The concentration of news media has spurred concerns about their ability to protect the marketplace of ideas integral to the functioning of democracy. Based on new research, Marcel Garz and Mart Ots discuss why media consolidation may not lead to lower journalistic quality but still affects society through a decline in local news and original content.

Legacy media have struggled with declining revenues in many countries as Big Tech dominates local advertising markets. At the same time, audiences are less willing to pay for news. Traditional news organizations have responded with budget cuts, consolidation via mergers and acquisitions, and streamlining editorial activities. The concentration of media ownership and lack of funding for quality journalism raises concerns about news organizations’ ability to inform citizens and provide the kind of news that is beneficial to society and the flourishing of democracy. In new research, we study how consolidation in the Swedish newspaper industry has impacted the quality of its reporting.

Over the last decade, more than half of Sweden’s newspapers have changed ownership. According to an Herfindahl-Hirschman index of industry concentration using subscription sales, concentration in newspaper ownership increased from approximately 1,000 points in 2014 to more than 2,500 points in 2022. Competition authorities usually consider values over 1,800 points as economically problematic and a sign that shrinking competition may undermine consumer welfare, particularly price. However, in the case of the media industry, the non-economic implications of increasing concentration may be even more worrisome, as it can threaten the diversity of views to which the public has access. A robust marketplace of ideas is often considered integral to the operation of democracies.

To investigate these concerns, we collected over two million articles published by over one hundred newspapers between 2014 and 2022. Research assistants annotated a small subset of the content based on quantifiable criteria of journalistic quality, including objectivity and distinguishing between news and opinion. We then used the annotations to train large language models to evaluate how news content quality has changed since 2014 with rising concentration.

Higher quality due to economies of scale

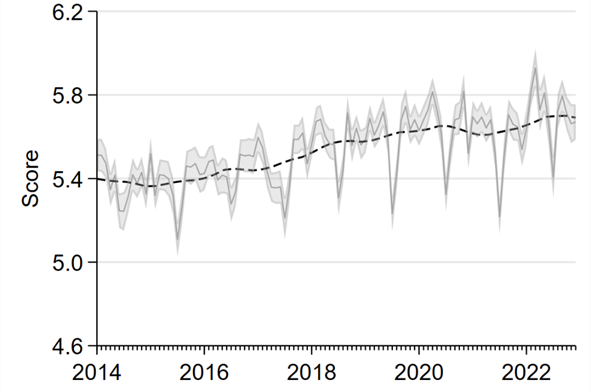

Contrary to our gloomy expectations, news quality did not decrease by our measures but slightly increased over time (Figure 1). To evaluate the role of media consolidation in this finding, we compared changes in the content of newspapers that did not participate in any mergers with newspapers that did change ownership. According to this counterfactual analysis, mergers are a key driver in improvements in news content quality. Merging newspapers often close their local editorial offices and consolidate their news production, which allows them to save costs by realizing economies of scale. Part of the cost savings are then invested in journalistic quality, such as investigative reporting, where readers are provided with deeper context and analysis and not just headline facts. For example, in a hypothetical newspaper report on a company’s layoffs, simple reporting may only report the headline figure that 20% of staff is being laid off. Deeper analysis would involve interviewing the CEO about the organizational and broader economic reasons for the layoffs as well as how labor unions were involved in the process.

Figure 1: Overall news content quality over time

More content duplication and less local news

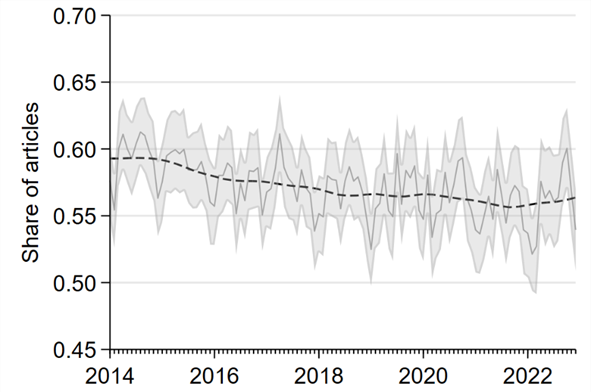

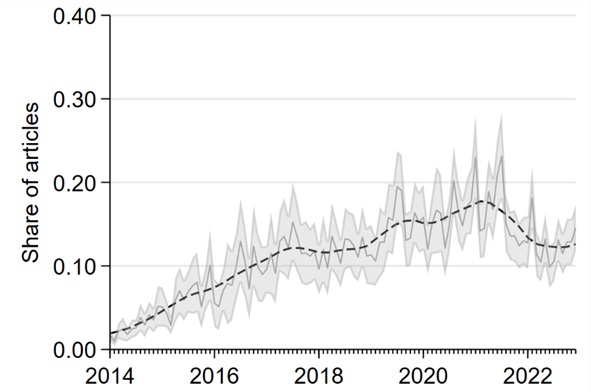

On the downside, the centralization of news production diminishes the production of local content (Figure 2). In the past, newspapers published lots of articles written by local journalists, while today they increasingly use syndicated content that is centrally produced by newspaper chains. The amount of “recycled” articles—content that is published by several or all papers belonging to the same owner—has more than quadrupled over the last ten years (Figure 3). In other words, newspapers provide less original content and content specific to a locality. Instead newspaper readers throughout Sweden consume more of the same news.

Figure 2: Local content over time

Figure 3: Content duplication over time

Are newspapers still a guardian of democracy?

While high levels of journalistic quality are good news for democracy, the increasing homogenization of content is worrisome. As newspapers provide less local news and less original content, the chances increase that local audiences do not find themselves represented in the media, which could have negative consequences for social cohesion. For instance, the rural-urban divide could grow if newspapers focus on big cities while neglecting to cover issues that are important to local news readers, such as having a bank branch or pharmacy nearby.

Similarly, content homogenization could be detrimental to political participation and accountability at the local level. As newspapers incorporate more centrally produced content, citizens may learn about events at the national or regional level but remain less informed about issues in their immediate vicinity, such as why their municipal council decided to raise the local tax rate. These citizens would remain uninformed of local politics, potentially diminishing trust in their local government. ,

It is also worrisome that smaller newspaper owners are leaving the market, while the remaining owners keep growing. The cost structure of the newspaper business, with high fixed and low variable costs, has always created incentives for them to operate on a large scale. However, the digital transformation of society has increased the pressure for legacy media to scale up and expand their activities in order to stand a chance when competing with powerful online platforms for advertisement revenue. In Sweden, the four largest chains now have a combined market share of over 80 percent. Ultimately, it is the newspaper owners who decide which news gets covered and how. The lower the number of owners controlling the market, the higher the risk of political influence.

All in all, even though newspapers still provide high levels of journalistic quality, their ability to act as the Fourth Estate is declining. Without quality local news, citizens become less engaged in local politics and less able to hold their local politicians and business leaders accountable. It also degrades a sense of community. Reinvigorating the marketplace of ideas will need to figure out how to save local journalism: democracy may depend on it.

Authors’ Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest and acknowledge funding for the underlying research from the Swedish Competition Authority (Konkurrensverket, Dnr 445/2022).

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.