The federal antitrust agencies don’t appear to be serious about their recent Big Tech push. And given that the Supreme Court and federal judiciary are firmly in conservative hands, it doesn’t matter—antitrust enforcement won’t come back so soon.

The occasion for this particular essay is recent news reports that some have taken as proof of the long-awaited return of American antitrust. About a month ago, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission reportedly divided responsibility between them for investigating Amazon, Google, Apple, and Facebook, and the Justice Department this week announced what appears to be yet another, somewhat different investigation of the same firms. Meanwhile, the House antitrust subcommittee has launched a Big Tech-monopoly investigation of its own.

The occasion for this particular essay is recent news reports that some have taken as proof of the long-awaited return of American antitrust. About a month ago, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission reportedly divided responsibility between them for investigating Amazon, Google, Apple, and Facebook, and the Justice Department this week announced what appears to be yet another, somewhat different investigation of the same firms. Meanwhile, the House antitrust subcommittee has launched a Big Tech-monopoly investigation of its own.

These tidbits are recent and got a lot of attention, but they are part of a longer history. While I wish it were otherwise, they probably do not portend meaningful policy changes, any more than similar events that have taken place every few weeks or months for the past several years and also received a lot of press, and likewise were followed by no significant real-world change.

In popular antitrust discussion now, the interpretation of events seems off and repeatedly over-optimistic. This is a problem, because bad predictions and misdiagnoses can cause policy dysfunction of their own.

The most important mistake has been the hope that merely finding new antitrust ideas, the right antitrust ideas, will turn things around. In fact, it’s been a major mistake to believe that what we really need is reform to antitrust law itself, in any way. Antitrust law surely has many flaws, and statutory amendments or theoretical innovations might be perfectly wonderful. But in themselves, they won’t fix what is actually wrong, and they will not meaningfully change enforcement or affect the economy. It has been frustrating to see basic barriers to any such reform ignored in so much of the antitrust talk of the past few years, and dispiriting to watch the growth of yet another would-be antitrust renewal, since it seems as likely to fail as most others have.

For five years or more, overeager journalists and pundits have been predicting that we are right on the verge of an antitrust revolution. A long op-ed by Pulitzer-winning journalist David Streitfeld, published in the New York Times a few weeks ago, was emblematic of that. Once again, it posed a narrative in which the antitrust revolution will be led by a brave band of “renegade scholars” who have discovered key intellectual mistakes in our law and economic theory. It is a hero story, banking heavily on the emotional appeal of outsider iconoclasm. Just a little more agitation, goes the narrative, a little more fearless advocacy by unlikely heroes, and the walls of Jericho will fall.

I would love to share this optimism. I long for a regime that brings back simplified rules, built around comparatively simple pre-judgments about industry structure and suspect conduct. I hope such a thing could be founded on a reasonably good-sized consensus that concentration correlates with economic injury and that the risk of under-enforcement is more significant than over-enforcement, flipping policy priorities back to where they had been for a long time. I want it all to be imposed by agency leaders with confident and fearless enthusiasm, and by private plaintiff lawyers who are no longer caricatured as venal pariahs. I’ve wanted basically nothing else for 20 years.

Yet the popular confidence is riven with misunderstandings and unrealistic expectations. Streitfeld’s opinion piece happens to be representative and timely, its enthusiasm based around several paragraphs claiming that a famous old trust-busting Supreme Court decision called Brown Shoe Co. v. United States is “enjoying a resurgence.” Brown Shoe was a long opinion and stood for a lot of things and it’s not entirely clear which of the many things it said are “resurging,” but Streitfeld seemed to imply that there will be some return of strict merger enforcement, based on prophylactic rules keyed to small concentration increases and mere “trends” toward monopoly.

| “The most important mistake has been the hope that merely finding new antitrust ideas, the right antitrust ideas, will turn things around.” |

It may seem rather in-the-weeds to harp on a mention of one old court case in one op-ed, but it isn’t. The piece was written by an eminent journalist and appeared in the nation’s most prominent news organ, and yet its argument is built around a claim that to any competent antitrust lawyer is laughably false. More importantly, it bore the same implicit misunderstanding that has misled so much of the rest of the new antitrust enthusiasm.

Absent some extraordinarily unlikely statutory amendment, Brown Shoe cannot “resurge” unless the courts want it to, and the Supreme Court above all. But we just confirmed a very conservative Justice to a majority-conservative Supreme Court who, as a lower court judge, described Brown Shoe as a “1960s-era relic”, one that he considers to have already been reversed sub silentio. It would be perfectly swell if Brown Shoe resurged, but it isn’t going to happen, in the near or medium term.

Therein lies a fundamental reason that periods of antitrust enthusiasm so often disappoint: Those who see revolution in each new news cycle tend to think that what matters in antitrust is ideas. If events indicate that we might soon replace the “consumer welfare” standard, for example, or largely repeal existing antitrust by rebuilding it around a model of collective bargaining, or whatever else, then antitrust will be righted for the foreseeable future.

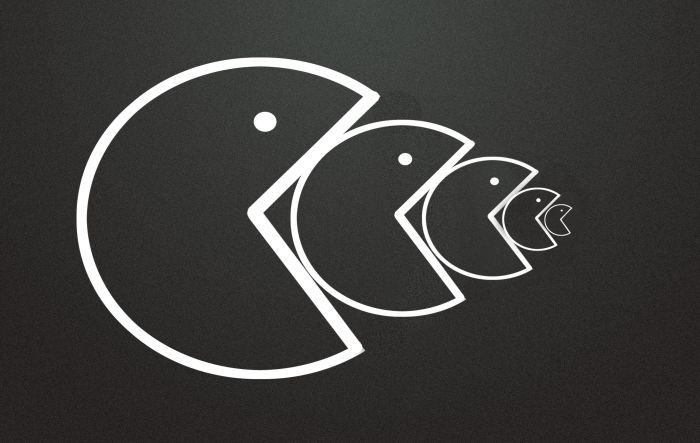

They are mistaken. Institutions are at least as important in antitrust as ideas, if not more so, and the most important antitrust institution of all is the federal judiciary. Though the policy’s failure is now widely blamed on conservative economic ideas associated with the University of Chicago, the law did not change because judges were persuaded to reconsider their pro-enforcement views. It changed because the judges themselves were replaced. Richard Nixon was able to appoint four Supreme Court Justices in the early 1970s, and a new conservative bloc quickly turned what had been the most pro-enforcement antitrust Court in American history to the most anti-enforcement.

Accordingly, the most significant antitrust mistake in recent times has not been the failure to adopt the correct ideas, but the failure to elect any Democratic President in 2016. Events could still surprise and predictions are hard, but now that Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are on the bench, with more than a year left for further Trump appointments, hopes for reverting back to the antitrust of old are largely dead, for a generation at least. Reform now requires changing institutions that are hard to change, and by and large, that will require focusing on things other than antitrust. That is to say, it requires change to the judicial personnel itself. That, in turn, seems likely to require reform of electoral institutions that at present preclude America from having a White House and Senate that could produce a Supreme Court consistent with the apparent popular desire for antimonopoly.

Is there something new or different about the events of the past several weeks? As for the antitrust agencies, who can really say for sure. For the moment, the most charitable thing one can say is that the antitrust agencies under Trump are unpredictable and that their true motives are inscrutable.

The Justice Department and its sometimes tough-talking leader brought United States v. AT&T, the first vertical merger challenge in 40 years, and many—including me—thought that it augured bigger things. But both agencies appear otherwise to have substantially underperformed in enforcement overall. For every speech in which AAG Makan Delrahim seems to talk tough and promise something new, he’s given other speeches embracing apparently strong small-government reticence and libertarian absolutism. Several of the Justice Department’s actions seem to confirm his reservations, like its initiative to end long-standing oversight of music and video licensing, its bizarre interference in the FTC’s trial of FTC v. Qualcomm, and its frequent interventions on behalf of defendants in private antitrust cases. Both agencies’ political leadership has been filled with very conservative appointees who have long railed against antitrust enforcement, in contrast with whatever their leaders might say in public appearances.

And then today, in what seems likely to be remembered as Delrahim’s most significant decision, the Justice Department approved the T-Mobile/Sprint merger, a massive 4-to-3 merger largely reprising one blocked by the Obama administration. Strikingly, the agency approved that deal in a settlement joined by five Republican state Attorneys General, even as a separate challenge by ten Democratic Attorneys General remains pending and may well block the deal outright.

Finally, even the significance of the AT&T case will remain ambiguous. We must always wonder how much it was motivated by President Trump’s own personal politics, especially since that one very unlikely challenge remains the only really significant case initiated by the administration in more than two years.

As for the fact that a House committee has opened hearings, it means very little. Congress has taken essentially no meaningful antitrust action in living memory, outside of criminal enforcement, where bipartisan carceral agreement favors continually increased penalties. Outside that context, committees hold hearings all the time. They tend to generate media attention, but then virtually nothing ever happens.

Furthermore, the current House hearings happen to expose one fault line most likely to frustrate this present season of optimism. The many advocates now urging and counting on antitrust reform harbor serious disagreements among themselves. Their goals often directly conflict with each other, and the tension will frustrate any meaningful change they may seek.

The House hearings promise to rectify “four decades of weak antitrust enforcement.” But they began not with demands for new enforcement or legislation to give enforcement back its teeth. They began with a day-long consideration of a new antitrust exemption. Subcommittee Chair David Cicilline (D-RI) held that hearing on his own bill to authorize collective bargaining between news organizations and tech platforms over ad revenue (a bill written, as one might guess, by the news organizations’ corporate lobbying arm). The plan mirrors other recent proposals that describe themselves as antitrust ideas, but would in fact largely undo antitrust by authorizing weaker parties to bargain collectively with stronger ones. However interesting or promising these ideas might seem in the abstract, they are not new and they have extremely bad track records.

As for the Cicilline bill, even aside from the practical problems and near-certain unintended consequences it poses, as well as the very broad, evidence-backed consensus that antitrust exemptions do no good and often cause harm, the news industry has already had a big antitrust exemption since 1970. It is widely considered to have failed thoroughly. It has done nothing to preserve failing papers—they’ve suffered for decades and their numbers began shrinking drastically long before the tech platforms even existed—and it has done nothing to preserve editorial diversity or journalism as an enterprise. The point is not that this particular bill is a bad idea, or that it’s a mistake to try exemptions or countervailing-power alternatives or any such thing. The point is that those alternatives are currently pushed by a vehement coalition, who’ve made clear they believe that traditional antitrust and the market-oriented approach it embodies are thorough failures. Against them, a different large coalition believes, with quite comparable vehemence, that the other coalition’s ideas are dangerously wrong and counter-productive.

So even if it is ideas that truly matter and not institutions, today’s antitrust movement cannot even agree in very significant numbers on what the right antitrust idea ought to be. Who really knows what will happen, but when even those who favor pro-enforcement reform disagree so strongly on substantive fundamentals, the building of any really meaningful political coalition seems pretty implausible.

Overall, people should be wary of what they read in the papers and particularly careful when overly optimistic predictions are based on “renegades” or disruptive mavericks, especially when those seem so at odds with the real interests of the politicians in question. It’s simply too good to be true.

Chris Sagers is the James A. Thomas Distinguished Professor of Law at Cleveland State University, and the author of ‘United States v. Apple: Competition in America,’ forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

The ProMarket blog is dedicated to discussing how competition tends to be subverted by special interests. The posts represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty. For more information, please visit ProMarket Blog Policy.