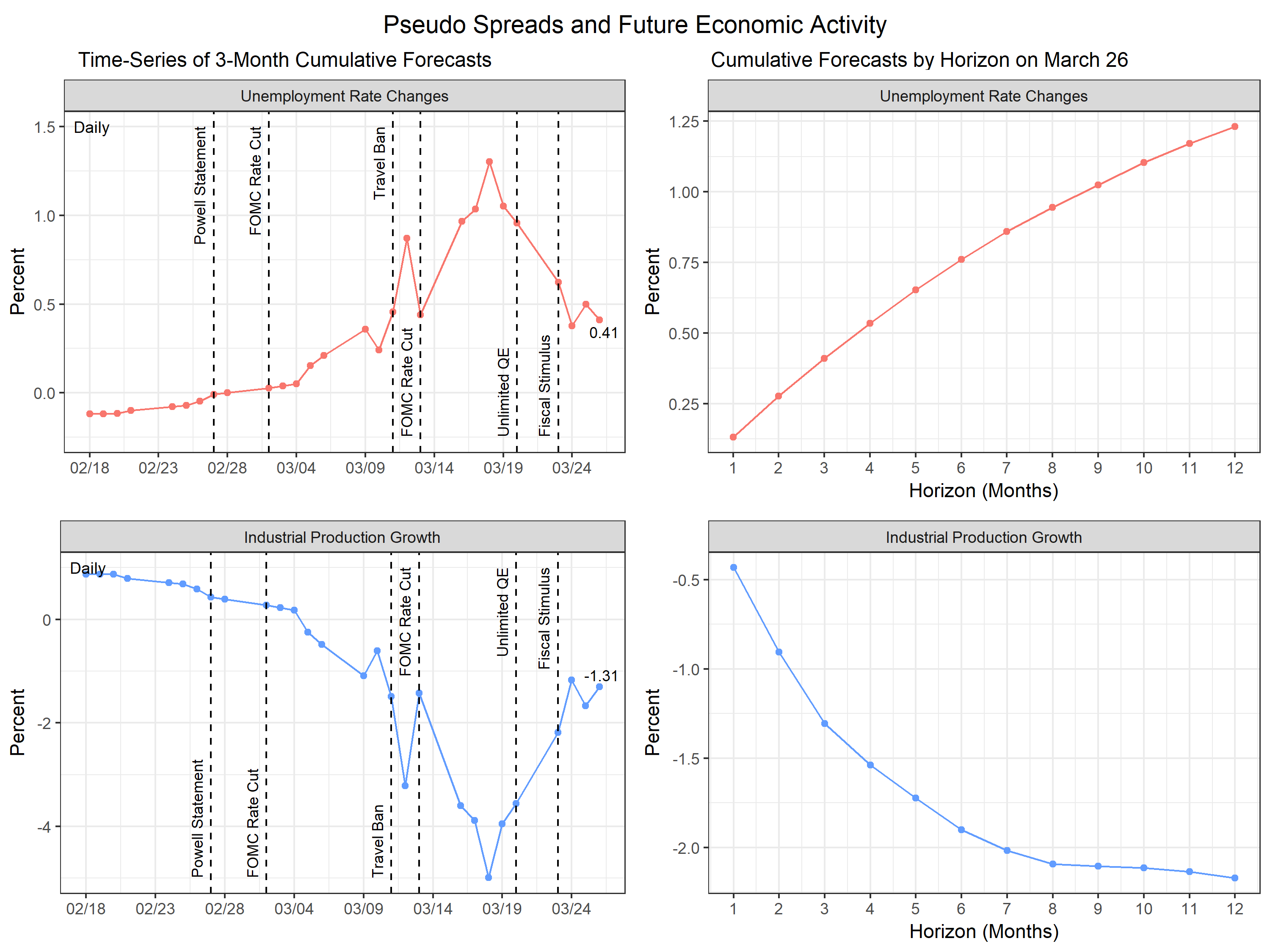

The top left panel of Figure 3 plots 3-month cumulative forecasts of unemployment over the last month at a daily frequency. Forecasts of unemployment substantially increased as the pandemic intensified, peaking at 1.25 percent on March 18.

The top right panel plots cumulative forecasts of unemployment by horizon on March 26. The stimulus did comfort markets: the index now predicts a 0.50 percent increase in unemployment over the next three months and a 1.25 percent increase over the next twelve. Relative to the 2008 global financial crisis, when the unemployment rate reached 10 percent, these forecasts are not that bad.

The bottom panel plots similar forecasts for output (industrial production) growth. Just before the stimulus, the index predicted a 5 percent output drop in just three months. After the stimulus, the index now predicts a 1.25 percent decrease in output over three months and a 2.25 percent decrease over the next twelve.

We hope that the option-based credit spread index is correct: government interventions temper the impact of the coronavirus shock, the severity of the recession, and the decrease in economic activity.

The Credit Risk Laboratory hosts the above credit spread index and a number of related series from Culp, Nozawa, and Veronesi. We update these series in real-time.

Mihir Gandhi is a doctoral student at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Pietro Veronesi is the Chicago Board of Trade Professor of Finance and Deputy Dean for Faculty at the University of Chicago Booth School Of Business.