In a survey of nearly 400 European firms that export abroad, Elena Argentesi, Livia De Simone, Stephan Paetz, Vincenzo Scrutinio find that most firms believe that competition forces them to produce cheaper and higher quality products and services, allowing them to be more competitive in foreign markets.

Exports from the European Union are substantial, representing on average 15% of total member state GDP. Competition within EU domestic markets can affect exports at two stages: in the firms’ own market and in the upstream markets where the firms purchase their inputs. The economic literature is unanimous in pointing out that effective competition in domestic, upstream input markets lowers prices and boosts the quality of input goods and services. This in turn allows EU-based exporting firms that use these inputs to offer cheaper, higher-quality products, and thus be more competitive in international markets.

However, the benefits to these exporting firms from competition within their domestic markets is less clear. Most scholars argue that firms which face effective competition at home will strive to be more efficient, to make their offerings more attractive to customers through innovation and product differentiation, and will thus be better equipped when competing against their international rivals. Michael Porter is amongst the strongest supporters of this view. He holds that a nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industries to innovate and upgrade, and that companies benefit from effective competition in their domestic market, as this challenging environment forces them to innovate, which, in turn, gives them an advantage compared to international competitors.

Some authors, however, suggest instead that a second mechanism prevails, going in the opposite direction. They argue that more competition in the domestic market may be detrimental to exports, since it prevents firms from reaching the scale that would enable them to compete effectively in international markets. These contributions advocate for government intervention to incentivize the creation of “national export champions,” even at the expense of effective merger control.

New evidence on the role of competition

To untangle the net effect of domestic competition for exporting firms, we carried out a survey of European exporting firms that are active in leading export sectors for the EU Directorate-General for Competition. Leading export sectors are defined based on a criterion that considers both the absolute amount of exports outside the EU and the share of exports by the country in the worldwide export market. The leading export sectors identified in the study are: Animal products, Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals, Clothing and accessories, Foodstuffs, Machinery/Electrical, Metal, stone and mineral products, Transportation, Vegetable products, and Wood & Wood products, and Miscellaneous.

The survey involved 11 member states and was completed by 398 firms drawn from a random sample who operate in the leading export sectors. The sample of respondents mainly comprised small firms and mid-caps, consistent with Hermann Simon, who stresses that successful exporters are not necessarily large firms. Ninety-eight percent of the sample firms are more than ten years old and 57% export to more than 5 non-EU countries.

Three main findings emerge from the survey, as detailed below.

The importance of competitive input markets

The first finding confirms that well-functioning input markets are a key element of an ecosystem that enhances the export performance of European firms. Indeed, competition in upstream markets, particularly for goods, is perceived as one of the main determinants of export success. Eighty percent of respondents believe that competition in physical input markets is important for export success, compared to 67% who think that competition is important in both markets for services and their own product markets.

We broke down the answers to this question by the perceived level of market concentration (defined based on the perceived number of domestic competitors, i.e. “0-3”, “4-10” and “10+”). Results show that the percentage of firms that think that competition in input services markets and in the market for their own product is important for export success decreases as the concentration of their domestic market increases. However, the percentage of respondents that think that competition in physical input markets is important does not depend on the perceived level of concentration in their own product market: it is very high throughout all the groups of firms (about 80%). It should also be noted that the overwhelming majority of respondents (84%) procure their main inputs within the EU, which confirms that domestic competition in upstream markets can have substantial effects for our respondents.

Competition in the own market positively affects exports

The second key finding is that domestic competition in a firm’s own product market is perceived to have a relevant and positive impact on export performance. As anticipated, and according to the literature, on the one hand, domestic competition can positively affect exports by pushing firms to be more efficient, to improve product quality, and to innovate. On the other hand, competition may prevent firms from reaching a sufficient scale to be competitive in foreign markets. The relevance of these different channels was identified by using both closed- and open-answer questions. The large majority of respondents reported that domestic competition has a positive impact on company performance. In particular:

- 85% of respondents said that domestic competition incentivizes firms to improve or maintain product quality;

- 84% said it incentivizes firms to increase efficiency;

- 78% reported that it increased innovation at the company; and

- The majority of respondents disagreed with the statement that competition is detrimental for their performance, and, in fact, 66% of respondents said that domestic competition does not curb their size in a way that harms their export competitiveness.

These opinions were largely confirmed by the answers to an open-ended follow-up question, which indicated that competition had the virtue of improving firms’ quality and fostering innovation.

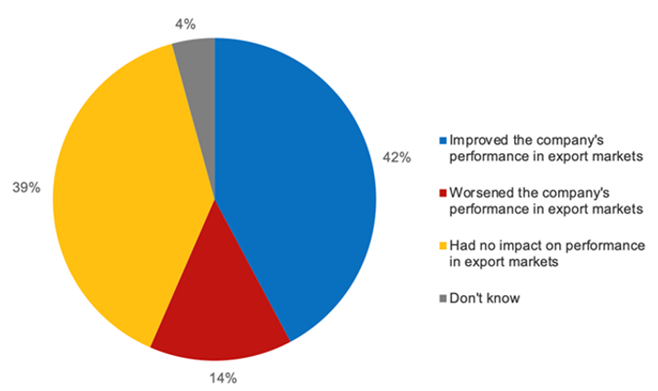

When asked more generally about the impact that domestic competition had on export performance, 42% of respondents said that it improved the company’s performance in export markets, 14% that it worsened the company’s export performance, 39% that it had no impact on the performance in export markets, and 4% did not know. Among the majority of respondents who think that competition has an impact on export success (56%), those who perceive a positive impact (42%) are therefore three times as many as those who perceive a negative effect (14%).

Figure 1: Effect of competitive pressure on performance in export markets

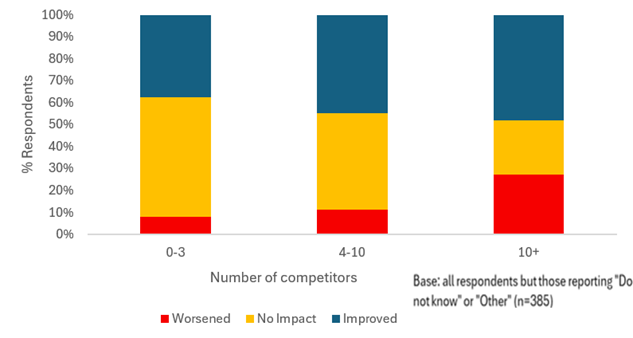

Firms’ opinions tend to diverge and to become more polarized in markets where competition is perceived to be stronger. Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, in markets with many competitors, more firms believe that competition impacts performance in export markets, both positively or negatively. There may be a good explanation for these seemingly contradictory views. Competition selects winners and losers. It is not surprising that the latter group believe that the intensity of competition is responsible for their failure in entering foreign markets, while the former recognizes that the incentives they face in the domestic market lead them to perform well enough to win the competition abroad as well. Instead, in more concentrated markets, where competition is likely less intense, the proportion of respondents who believe that competition has either improved or harmed export performance is smaller. In other words, they don’t perceive competition in the domestic market as having much effect on their performance in the export market.

Figure 2: Effect of competitive pressure on performance in export markets, by perceived number of competitors in the domestic market

The importance of product quality

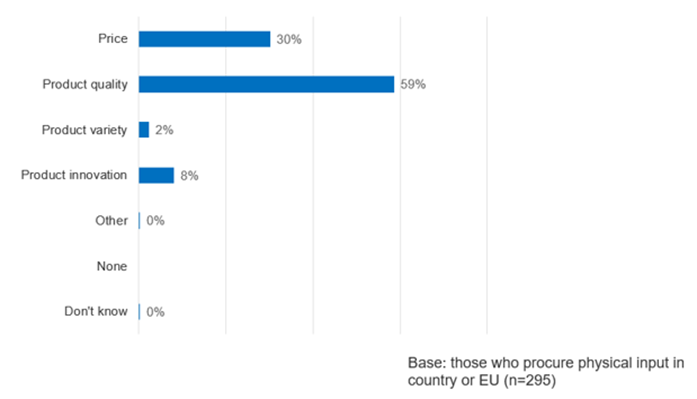

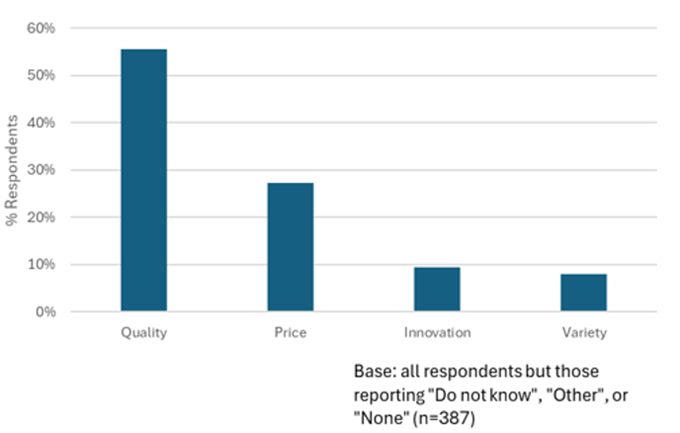

The third main finding that emerges from the survey is the importance of product quality as the key dimension of competition and of export success. Indeed, quality is identified as the most important aspect of both input products and services for export success. Concerning input products, this is shown in Figure 3, which illustrates that for 59% of respondents the most important factor for export success is quality of the input, followed by price (for 30%), product innovation (8%) and product variety (2%). A similar pattern follows beliefs about the relative importance of these product aspects for competing in domestic markets.

Figure 3: Most important aspect of the main input product for success in global export markets

Figure 4: Most important aspect for product success in the domestic market

Since product quality is perceived as the main dimension that is affected by domestic competition, this suggests that improved product quality is an outcome of the competitive process.

Finally, as explained in the previous section, it should be recalled that the incentive to improve quality is perceived by respondents as the main channel through which domestic competition affects export success.

Conclusion

Competition in upstream markets for goods and services is generally believed to have a positive impact on firms’ export success. However, the literature recognizes that due to mechanisms operating in opposite directions, competition in the own product market can either positively or negatively affect exports.

Our survey of European exporting firms active in leading export sectors suggests that domestic competition, both in upstream markets and in an exporting firm’s own product market, is perceived to have a relevant and positive impact on firms’ success in global markets. Moreover, the survey flags that product quality is a key dimension of competition and of export success, even more than price.

These findings suggest that competition in the EU is not an obstacle to reaching a global scale and being competitive in foreign markets. Domestic competition seems instead to boost exporters’ efficiency, quality and innovation, thereby improving their competitiveness.

Authors’ note: The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this article provided by Paolo Buccirossi, Thomas Deisenhofer, Salvatore Nava and Eike Hendrik Radszuhn.

Author Disclosure: The article is a summary of the results of a study funded by the DG Competition of the European Commission, which led to the publication of the study “Exploring Aspects of the State of Competition in the EU”. The report was prepared by a consortium of firms led by Lear and comprising E.CA Economics, Fideres, Prometeia, the University of East Anglia, and Verian. As part of the study, the authors of this article worked for Lear (Elena Argentesi, Livia De Simone, Vincenzo Scrutinio) and for Verian (Stephan Paetz).. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.