In new research, Tommaso Crescioli & Toon Van Overbeke find that small business owners and their families who have lost revenue share to rising market concentration among big businesses have turned to far-right political parties to express their grievances.

How does market power affect wealthy democracies? For capitalist democracies to be sustainable, they need to inspire confidence among citizens that markets can offer fair opportunities and rewarding economic prospects. Markets, however, do not always work that way. In the United States in the late-19th century, Louis D. Brandeis helped intellectually spearhead a populist campaign against monopolies, above all Standard Oil, who had come to dominate the economy during the “Gilded Age.” This anti-monopoly sentiment produced in 1890 the U.S.’ first antitrust law, the Sherman Act, which helped rebalance the economy in favor of small businesses.

In 1950s France, the populist Poujadist movement similarly harnessed the economic grievances of small shopkeepers lashing out against the government’s pursuit of economic globalization and industrialization. The Poujadists claimed that small businesses and artisanship were the only way for ordinary people to get ahead, and that these pathways were now being crushed by Paris and the nation’s corporate and industrial elite.

The grievances of small business owners in the face of rising market power among big business remains a concern in most democratic societies. Recent evidence suggests competition is declining in the U.S. and other regions of the world. According to this literature, a mix of globalization, digital innovation, and muted antitrust enforcement has enabled large firms to monopolize markets and outmuscle smaller competitors. Recently, these concerns about deteriorating competition have been championed by Neo-Brandesians who, like their namesake, consider large corporations an economic and political threat. In Europe, similar concerns about the ability of local enterprises to compete in 21st-century capitalist markets have fueled the neo-Poujadist elements of the French yellow-vest movement.

Despite the increased public attention on how high market concentration harms small business and democracy, academics have paid little attention to how small businesses respond politically to market concentration. Our research pursues this question by studying the political behavior of small business owners and their families in Europe in response to growing market power. Small business owners, such as the local butcher, continue to play a critical role in modern societies. Small businesses comprise around 93% of non-financial companies in Europe and employ some 30% of the workforce. As such, these firms play an essential role in stimulating local and national economies and fostering local communities. Small business owners also make up a core part of the middle class in Europe, and thus often underpin centrist, moderate parties. If the market power of big business is growing at the expense of small businesses, we thus expect this to be reflected in dissatisfaction among the latter’s stakeholders: owners, families, employees, and the local communities dependent upon them. This would likely mean shifts away from incumbent centrist parties and towards parties at the extremes of the ideological spectrum.

Rising market concentration harms small business

Our analysis starts with a review of how much small businesses (defined as firms with fewer than ten employees) contributed to regional industries (defined using NACE 2-digit codes) from 2002-2018 and the number of mergers and acquisitions that have occurred every year over this same time period. Figure 1a shows that small businesses’ average revenue share in a regional industry has dropped by almost 6% since 2002. The European debt crisis, which occurred from 2009-2010, accelerated this trend. Yet, two things are important to emphasize. First, the negative trend started before the debt crisis. Secondly, small businesses never recovered their market share and continue to trend downward.

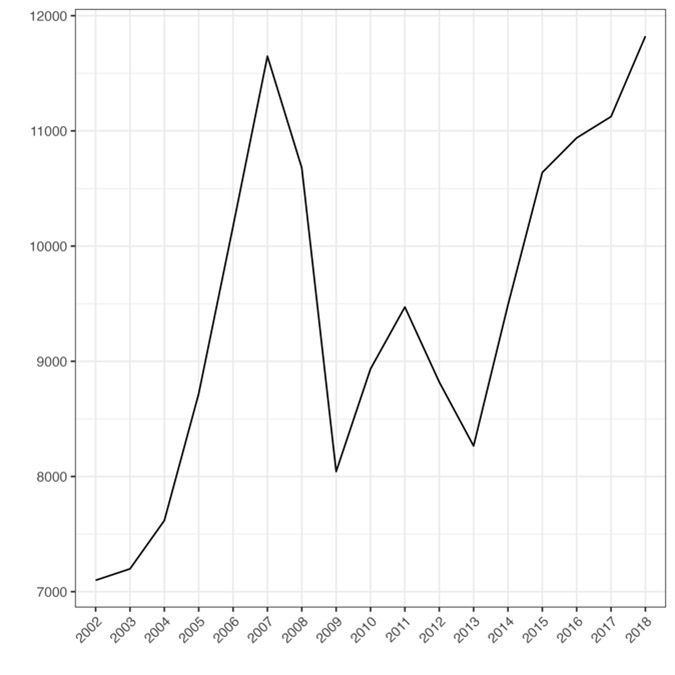

When we turn our attention to panel 1b, we can see that the number of mergers has been on the rise from 2002 to 2018. The 2008 financial crisis slowed down this trend. However, merger activity began to climb again beginning in 2013 and recovered its peak level of activity by 2018.

Figure 1. Small businesses’ share of revenues in the regional industry (1a) and the number of mergers per year (1b)

a) Small businesses’ region-industry revenues share b) Mergers per year

The next step of our research was to establish a stronger relationship between merger activity and the economic performance of small businesses for 14 Western European countries. We found that the firm-level regional revenue share of small businesses dropped by 10-13% after increases in market concentration corresponding to 1145 points of the HHI index on average due to M&A. Furthermore, the probability of these small businesses exiting the market after increases in merger activity rose by 7-9%.

Aggrieved small business owners and families turn to the far-right

Once we established the negative relationship between merger activity and small business activity, we explored how the latter’s losses translated at the ballot box. Using individual-level data on small business owners and their family members, we first document that mergers leading to higher market concentrations result in owners and their families being 19-25% more likely to reject incumbent parties and 9-13% more likely to vote for non-incumbent far-right parties. We do not find that this market concentration effect significantly encourages owners or the families to vote for leftist parties.

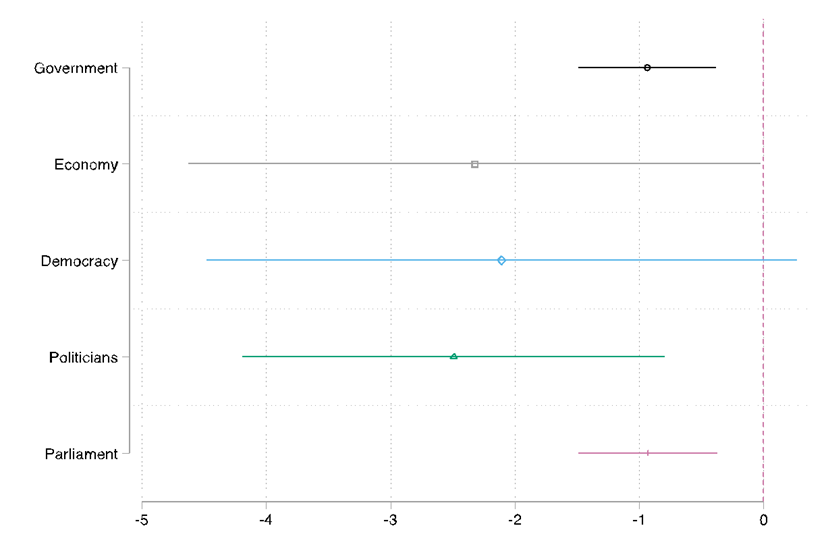

How can we explain this tendency to vote for far-right parties? First, extensive research on various economic shocks shows that the far right is particularly successful at attracting voters who experience or fear the loss of socio-economic status. In most societies, small business owners and their families rely on their firms not only as a source of income but also as a source of social status. Second, we know from previous work that citizens with low or declining levels of trust in key democratic institutions are more likely to reward political parties, such as far-right parties that challenge established political norms. Whether due to the perception of government economic failures or outright capture by corporate interests, it is therefore likely that small business owners and their families express grievances by supporting political parties that challenge existing institutions. By contesting this status quo, the agendas of radical right parties promise solutions to small business owners, including protection against culprits such as competition from globalization. In Figure 2, we provide evidence of this increasing institutional distrust. We observe that high concentration from increasing mergers decreases the trust of small business owners and family members in the economy, the government, democracy, politicians, and parliament.

Figure 2. Effect of high-concentration increasing mergers on individual-level attitudes

Note 2: For example, the estimate for “Parliament” shows that for owners and family member of small businesses in industries experiencing a merger, their trust in parliament has decreased by approximately one point more than owners and family members not experiencing a merger.

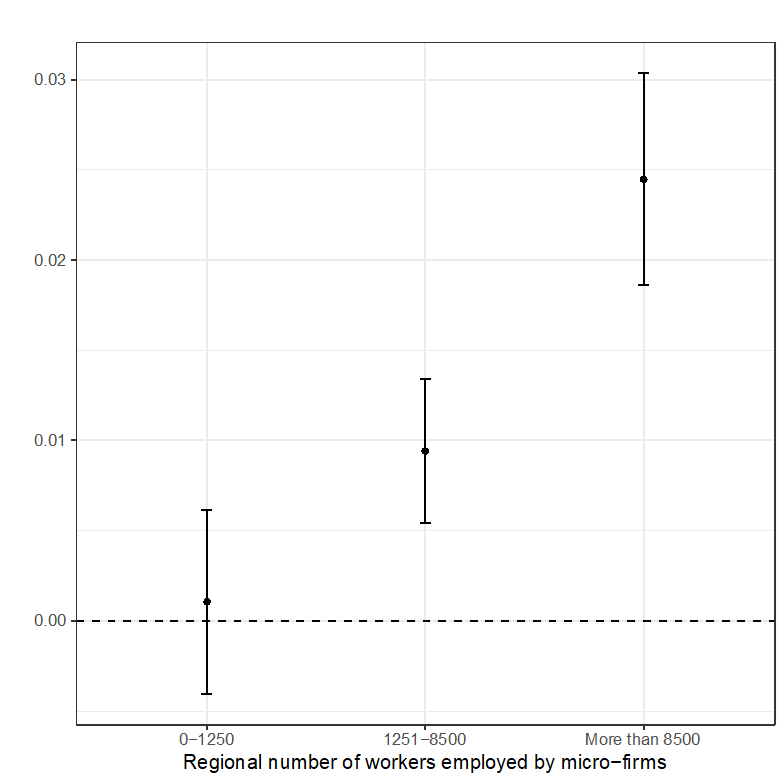

We also investigated how these individual-level mechanisms reverberate in national elections using constituency-level electoral results. Our analysis reveals that a 5.1% decline in the share of regional revenues going to small businesses increased the vote share of non-incumbent far-right parties by up to 12 percentage points. This effect grows with the average number of people employed by small businesses in a region.

Figure 3. Effect of the declining regional economic weight of small business on non-incumbent radical right parties vote shares by people employed by small business in the region

Conclusion

To conclude, we show that increasing market concentration has been a critical driver behind political fragmentation and the shift toward far-right populist parties in recent years. Our findings echo the arguments made by Francis Fukuyama in Liberalism and its Discontents, wherein he began to interrogate the democratic implications of economic consolidation driven by the pursuit of efficiency, which has resulted in the widespread closure of small businesses and the rise of large corporations.

The tensions of capitalism have generally been expressed as a struggle between capital and labor. Today, it is also between small and large businesses. In both the U.S. and Europe, governments are implementing industrial policy to build up national champions that can compete on the international market. Our research exposes another tension in this strategy for wealthy democracies.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.