In a new working paper, Edoardo Peruzzi shows that under the Daubert standard for admissibility of expert witness, economists face more frequent challenges in antitrust litigation than in other legal domains, like patent or labor law. Additionally, plaintiffs’ experts are more likely to face a Daubert challenge than defendants’ experts.

The Daubert standard provides a framework of factors by which American judges can determine the admissibility and reliability of expert witness testimony. While the importance of expert testimony in antitrust cases and the influential role of the Daubert standard are widely recognized, the extent of their impact on court rulings remains somewhat unclear. In a new working paper, I present novel data to illustrate the influence of the Daubert standard in American antitrust litigation. I find that economists face more frequent Daubert challenges in antitrust cases than in other legal domains, such as patent law, and over a third fail to meet the Daubert standard. My research also shows that Daubert increasingly burdens plaintiffs, making it a critical factor in antitrust litigation today.

The Daubert standard and its significance in antitrust trials

Similar to many other jurisdictions worldwide, the United States legal system aims to prevent the use of “bad science” in litigation, and one way it does this is by giving courts the gatekeeping authority to screen and exclude expert testimony. The Supreme Court’s 1993 Daubert decision and the ensuing Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence provide the guiding rule for addressing scientific evidence in legal proceedings. The Daubert standard provides the legal basis for federal courts to assess the admissibility of expert testimony. Under this standard, judges must evaluate the methodology of expert testimonies to ensure their relevance and reliability in legal proceedings. Relevant evidence is defined as that which makes a fact more or less probable than it would be without such evidence. “Reliable” is equated to “scientific,” which, as Justice Harry Blackmun wrote, means reaching conclusions through the use of scientific method. Thus, courts should focus not on the conclusions an expert draws but exclusively on their methodology.

Economists have long entered into the courtroom as experts armed with economic theory and econometric techniques. Over the last two decades, this trend has intensified, as high-profile cases marked by battles between experts make their way onto magazine covers. In a sense, heavy reliance on experts is unavoidable in antitrust. In contrast to criminal law, where facts such as physical evidence or witness testimony often directly establish guilt or innocence, antitrust law deals with market dynamics in which facts alone, like pricing data or market share, don’t reveal whether competition has been harmed. Therefore, the use of economic theories and models for the interpretation of these facts is necessary. Economic theory also provides indispensable tools for analyzing “but-for” worlds: counterfactual scenarios that explore what might have happened in a market if certain actions or behaviors had not occurred.

However, before even taking the stand and facing cross-examination, expert economists encounter a significant hurdle: the opposing party can file a motion to exclude, asking the court to assess the admissibility of their testimony under the Daubert standard. If successful, the motion to exclude could deliver a decisive blow to both the party’s chances of winning the case and the expert’s reputation as a competent authority. The judicial assessment of the admissibility of expert testimony in antitrust cases is a significant yet frequently overlooked factor to understand the relationship between economic expertise and modern antitrust enforcement.

Empirical study of Daubert challenges

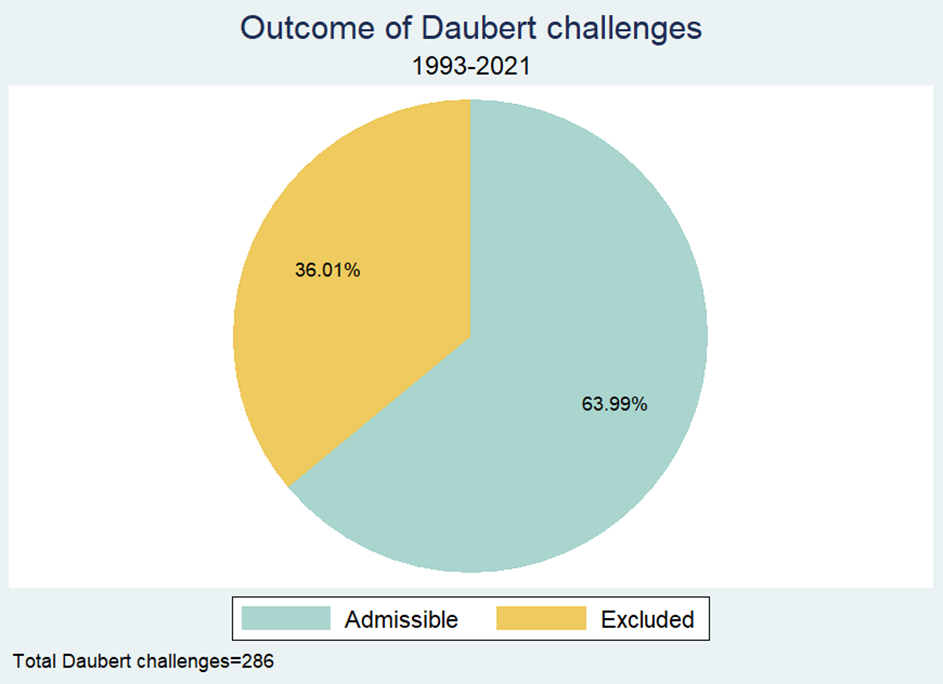

How do Daubert challenges impact antitrust enforcement? To answer this question, I isolated the gatekeeping challenges to economists in antitrust cases that can be confidently attributed to Daubert/Rule 702 and quantified the outcome of such challenges. I created a dataset of 286 Daubert challenges to economists in antitrust cases in the period between 1993 and 2021, covering more than 200 expert witnesses in 182 cases in federal courts before 174 judges.

Figure 1

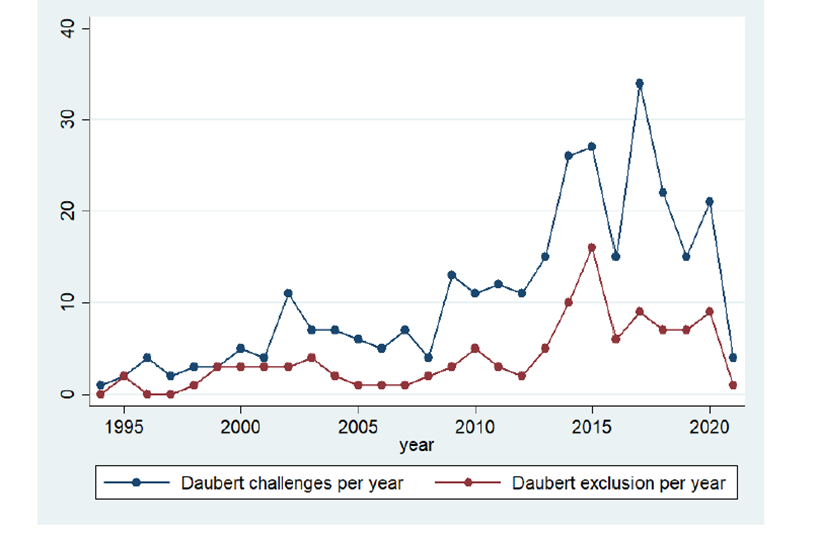

Figure 2 shows a progressive rise in both Daubert challenges and subsequent exclusion of expert testimonies, reaching a peak of 34 challenges in 2017. Interestingly, the increase in Daubert challenges cannot be explained by a proportional increase in the number of antitrust lawsuits. Rather, a more compelling rationale takes shape—namely, that the strategic employment of Daubert challenges has emerged as a prevailing practice to curtail legal disputes at an early stage. This strategic recourse has gained particular prominence within antitrust.

Figure 2

Indeed, by combining Daubert Tracker data with information from the Administrative Office of US Courts, I find that economists face a greater number of gatekeeping challenges (including Rule 403, Rule 703, and Rule 23, and others) in antitrust cases compared to other legal domains, such as patent or labor law. Amongst all gatekeeping challenges to economic experts, about 18% of them concern “Antitrust and Trade Regulation.” For comparison, “Patent, Trademark, Copyright” cases account for about 12% and “Labor & Employment” cases account for approximately 6% of all challenges. Therefore, in absolute terms, economists have received a greater number of gatekeeping challenges in antitrust cases than in other legal areas. The disproportionately high number of challenges witnessed in antitrust cases becomes all the more evident when we realize that antitrust constitutes only 0.3% of all civil cases (about 18,000 cases between 1997 and 2020), while patent law cases constitute 4% of all civil cases in the same period (about 249,000 cases). This data suggests that antitrust economists are subject to a disproportionately high rate of gatekeeping challenges in comparison to their counterparts testifying in other legal realms.

High frequency of Daubert challenges in antitrust cases

One plausible explanation for the frequent use of the Daubert standard in antitrust cases is that, compared to other legal fields, antitrust law typically requires complex economic analysis and modeling. In antitrust cases, where much of the case relies on economic evidence, attacking and potentially excluding the opposing expert could be a very rewarding tactic, if successful. Although the application of the Daubert standard can, in principle, improve the quality and clarity of economic testimony, concerns arise about the accuracy of Daubert assessment in antitrust cases. This is because Daubert often requires federal courts to make a thorough evaluation of whether economic theories and empirical methods have been rigorously applied to the specifics of a case. However, judges and juries often lack the technical expertise needed to critically assess complex economic methodologies, leading to a gap in the judicial decision-making process. Calling into question an opposing party’s expert witness can thus be an effective strategy to undermine their case.

Legal scholars, along with figures like Judge Richard Posner and Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, have long advocated for greater use of Rule 706, which allows courts to appoint neutral experts. Yet, this remains a rarity: in particular, among the 286 Daubert hearings in antitrust cases spanning three decades, a court-appointed expert was employed only twice. This reluctance likely stems from practical hurdles: selecting a truly neutral expert can be contentious, and the parties involved are often unwilling to shoulder the costs. As a result, the courts are left navigating Daubert hearings without the technical support that could enhance fairness and accuracy in dealing with complex economic arguments.

However, even if judges had greater access to neutral experts, it might not reduce the disproportionate occurrence of Daubert dismissals in antitrust cases. Fundamentally, there are two issues troubling judicial evaluation of expert economists’ testimonies. First, there’s the inherent difficulty in evaluating the methodology used by economic experts, particularly when it comes to complex statistical and econometric analyses. Second, economics differs from other scientific fields that rely on well-established, widely accepted rules—what we often call “best practices”—that guide how theories and methods are applied to specific cases. For instance, in legal cases involving DNA identification, strict guidelines must be followed to ensure accuracy, including factors like storage temperature and lighting conditions. Economics, however, lacks such widely accepted guidelines, making Daubert scrutiny especially challenging for antitrust courts.

Plaintiffs’ experts face more challenges than defendants’ experts

In addition to finding that Daubert challenges arise more frequently in antitrust cases, I also find, in line with earlier empirical research, that economic experts retained by the plaintiff are subject to significantly more challenges than those representing the defendant. Specifically, out of the 286 Daubert challenges, plaintiff’s experts were subjected to about 71% of all challenges (203 challenges). The remaining 29% were raised against the defendant’s experts (83 challenges). Amongst the challenged plaintiff’s experts, 134 were deemed admissible, and 69 were excluded. For the defendant’s experts, 49 were admitted, and 34 were excluded.

This higher frequency of challenges against plaintiff’s experts is easily explained: plaintiffs bear the burden of proof in antitrust cases, and economic analysis is critical to establishing key elements like relevant market, market power, and antitrust injury. If a plaintiff’s economic expert is excluded, their case may fail even before the trial begins. In contrast, defendants are typically focused on undermining the plaintiff’s case, a task that can in principle be achieved even without expert testimony. Consequently, defendants have a stronger incentive to raise Daubert challenges.

What is more difficult to explain, on the other hand, is the higher exclusion rate for defendant’s experts compared to plaintiff’s experts, which contrasts with earlier findings. One possible explanation could be that plaintiffs tend to raise Daubert challenges only when there is a clear and obvious deficiency in the opposing expert’s testimony. In other words, plaintiffs make more selective challenges, based on a reasonable expectation of successfully excluding the other expert. In contrast, defendants file a greater number of challenges overall, some of which are less likely to succeed, leading to a lower exclusion rate for plaintiff’s experts.

Conclusion

My paper suggests that the Daubert standard plays a crucial role in U.S. antitrust litigation, by both placing an additional burden on plaintiff’s expert witnesses and by adding pressure on judges, who must assess complex economic testimonies despite often lacking the necessary economic background.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.