Ecosystem analysis has been a popular but ill-defined concept in antitrust to identify digital products and services that operate across multiple markets. In new research, Konstantinos Stylianou and Bruno Carballa-Smichowski provide a schematic for defining ecosystems to help courts and regulators pursue more sophisticated investigations and interventions into increasingly complicated markets.

Ecosystems are here but underused in antitrust law and policy

In digital markets everything is apparently an ecosystem. Ecosystems describe market contexts where cross-market offerings, from the same or multiple companies, complement and reinforce each other’s appeal and functionality in vertical and diagonal relationships. More often than not, ecosystems gravitate around a core product. A good example is the Android ecosystem, where devices, applications, an operating system, payment services, and other services form interdependencies and interlocking value propositions. Apple offers a similar ecosystem, which despite being more controlled still relies on cross-market interdependencies to appeal to users.

In fact, one would be hard pressed to find a recent digital antitrust case or market investigation where authorities and experts did not describe the relevant economic activities, products or services as either supporting or forming part of an ecosystem: most recently Google Ad tech in the United States, and previously Microsoft gaming platform in the United Kingdom, and Google Android and Apple App Store in the European Union are all good examples.

But while “ecosystems” is becoming an increasingly popular term, it has never been used as the “area of effective competition,” meaning the arena in which authorities seek to protect competition by looking for a robust number of competitors, bad conduct, anticompetitive effects, and remedies. Instead, the area authorities usually study is a single market, such as the market for internet search services or internet browsers etc, or at most two interconnected markets, such as two-sided platforms. But this focus might need to change if ecosystems are to become a useful tool in antitrust law.

Antitrust authorities define markets and then use them as the unit of analysis to investigate which products and services are affected by potentially anticompetitive behavior. If an investigation considers passenger cars as the relevant market, Toyota cars will be included but iPhones will not. In all landmark digital ecosystem investigations this is exactly what authorities have done. Take just one example, in which the European Commission fined Apple for preventing Spotify and Apple’s other music streaming rivals from informing iPhone users that they could subscribe to their services for cheaper outside the Apple’s app store. In its investigation, the European Commission referred to Apple’s ecosystem 69 times but built its analysis on the basis of three markets: smart mobile devices, app distribution (stores), and music streaming services.

This traditional focus on markets can work well in many instances. In the Apple App Store case, the Commission was focused narrowly on anti-steering in the music streaming services market, in which Apple directed users away from using competitors’ alternative payment methods and options. In this case the market as the unit of analysis was suitable. However, there are situations, which we identify below, where relying on markets and market definition may not work for parts of the economy that are structured as ecosystems.

The problem stems from the fact that market definition as a tool was created for single, or at most two, connected markets (e.g. downstream markets, where a service, such as a software update, is provided to an end product) and it relies on substitutability, or the idea that consumers will consider products and services in this market interchangeable. Ecosystems are different in that they bring together multiple interdependent, complementary, and not hierarchically related markets. To be able to investigate the competitive dynamics within ecosystems requires a rethink of how to determine what is included in the unit of analysis and what is not.

“Ecosystem definition” instead of market definition

So far, no formal “ecosystem definition” similar to market definition has been attempted by authorities or courts. Part of the reason is that we don’t know how to do it. We know what ecosystems are, we know they are different from traditional markets, but we don’t know how to define their boundaries. As such, we are unable to say with confidence which products and services to include and exclude from an investigation.

In a new paper, we aim to do just that: we explain when ecosystem definition is desirable and we give authorities and courts the tools to define ecosystem boundaries for use in antitrust law and policy.Our proposed methodologies include factor analysis, snowball selection, network of complementarities, and also cluster analysis, which is not completely foreign to antitrust law in the form of cluster markets.

Our goal is not so much to provide step-by-step training as it is to show that there are indeed scientific ways to define ecosystem boundaries, and single out the ones we think are more useful for antitrust. Doing so will enable ecosystems to become a concrete and coherent construct in antitrust law and policy, instead of the nebulous concept it has been so far.

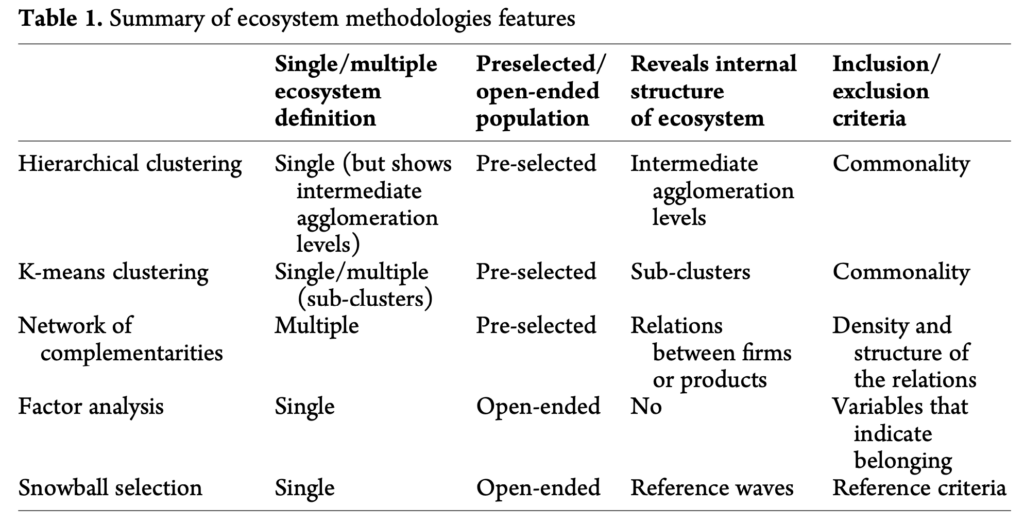

Each methodology has pros and cons for defining an ecosystem, and we make sure to highlight how they differ in terms of whether they are more suited for a single or multiple ecosystems, whether they require a preselected population (e.g. if the subjects to be studied are defined ex-ante by the investigator) or are open-ended, whether they are good for revealing the internal structure of ecosystems (e.g. which firms are more central), and what the inclusion/exclusion criteria are in the ecosystem (Table 1).

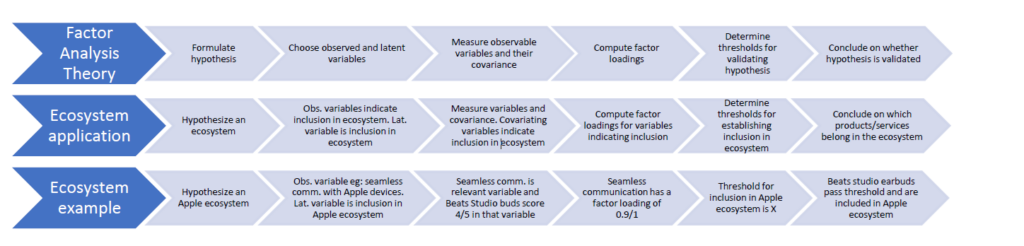

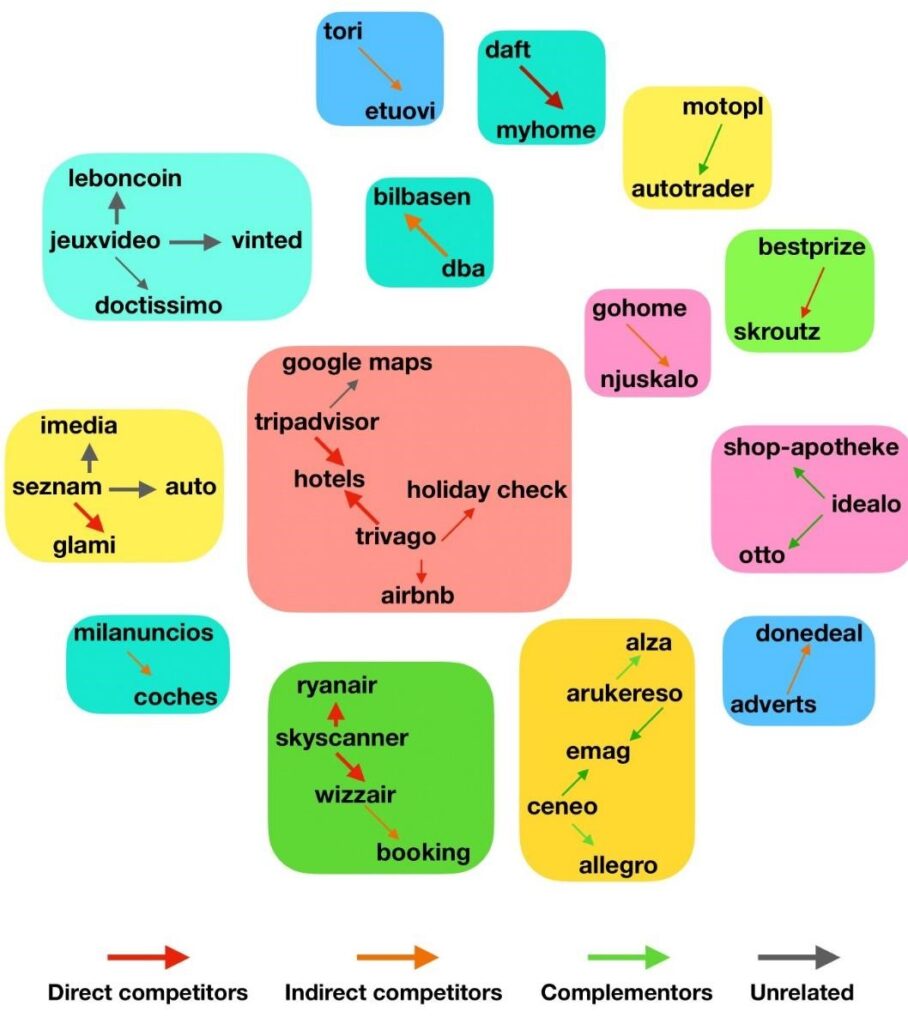

For example, factor analysis (Figure 1) may be good at identifying variables that define an ecosystem and then by measuring them determine which products/services belong in the ecosystem. On the other hand, a network of complementarities (Figure 2) approach is more useful in revealing an ecosystem’s internal structure. Take the example of the online tourism ecosystem identified at the centre of Figure 2. By using the network of complementarities method, this figure reveals that Trivago is at the centre of the ecosystem, as it is the most connected to other platforms and sends traffic to them. However, in this case, only one variable (referral traffic) is used to delineate the ecosystems. If other variables were deemed important to study the online tourism ecosystem (e.g. multihoming of consumers and business users, use of the same APIs, etc.), factor analysis could reveal which of them the data shows to be relevant to define the ecosystem.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Fig 2: The network of complementarities methodology quantifies how complementary a firm or product is to another one; based on this metric, it uses cluster analysis to group related firms/products within ecosystems. In this example, the complementarity between the main European platforms is measured using data on the referral traffic (i.e., traffic stemming from a platform-inserted link) between them, represented by arrows. The platforms in the same painted area are within the boundaries of the same ecosystem. The colour of the arrows categorizes the nature of the relation between the platforms based on their main activities: direct competitors, indirect competitors, complementors or unrelated. Source: Carballa-Smichowski et al (2021).

When formal ecosystem definition is desirable

We are not claiming that formal ecosystem definition is always required. But we do identify certain situations where, if ecosystems exist, using the ecosystem as a possible unit of analysis would enhance authorities’ work. By bringing robustness to the process, it legitimizes their actions that express concern for ecosystem-based harms.

One of these actions is market inquiries and investigations (which the U.K. recently bolstered with its Pro-Competition Intervention of the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act). If these are performed in economic segments that are dominated by ecosystems (e.g. the U.K. Competition and Markets Authority’s Mobile Ecosystems market study), then a formal ecosystem definition can help ensure that all relevant types of actors are included in the investigation, and by revealing how a selected population can be broken down into different ecosystems. It can also shed light into how ecosystems are structured internally. This, in turn, helps authorities better understand the industry, detect bottlenecks, and determine appropriate and legitimate courses of action.

A related use of a formal ecosystems definition is in the designation of Big Tech undertakings (enterprises) as having strategic market status, which in some jurisdictions like Germany and the U.K. can result in the imposition of obligations such as interoperability mandates or avoiding self-preferencing. Because such designations are usually relational, meaning that they take into account the undertaking’s cross-market positioning and activity vis-à-vis other undertakings, their mapping can often be represented as an ecosystem. Therefore, formal methodologies legitimize authorities’ designation decisions, especially given that designation decisions are subject to judicial review.

Ecosystem definition can also help assess widely discussed yet rarely addressed claims about the harms and efficiencies of conglomerate mergers that involve (digital) ecosystems. A more rigorous delimitation of which product markets are to be considered within the ecosystem can allow better detection of which markets the merged entity may have incentives to engage in anticompetitive practices post-merger, or in practices benefiting consumers. Sometimes, it can even help quantify these incentives too. When the conglomerate merger might result in the elimination of a complementor before it becomes a competitor, ecosystem definition can also give authorities a more precise vision of the potential competition the merger could eliminate.

Lastly, determining ecosystem boundaries enhances the process of calculation of fines and quantification of harm/effects. The determination of appropriate fines is related, among others, to the value of an undertaking’s sales affected by the infringing behavior, directly or indirectly. To ensure the legitimacy of imposed fines and that fines withstand judicial review in more complex ecosystem activities, the footprint of the potentially infringing behavior will have to be mapped more accurately. Without evidence of which products and services are affected by the infringing conduct, i.e. a provable causal link of how the conduct is connected to the products and services, the calculation of fines will justifiably be exposed to appeal. Formal methodologies of defining ecosystems can help to draw not only boundaries that delimit the products and services to be included, but can also reveal the internal structure of ecosystems, such that it becomes apparent how closely the generated revenue is to the infringing behavior.

Overall, we are not suggesting that market definition is obsolete (this argument has been well made by others already), nor that the concept of ecosystems should bulldoze over traditional concepts of antitrust analysis. But when an economic segment is better studied as an ecosystem, we should have the tools to determine where that ecosystem begins and ends.

Author note: Bruno Carballa-Smichowski is a Research Officer at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. This article represents his personal views and not the positions of the European Commission.

Author Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest. Read ProMarket’s disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.