In new research, Dante Donati and Hortense Fong find that the brief TikTok outage in January benefited Meta as advertisers turned to its platforms to reach users. Small businesses, less able to switch, lost out.

Critics of a potential TikTok ban have emphasized the platform’s importance as a low-cost, high-engagement marketing channel—particularly for small businesses that depend on it to reach targeted audiences. However, the loss of TikTok would not only remove a key distribution outlet for these businesses, but also have a concentrating effect on the economics of digital advertising more broadly.

In our new working paper “The Cost of Banning TikTok: Implications for Digital Advertising,” we highlight an important yet overlooked mechanism through which a ban would affect businesses: raising ad prices on TikTok’s key competing social media platforms, Instagram and Facebook.

We examine this dynamic in the short term, by leveraging a natural experiment—the temporary TikTok outage that occurred in the United States on January 19, 2025. For roughly 14 hours, the app was unavailable due to regulatory uncertainty surrounding its future. During this period, advertisers were forced to reallocate spending, and other platforms, particularly Meta’s Facebook and Instagram, absorbed the sudden shift in businesses’ demand for advertising. TikTok users also reallocated their time to other platforms. Although most TikTok services resumed by the evening of January 19, the TikTok app did not return to the Apple and Google app stores until February 14, 2025.

Using publicly available data from the Meta Ad Library covering about 30,000 advertisers, we find three key results:

- Ad prices on Meta platforms (cost per thousand ad impressions) increased by 10% following the outage, driven by intensified competition for limited ad inventory.

- Larger advertisers responded more strongly, increasing their ad spending by 66% and launching more campaigns, indicating that Meta is a better substitute for larger advertisers than for smaller ones.

- Smaller advertisers were far less able to adjust. Many who advertised on Meta during the outage reduced spending or exited altogether once TikTok resumed operations.

These findings suggest that a TikTok ban would not only increase platform concentration in an already consolidated digital advertising market and drive up ad prices, but also impose disproportionate costs on small businesses, which often lack the flexibility or expertise to pivot to alternative platforms.

The lead-up to the TikTok outage

The events leading up to the January 2025 TikTok outage were set in motion months earlier. In April 2024, President Joe Biden signed legislation requiring ByteDance, TikTok’s Chinese parent company, to sell the app to a U.S. company or face a ban in the U.S. market.

As the January 19 deadline approached, TikTok preemptively went dark on the evening of January 18, removing its app from the Google and Apple app stores and effectively shutting down U.S. access. The following day, President-elect Donald Trump announced that he would delay enforcement of the ban once in office, and TikTok gradually began restoring service. Although the app returned online that same day, it remained absent from app stores until mid-February.

What happened to ad markets when TikTok went offline?

From a theoretical standpoint, the impact of TikTok’s disappearance on ad prices was initially ambiguous. On the one hand, advertisers would reallocate their budgets to other platforms, increasing demand and putting upward pressure on prices. On the other hand, displaced TikTok users were expected to spend more time on platforms like Instagram and Facebook, expanding the available supply of ad impressions and potentially lowering prices. Ultimately, which effect dominates depends on the relative magnitude of these shifts. Adding complexity, platforms like Instagram and Facebook allocate ad inventory through real-time auctions, where advertisers bid for impressions based on targeting parameters and expected performance. Prices—measured by cost per thousand impressions (CPM)—are set dynamically in each auction.

During TikTok’s shutdown, advertising activity surged on Meta-owned platforms. The number of active advertisers, total ad spending, and volume of ads all increased sharply. Larger advertisers in particular were quick to adjust—launching 21% more ads and increasing their daily spending by more than 68%. By contrast, smaller advertisers raised their ad count by just 7% and increased spending by 26%.

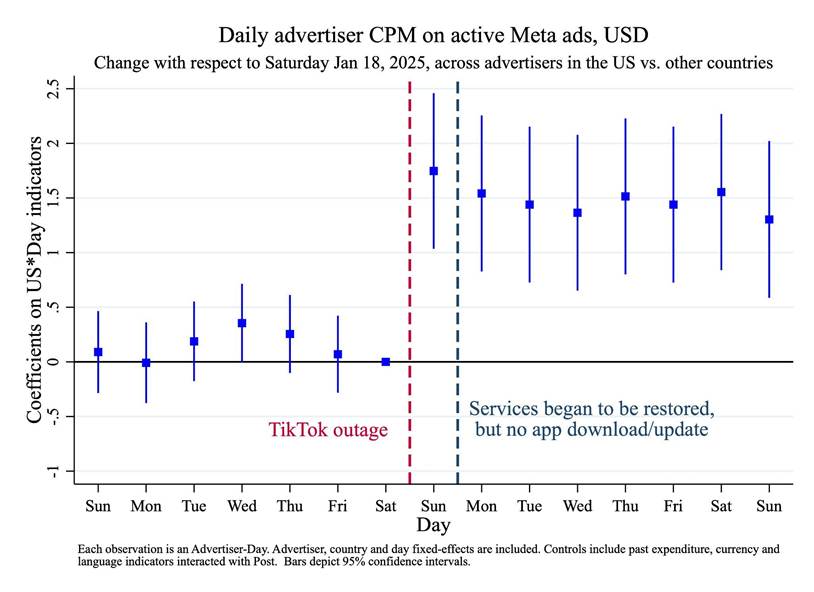

This influx of demand was not matched by a comparable rise in supply of ad inventory. While some TikTok users shifted their attention to other platforms, the number of ad impressions on Meta remained largely stable. This limited increase in available ad inventory meant that advertisers were bidding against each other for roughly the same amount of attention—driving up prices. The CPM on Meta platforms rose by 10% overnight, a sharp jump that held throughout the following week (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The disadvantage for small advertisers

Larger advertisers increased ad spend on Meta platforms significantly more than smaller advertisers, indicating a greater ability to substitute away from TikTok. This may reflect lower budget constraints, as well as greater expertise and experience managing campaigns across multiple platforms. Industry practitioners often note that TikTok is particularly valuable for budget-constrained advertisers, offering lower costs and higher engagement than Instagram. On average, TikTok’s average U.S. CPM was half of Meta’s in Q1 2024. By contrast, Instagram and Facebook provide more sophisticated targeting tools, which would benefit advertisers with more experience, technical know-how, and customer data. The fact that smaller advertisers substituted less suggests that a ban on TikTok would be more harmful to them.

The strong preference among smaller businesses for TikTok was further evident in their behavior once the app came back online. Among the advertisers that advertised on Meta during the day of the outage, smaller advertisers quickly reduced spending or exited altogether once TikTok was restored, while larger advertisers maintained their increased spending on Meta. A permanent ban would not only raise advertising costs, but also significantly limit the ability of small businesses to compete for advertisement space in the broader digital marketplace.

Policy implications and unanswered questions

The TikTok outage illustrates how seemingly targeted regulatory actions can have far-reaching and uneven effects across the economy. Even temporarily removing a major platform reshapes the advertising landscape. In this case, it shifted demand toward already dominant players, increased competition for ad space, and disproportionately disadvantaged smaller firms with fewer resources and less capacity to adapt. While large advertisers have the infrastructure to reallocate spend and optimize across platforms, small businesses are more likely to be budget constrained and have a harder time adapting to regulatory changes, which has also been shown to be the case for privacy regulation.

From a competition policy perspective, these dynamics raise important concerns. A TikTok ban would further entrench the dominance of Meta and Google—firms that already command more than 50% of digital ad revenues. It is important for policymakers to also consider downstream market consequences—especially when they interact with existing concentration in digital ecosystems. Limiting or removing TikTok—without addressing the structural imbalances elsewhere—risks tilting the digital economy further toward large incumbent businesses, and away from the smaller players who depend on diversity in platform access.

For firms that continue to advertise, higher customer acquisition costs may ultimately translate into higher prices for consumers. While this lies beyond the scope of our current analysis, it represents an important avenue for future research.

Authors’ Disclosures: The authors reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.