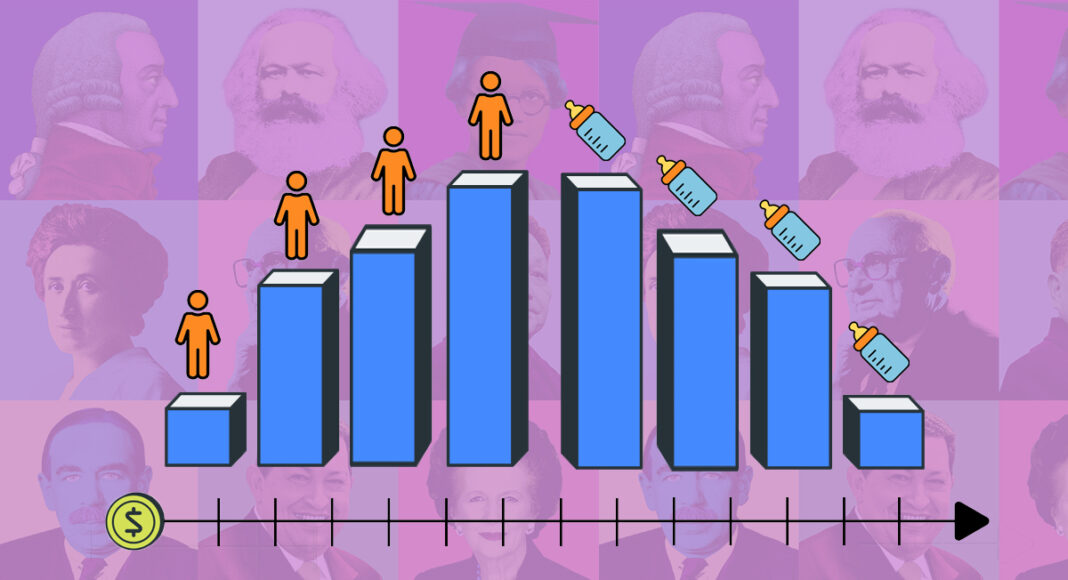

Stigler Center Assistant Director of Programs Matthew Lucky traces the history of ideas about population growth and its relation to welfare from Malthusian concerns of a population bomb to contemporary studies correlating declining birth rates in developed countries with increased investments in human capital and GDP per capita. Scholars now debate what it means for a society to have populations that do not simply stop growing, but rapidly shrink.

This article is being published in coordination with the release of today’s Capitalisn’t episode with Sir Niall Ferguson. See here for his discussion with hosts Bethany McLean and Luigi Zingales about why he worries about the social and economic consequences of a shrinking population.

The study of the relationship between population and economic growth gained traction in the late-18th century with the publication of Thomas Malthus’ work predicting that population growth would lead to increased poverty. Malthus’ hypothesis failed to predict future trends, but scholars have since struggled to understand what changes in birth rates and population growth mean for society. This article will first survey the history of these ideas before reviewing contemporary debates and concerns.

Malthus and Marx

In his famous 1798 work “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” English economist Thomas Malthus held that populations grow faster than their ability to produce food. If we assume an initial condition of “easy support,” wherein the means of food production are sufficient to a population’s current requirements, then that population is predicted to grow until “the food therefore which before supported seven millions must now be divided among seven millions and a half or eight millions. The poor consequently must live much worse.” The problem here is not that we can never increase food production, but that unconstrained fertility outpaces those improvements, leaving us perennially trapped with more mouths to feed than meals to go around. During this “season of distress,” poverty will constrain fertility. This interval of suppressed fertility allows the means of food production to catch up to the demands of the population, such that “the situation of the laborer being then again tolerably comfortable, the restraints to population [growth] are in some degree loosened.” Finally, this return to unrestrained fertility leads population growth to once again outpace food production, hence causing this cycle to repeat. In sum, Malthus provides a model of feedback loops between fertility and food production that inhibit progress in living standards.

In the first volume of his magnum opus, Capital, Karl Marx contests Malthus’ pessimistic fertility model. He argues that the “extra” people whom Malthus worried would diminish the resources available for the total population was not a corrective byproduct of growth that would keep growth in check but actually the engine of capitalist growth. Marx wrote in 1867, a time when England had undergone industrialization and moved beyond the agrarian economy of Malthus’ England, that “a surplus population of workers is a necessary product of accumulation or of the development of wealth on a capitalist basis…[the surplus population] forms a disposable industrial reserve army.” According to Marx, capitalism, through labor-saving machinery and increasingly sophisticated production methods, produces a mass of unemployed workers who exist as that “industrial reserve army.” That reserve army pushes down wages and stands ready to enroll in new capitalist enterprises. Hence, the unemployed masses are a consequence of capitalism and technological change, rather than merely overactive fertility. Furthermore, the unemployed masses are a fillip to capital accumulation and thus economic growth. For Marx, the concern about these “extra” persons was not that they would drag down the rest of society but that these extra people suffered due to the capitalist relations of production that required a mass of unemployed people to benefit the bourgeois factory owners. This concern over superfluous people, in either Malthus’s or Marx’s formulation, carried over into 20th-century thought.

Malthus in the 20th century

Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 The Population Bomb (in)famously reinvigorated Mathus’ worries about catastrophic population growth outstripping Earth’s carrying capacity. Ehrlich advised that the United States should impose a system of tax incentives to encourage smaller families and voluntary sterilization. At the international level, he recommended a strategy of global triage to determine which countries might be saved with aid and population controls and which countries must lamentably be sacrificed, in Ehrlich’s prediction, to inevitable mass famine, death, and likely cannibalism. The Population Bomb was illustrative of the intellectual milieu of the mid-20th century that produced international policy efforts to constrain population growth characterized by, for instance, sterilization campaigns in the developing world and China’s one-child policy.

Ehrlich’s work is remembered as the standard-bearer of neo-Malthusianism, but Milton Friedman had already echoed in 1946 a Malthusian assessment when discussing international aid to developing nations, saying, “we may simply give a basis for increased population growth in those countries, if we do nothing to create institutions unfavorable to population growth. In the long-run, gifts and grants may have the effect of simply impoverishing all.” For Friedman, the conditions that would inhibit population growth lacking in developing countries included industrialized urban economies and high literacy rates. Speaking later in 1977, Friedman added that while “[Malthusian concerns were] very real in some parts of the world,” by the 1970s the declining fertility rates in wealthy nations, including the U.S., rendered domestic worries moot. He was then critical of the idea that the state should intervene either to increase or decrease fertility. In his estimation, leaving families to self-regulate their reproduction independent of state interventions would result in an optimal population size.

A decade later, Friedrich Hayek wrote in his 1988 book The Fatal Conceit that “the modern idea that population growth threatens worldwide pauperization is simply a mistake. It is largely a consequence of oversimplifying the Malthusian theory of population.” To wit, Maltus’ observations are historically bounded and subsequent technological and economic advancements have rendered Malthus, and by extension his 20th-century kin, irrelevant. Indeed, Hayek takes population growth as an indicator of a virtuous cycle where population growth leads to greater economic growth producing further population increases.

Explaining the Demographic Transition

Quantity vs quality

Humanity began a series of demographic transitions in the 20th century starting in Western developed nations. Specifically, those demographic transitions entailed 1) increasing life spans (in the U.S. they have grown from 67 years in 1950 to 78 in 2020) accompanied by 2) a subsequent decline in birth rates (in the U.S., they have fallen from 3.65 per woman in 1960 to 1.66 in 2022). This demographic transition has sparked among economists a reversal in concerns from the consequences of a population bomb toward economic worries about a future defined by steep global population decline.

However, the economic consequences of declining birth rates are far from clear. This demographic transition has inverted the historical pattern linking fertility and economic growth. As Adam Smith wrote in 1776 in Wealth of Nations, “[t]he most decisive mark of the prosperity of any country is the increase of the number of its inhabitants.” Increased production and higher fertility were previously taken as correlated. Now declining fertility rates correlate with rises in GDP and GDP per capita.

In 1960, Gary Becker theorized that children could be interpreted as a luxury consumer good in developed nations, rather than, say, an input for farm output. Thus, in that context increases in demand for children began to manifest as larger investments in the “quality” (e.g. education) of a smaller set of children, rather than investing less, per capita, in a larger quantity of children.

Becker would later argue that as the stock of human capital (i.e. skills or knowledge of a worker) increases, so do the returns on investing in human capital. “This leads to multiple steady states: an undeveloped steady state with little human capital and low rates of return on investments in human capital, and a developed steady state with much higher rates of return and a large and perhaps growing stock of human capital.” Hence, in a developed economy where it pays to invest in the quality of your children, parents prioritize greater investments in fewer younglings.

Plenty of scholarship has since bolstered Becker’s theories. In 1982, John Caldwell suggested that in traditional societies, children throughout their lifetimes contribute more to their parents’ economic well-being, and thus there is an incentive toward larger families. In modern societies, that wealth flow inverts, with parents contributing more resources to their children, and hence there is an incentive structure favoring lower fertility.

More recently, a 2022 paper from Matthias Doepke, Anne Hannusch, Fabian Kindermann, and Michèle Tertilt noted “in the U.S., a trend towards educating children started particularly early, and coincided with a decline in fertility. Such patterns support the idea of a quantity-quality tradeoff.” As Oded Galor recounts in The Journey of Humanity, technological progress in the Industrial Revolution, for instance in the British cotton industry, automated away many of the simple tasks best suited to unskilled child labor, while alongside that trend was a rise in “occupations in manufacturing, trade and services [that] now required the abilities to read and write, perform basic arithmetic operations, and conduct a range of mechanical skills.” The net effect of those trends was that the labor market demand for unskilled child labor decreased alongside a rise in demand for more highly educated people (“higher quality” children) in the 20th century. Parents, then, responded by adopting family-planning strategies to meet that demand.

Women’s labor force participation

There is also ample literature linking fertility rates with women’s labor force participation and the attendant technological, cultural, and legal changes. In the same aforementioned paper, Doepke et al. propose that child-rearing is incredibly time-intensive and that women face significant opportunity costs between education/employment and parenting. Further, as the gender wage gap narrows, the opportunity costs of labor in the market versus in the household become steeper. In a 2002 study, Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz took advantage of the uneven rollout of access to oral contraceptives in the U.S. to demonstrate their impact on women’s decisions concerning marriage, family formation, education, and employment. They found that young women gaining legal access to oral contraceptives “increase[d] in the age at first marriage and also led to an increase in the fraction of women entering professional school and ending up in professional careers [law and medicine].” Put simply, when women are afforded the capacity to plan family formation, they are more likely to invest in their human capital and careers. Similarly, Martha Bailey showed in 2013 that parental access to contraception pays long-term benefits to their children in terms of educational attainment, workforce participation, and income. That is, the ability of a parent to plan their families is also correlated with greater investments in the quality of those children. In additional work, and Martha J. Bailey, Brad Hershbein, and Amalia R. Miller (2012) and Goldin (2014) have shown that the persistence of gender pay gaps within many professions can be attributed to the penalties mothers face through choosing between competing career and parenting requirements. A throughline that emerges in this body of research is that work today is not configured to be compatible with parenting.

The Consequences of Declining Fertility

Within the uneven movement of the demographic transition, David Bloom, David Canning, and Jaypee Sevilla identified in a 2003 Rand report a window of opportunity for a nation to realize a “demographic dividend” from a declining birthrate before sliding into an economically regressive aging and shrinking population. The authors contend that the initial decline in mortality rates (especially among the young), followed by a later declining fertility, creates a temporary generational bulge when a disproportionately large share of the population will be in their prime working years supporting a disproportionately smaller retired generation. Societies that invest early in education and infrastructure can accordingly exploit the generational dividend for rapid economic growth, which the authors cite was an ingredient in the success of the Asia Tigers.

Once the window of opportunity for the demographic dividend passes, we are in the realm of declining populations and fertility. The economic consequences of this change in fertility are contested. Sir Niall Ferguson has raised alarm bells about global population decline, noting that we should anticipate a future of “low economic growth, empty schools, crowded retirement homes, [and] a general lack of youthful vitality” as people currently in their prime working years age out of the workforce and ever smaller generations replace them in the economy. In the long run, Ferguson muses, humanity appears to be choosing extinction. Charles Jones, in like fashion, argued in a 2022 paper that a declining population will hinder innovation as fewer people translates into fewer new ideas. Hence, technoscience may not save us from the “Empty Planet” future, in his terminology, because a shrinking population will produce fewer innovations and be less capable of marshaling extant reserves of scientific knowledge for problem-solving.

Not everyone is pessimistic about declining birth rates or populations. In his 2022 book The Journey of Humanity, Oded Galor argues that the Industrial Revolution broke humanity free from the Malthusian world by allowing for the quantity-quality transition in childrearing and the concomitant rise in living standards. Hence, declining fertility is a necessary condition for material flourishing. He adds, “the power of innovation accompanied by fertility decline may carry the inherent potential to reduce the trade-off between economic growth and environmental preservation.” More precisely, Galor cites data suggesting that a population of 50 million with incomes of $10,000 emits far more carbon than a population of 10 million with incomes of $50,000. Thus, shrinking populations can potentially reconcile high material living standards with combating climate change.

Finally, Jennifer Scuibba notes that traditional economic theories and metrics were developed under conditions of growing populations. Robust GDP growth in a developed economy should range on average between 2-3%. But if the overall population is declining, then GDP per capita and individual economic welfare can increase even with less or shrinking growth.

So, our ideas have come full circle. Malthus feared population growth would make everyone worse off, and subsequent population declines would make everyone better off again. Only the future can tell if population declines will be a net boon to individual welfare or the source of social demise.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.