A new field experiment sheds light on why Google continues to dominate the search engine market despite regulatory interventions and the availability of alternatives. The authors find that while Google offers higher quality, consumer overestimation of this advantage—along with inattention and default effects—helps entrench its market power and limits the effectiveness of proposed antitrust remedies.

In recent years, Google has found itself in the crosshairs of regulators on both sides of the Atlantic, becoming central to one of the most consequential competition issues of the digital age. First the European Union in 2018, and then the United States in 2024, found Google violated monopoly laws in the search market.

Our new paper, “Sources of Market Power in Web Search: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” provides fresh empirical evidence that sheds light on why Google has such high market share in online search. Through a field experiment involving 2,354 U.S. desktop users, we demonstrate that Google’s market power stems from its high quality relative to competitors, but also from an overestimation of this quality gap by consumers. These forces are reinforced by inattention and default effects.

In response to the EU’s ruling, Google introduced a choice screen requiring users to decide which search engine to select as their initial default for new Android devices. In the U.S. case, the next step for the presiding judge, Amit Mehta, is to determine an effective remedy. Proposed remedies include choice screens like in the EU, or prohibiting Google from signing revenue-sharing agreements with Apple and other web browser providers to be the default search engine, among others.

Our findings have significant implications for antitrust policy and suggest that some of the discussed remedies—such as choice screens and data sharing—are unlikely to meaningfully shift market share.

Defaults and inattention as sources of market power

When estimating our model from data collected in the experiment, we found that about a third of users are inattentive—that is, they do not even think about which search engine they prefer. Of those users instructed by the study to temporarily adopt Microsoft’s Bing, 40% stayed permanently, with 44% of stayers indicating that they simply forgot to switch back. Despite this widespread inattention, a key finding of the study is that inattention has a surprisingly low impact on Bing’s market share. The low impact arises because users are frequently defaulted into the search engine which, on reflection, would have been their preferred choice anyhow: Google. Indeed, as part of the experiment we asked users to make an active choice between Google and Bing. A large majority still chose Google, with only 1.1% switching to Bing.

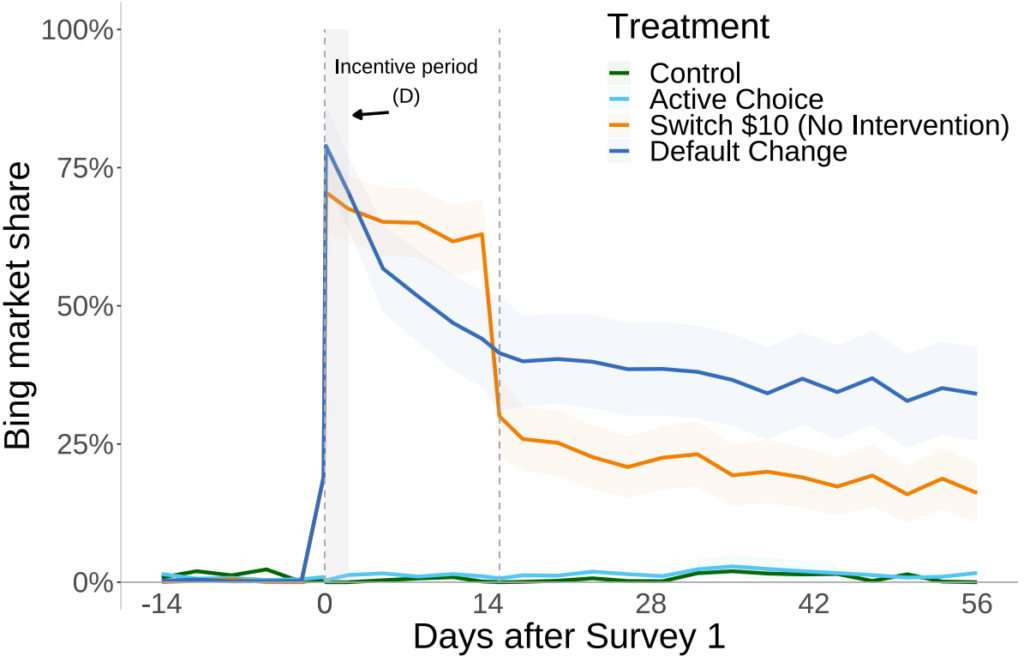

If inattention alone is not to blame for Google’s high market share, is it just that Google is a much better search engine? While we find that users strongly prefer Google, this preference weakens after exposure to its main competitor, Bing, as illustrated in the figure below. When Google users are given a choice without trying Bing, Bing’s market share increased only slightly from 0.7% to 1.1% (See the light blue line in the graph.) But when Google users experienced searching with Bing for two weeks before being given a choice, Bing’s market share jumped to a striking 22% (see the orange line in the chart). This suggests that one of the barriers to competition is lack of consumer exposure to Google’s competitors, as corroborated by our exit survey: 64% of participants who actively decided to continue using Bing reported that Bing was better than expected.

The study provides additional evidence that users misperceive Bing’s quality. We asked Google users what they thought of Bing before trying it. Their expectation was that Bing is lower quality than Google. When we gave some users a much worse version of Bing, the Google users reported Bing’s quality was only a little worse than what they expected. But when Google users tested Bing without quality degradation, they updated positively on Bing. The results indicate that learning about Bing’s true quality can alter consumer behavior.

These findings suggest why Google’s massive payments—over $26 billion per year—to secure default status on browsers and mobile devices may be effective. These defaults prevent consumers from learning about alternatives, thereby reinforcing Google’s dominant position. This is consistent with the economic theory of “experience goods,” where direct experience with a product is required to understand its quality.

Policy implications: why choice screens are not enough

Our findings have stark implications for policy. One widely discussed remedy—introducing an active choice screen when installing a browser—would likely have a limited effect. The EU’s experience with active choice screens is consistent with this. Active choice screens in the EU resulted in a less than 2 percentage points market share loss for Google. In our study, requiring Google users to make an active choice only increased Bing’s market share by 1.3 percentage points. This suggests that most users perceive Google to be higher quality than Bing and would continue using Google if presented with a choice, confirming that active choice alone does not overcome the underlying problem of misperceived quality.

By contrast, changing the default search engine away from Google could have a much larger impact. In the experiment, when users were paid to set Bing as their default search engine, Bing’s market share increased by 40 percentage points. However, this intervention comes at a significant cost to consumer welfare, reducing consumer surplus by $70.92 per year according to our model. This trade-off reflects the fact that most users prefer Google over Bing—our fitted model implies that the median user requires a payment of $3.06 to switch from Google to Bing for two weeks.

The study also challenges a common narrative about the importance of data advantages. While Google benefits from larger data sets, the paper’s findings suggest that the incremental benefit of additional search data is small. Search quality can be assessed by search results relevance, the standard measure is click-through rate (CTR). CTR measures the probability that users click on the top ranked result. According to our model, sharing Google’s search data with Bing would increase Bing’s click-through rate from 23.5% to 24.8%—a modest 5% gain that would have little effect on market share. While this part of the analysis has several important caveats, this suggests that data-sharing mandates, a commonly discussed antitrust remedy, might have limited competitive impact.

Effective remedies expose users to alternative search engines

Our results suggest that Google’s dominance depends in part on behavioral frictions and learning barriers. Most users start with Google as the default and have little reason to switch. Once they are exposed to other search engines, a significant share revise their opinions and change their behavior. This highlights the need for remedies that promote consumer learning rather than just disposing of inattention. One solution policymakers could consider is a two-part remedy: first, banning monopolists from purchasing default status on major browsers and mobile platforms, effectively giving competitors default exposure. Second—and critically—implementing a mandatory choice screen after an initial learning period. This ensures users actively select their preferred search engine after experiencing alternatives firsthand. According to our model, this two-part remedy would reduce Google’s market share by 17 percentage points without harming consumer surplus.

As with any study, our numbers should be taken with a grain of salt as some caveats apply. Our sample consisted exclusively of desktop users sourced from a survey firm—these users may not fully represent the broader population of search-engine users. Furthermore, our analysis of data sharing relies on observational data, limiting our ability to make definitive causal claims.

These caveats in mind, we believe that the key takeaway of our study is robust: the goal of competition policy should not be to force users to switch from Google to Bing, but to ensure that the search market functions as a competitive marketplace where users can make informed choices. To achieve this goal, remedies would need to address the key frictions affecting this market—lack of exposure and inattention—while respecting consumer choice. By recognizing that search engines are differentiated experience goods, remedies can effectively reshape competition without imposing significant costs on consumers.

Author disclosure: We are grateful to the Sloan Foundation, the Sloan Research Fellowship, the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), and the Business Economics and Public Policy Department at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania for generous support. We also gratefully acknowledge Microsoft Bing for sharing data with us. Microsoft did not have the right to review the paper. The experiment was approved by the MIT Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (Protocol # 2308001088) and was registered in the American Economic Association Registry for randomized control trials under trial AEARCTR-0012884; the pre-analysis plan is available from the AEA RCT Registry. Allcott, Castillo, and Musolff have previously worked at Microsoft Research. Ben Bewick has consulted on mergers & acquisitions and antitrust litigation in technology markets. Gentzkow has done litigation consulting for Google and has been a member of the Toulouse Network for Information Technology, a research group funded by Microsoft. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.