In new research, Felix Montag, Alina Sagimuldina, and Christoph Winter study the impact of mandatory price disclosure (MPD) for sellers in the German retail fuel market to determine under what market conditions MPD can reduce prices for consumers.

Since George J. Stigler’s seminal work on the economics of information, economists have known that sellers can derive market power from the fact that consumers need to engage in a costly search to discover how different sellers price similar products. However, digital tools, such as smartphone applications, have reduced the costs of aggregating and diffusing information. Therefore a natural policy tool to curb market power is to force market participants to report their prices and foster the diffusion of this information to consumers. This is the idea behind mandatory price disclosure (MPD) policies.

Although at first sight it may seem that MPD unambiguously benefit consumers, evidence of their effects have been mixed, with prices decreasing after their introduction in some contexts and increasing in others. In a recent Stigler Center Working Paper, Alina Sagimuldina, Christoph Winter, and I set out to understand why MPD policies sometimes lead to lower prices and sometimes to higher ones. Our aim was to identify market conditions under which MPD policies are most likely to benefit consumers. Furthermore, we wanted to understand whether policymakers can affect the success probability of MPD through their design.

To make progress on these questions, we studied the 2013 introduction of MPD in the German retail fuel market. This is the ideal policy laboratory, as the setting combines the availability of very rich data with variation in the market conditions under which MPD was implemented, which allows us to explore the mechanisms.

The policy

After an extensive market investigation that ended in 2011, the German Federal Cartel Office (GFCO) concluded that prices in the retail fuel market were higher than would be the case under functioning competition. In particular, the GFCO found that a lack of price transparency on the consumer side was causing sub-optimal competition. As a result, the GFCO, together with the German Monopolies Commission, called for an increase in price transparency in the downstream market through mandatory price disclosure.

In 2012, the German parliament passed a law forcing all retail fuel stations to report all price changes in real time to a central database managed by the GFCO: the Market Transparency Unit for Petrol. The transparency unit aggregates this data and makes it available to independent operators of smartphone apps or websites in real-time. Access to the data is free and the only condition for the operators to access the data is that they use the data to diffuse it to consumers. In September 2013, the transparency unit went into operation.

Price effects of mandatory price disclosure

A key feature of the German fuel market is the existence of different fuel types, which are all sold at the same fuel stations. The broadest distinction is between diesel and gasoline, between which consumers cannot substitute.

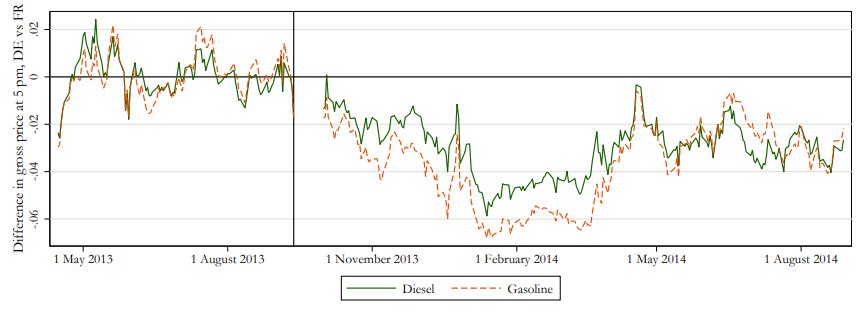

To estimate the price effects of MPD, we used a comprehensive data set of price changes at fuel stations in Germany and France for both fuel types before and after the introduction of MPD. To estimate the price effect of MPD in Germany, we compare the change in prices around the introduction of MPD in Germany to the change in prices in France, which did not experience a policy change. As we show in Figure 1, mandatory price disclosure led to a decrease in prices for diesel and gasoline in Germany of two to four Euro cents for diesel and four to six Euro cents for gasoline. Although this effect might seem small, as it only amounts to around 2% of the gross price for diesel and 3% for gasoline, it is quite large bearing in mind that most of the price of fuel consists of taxes and the price of crude oil and downstream margins account for only around 10 Euro cents.

Figure 1

Why do price effects of MPD differ between fuel types?

Diesel engines are more expensive than gasoline engines, however, the cost per kilometer is lower for diesel, because taxes on diesel are lower. Buying a diesel car is therefore a fixed cost investment to lower marginal costs. It is thus unsurprising that drivers of diesel vehicles on average drive twice as many kilometers as drivers of gasoline vehicles.

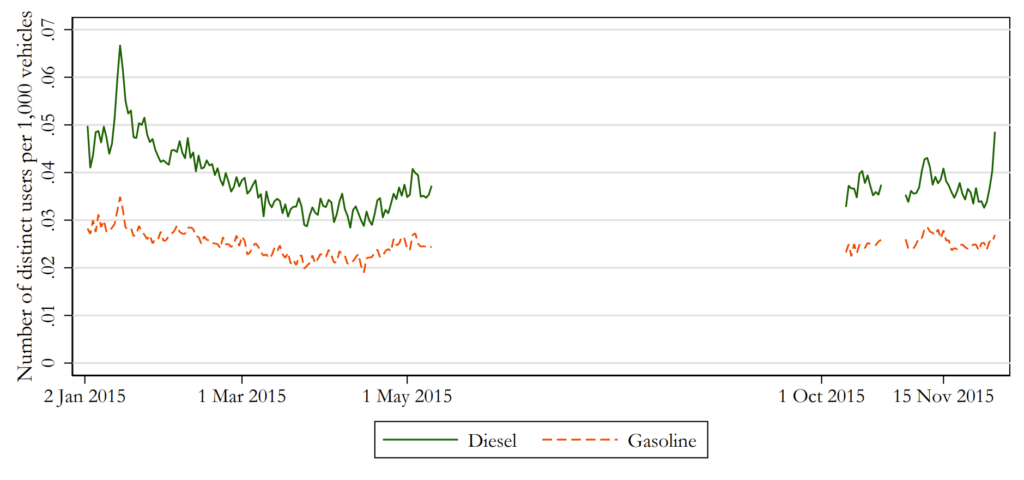

Since diesel drivers drive more and buy more fuel, their expected savings from becoming informed are also higher. We therefore expect that diesel drivers use the information provided by price comparison apps more than gasoline drivers. Using search data from a major price comparison app, we show that the search intensity for diesel drivers is higher than for gasoline drivers. Figure 2 plots the number of unique searchers that search for diesel vs. gasoline prices divided by the number of cars in circulation with a diesel or gasoline engine, respectively.

Figure 2

But if diesel drivers use the price information from MPD more, why are the price effects larger for gasoline? The reason is that price information is not only more valuable for diesel drivers after MPD but also before. They are therefore more likely to pay attention to fuel prices in their local market even in the absence of price comparison apps and are likely better informed ex ante. Thus, the fewer well-informed consumers there are ex ante, the higher is the likelihood that MPD will lower prices. In other words, mandatory price disclosure is more likely to benefit consumers in markets where consumer information about prices is particularly low.

Supply-side factors that shape the effect of MPD

Markets can differ not only according to demand-side factors but also on the supply side. For example, they can differ by how many competitors there are, the identity of the competitors, and the degree of producer information before MPD.

A key advantage of our setting is that MPD was introduced in many different markets that differ in the number and identity of competitors. Unsurprisingly, we find that local monopolists (defined as fuel stations without a rival within 5-kilometer driving distance) reduce prices the least in response to MPD. They are still affected, however, since some consumers (e.g., long-distance commuters) will still consider them as competing with other stations further away. Although the effect is small in magnitude, we find that more competitors strengthen the price-reducing effect of MPD.

Beyond the number of competitors, their identity matters too. We find that stations belonging to brands of vertically integrated oligopolists, which are typically more expensive, reduce their prices by more. In general, we find that price dispersion in local markets declines in response to MPD, because the average price in a local market falls more than the minimum price. This has distributional consequences, since consumers that are well-informed about prices and typically buy around the lowest price in their local market thus benefit less than uninformed consumers who purchase fuel at whatever random price they encounter.

Finally, producer information about prices before MPD matters. The risk is that MPD could improve the visibility of prices for producers and make it easier for them to enforce collusive agreements by punishing sellers that secretly undercut the collusive price, since deviations are easier to detect. This is why MPD in the Danish ready-mix concrete industry increased prices and was repealed shortly thereafter. Since the GFCO documented that producers were already very well informed about prices before MPD, there was limited risk to improve their information through MPD, which limited its downside.

Effective policy design to foster competition

Besides assessing market conditions, is there anything policymakers can do when designing MPD policies to ensure that they will benefit consumers? The key to success is to make sure that the newly available price information is adopted by consumers.

A difference between the implementation of MPD for German retail fuel stations as opposed to similar measures in Australia or Chile was that the barriers for app developers to access the price information was particularly lower. Only a year after its start, the GFCO listed 44 websites and app developers that diffused the price information to consumers.

Another finding of our paper is that when local radio stations broadcast the price information over the air to raise awareness of the existence of this price information, this further reduces local fuel prices. We conclude from this that policymakers can use complementary information campaigns to further enhance the pro-competitive effect of MPD.

Conclusion

We set out to understand under what conditions MPD is likely to benefit consumers. The introduction of MPD in the German retail fuel market provides valuable lessons for policymakers considering MPD and allows us to identify several key success factors. First, it is important to determine whether the market conditions are conducive to a pro-competitive effect of MPD. This is particularly true when consumers lack information about prices before the policy, producers are already well informed, and there are three or more competitors. Second, we find that it is crucial to design the policy in a way that lowers barriers for information diffusion and makes sure that consumers are reminded of the availability of this data. With this in mind, mandatory price disclosure can be a successful addition to the policy toolbox used to make markets more competitive.

Author Disclosure: the author reports no conflicts of interest. You can read our disclosure policy here.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.