Piergiuseppe Fortunato, Tanmay Singh, and Marco Pecoraro research the behavior of populist leaders and parties around the world and how their policies influence subsequent government spending. Their research shows that populists from either side of the ideological spectrum have very little in common in terms of policy despite similar anti-elite rhetoric.

The year that many identify with our current populist zeitgeist, at least in the West, is 2016, when Donald Trump was elected as president of the United States and the United Kingdom abandoned the European Union after an astounding referendum. But the emergence of populist movements in continental Europe, and the elections of leaders such as Hugo Chavez, Vladimir Putin, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan in leading emerging economies, predate that catalytic year and date back to the turn of the twenty-first century.

We tend to identify populists, especially when in power, with certain specific policy traits, ranging from loose fiscal policy (particularly sensitive to popular demands) to the disregard of liberal rules concerning the rule of law or social rights. But populism can be better described as an approach to politics rather than a singular and comprehensive way of ruling. It is a tactic (a political communication tactic to be precise) that has long been used around the world, at least since the nineteenth century, to gain and maintain power.

As a matter of fact, the most widely accepted definition of populism regards it simply as a set of ideas focused on a fundamental opposition between the “pure” people and the “corrupt” elite. Populism is therefore only a thin ideology, meaning that it addresses only part of the political agenda. Consequently, almost all relevant actors across the political spectrum can combine populism with a host ideology, normally some form of nationalism on the right or some form of socialism (including democratic socialism, which doesn’t entail the state ownership of means of production) on the left.

Globalization and populisms

The latest wave of populism has been associated with backlash against the globalization of the world economy. In the mid-1990s, right before the blossoming of populist movements in all corners of the world, the trade round that created the World Trade Organization (WTO) was successfully concluded at Marrakesh, paving the way for the freer international movement of firms, capital and people.

Making investment freer tilted the playing field in favor of capital, the more mobile of the factors of production, and increased its bargaining power compared with that of labor by tapping into cheaper labor markets. Real wages have since stopped growing in most countries, or have done so to a much lesser extent than the return on capital. The consequence is that in both developed and developing economies, inequality has reached unprecedented heights. At the same time, increasing immigration, especially within the context of economic insecurity, has fostered cultural anxiety, a lack of social trust, and a sense of ethnic competition.

In this context, left-wing (socialist) populists have targeted inequality and neoliberal capitalist institutions like the WTO with redistributive policy proposals. On the other side, right-wing (nationalist) populists have focused on shielding voters from immigration. A vast literature upholds this narrative, and indeed economic insecurity has been shown to play a significant role in explaining voters’ behavior.

The different notions of “the people” and the different enemies that left- and right-wing populists identify illustrate this dichotomy. Right populism conflates “the people” with an embattled nation confronting external threats to its security and welfare: immigrants, refugees, Islamic terrorism, international conspiracies, and so on. The left, in marked contrast, defines “the people” in relation to the social structures and institutions—for example, state and capital—that thwart their aspirations for self-determination. It is a construction that does not necessarily preclude hospitality towards people from other ethnicities or nationalities.

From rhetoric to reality

In a recent working paper, we document the multifaceted nature of the populist phenomenon and show how left-wing populist governments, which have built their success on protests against inequality and capitalist institutions, are generally associated with increases in public and social spending. Conversely, right-wing populist governments, which are more likely to adopt rhetoric based on anti-immigration and security stances, are characterized by a more orthodox management of the public budget.

We employ a cross-country dataset that codes populist leaders based on the workhorse definition of populist in political science, i.e. political leaders who prioritize the struggle of the people against the elites in their political campaigns and communication. It also distinguishes between left- and right-wing populists depending on whom the populist targets: economic elites and capitalist institutions or foreigners and minorities.

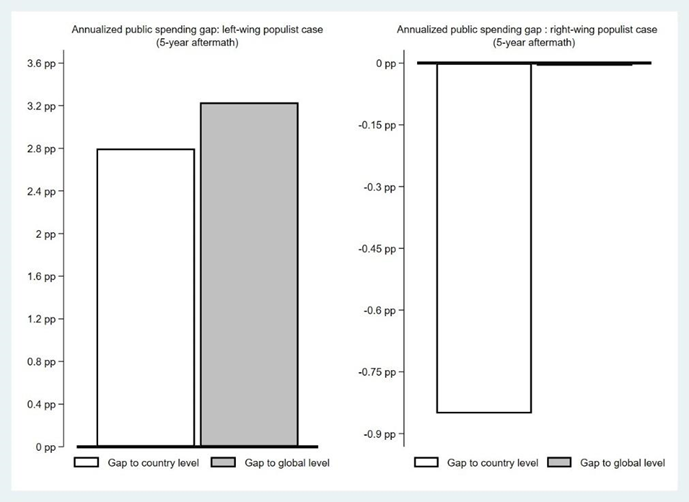

Figure 1 gives a hint of what are the immediate consequences on public spending of left- and right-populist parties taking power. Countries tend to overspend around three percentage points of GDP per year when a left-wing populist takes control of the government budget, both compared to that country’s typical long-run spending rate (white bars) and the contemporary global average spending rate (gray bar). Conversely, countries where right-wing populists came to power experience a reduction of almost one percentage point of GDP in government spending compared to their country’s typical long-run spending rate (the reduction with respect to the global average is only marginal).

Figure 1

The results of Figure 1 are not conditioned on economic events surrounding the populist entering office nor on year-over-year dynamics, and they do not use a strict control group. All this is especially important since countries that experience a populist takeover, or a left-wing populist takeover versus a right-wing one, is likely not random with regards to the country’s incumbent economic situation, including the government’s economic policy and public budget.

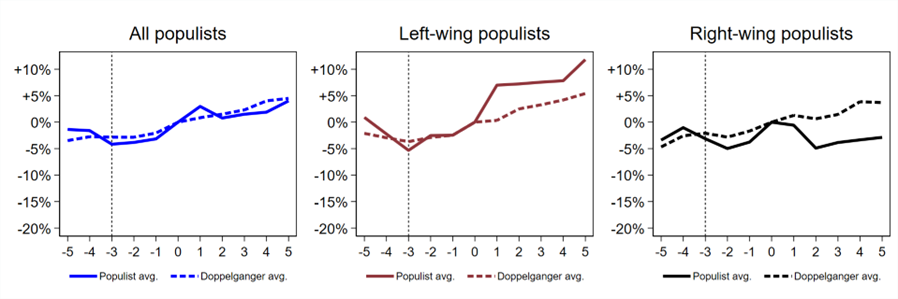

We get more rigorous in Figure 2, where we apply the so-called synthetic control method (SCM). The SCM helps take into account the economic events surrounding the populist entering office by creating a “synthetic” comparison group (or counterfactual) that closely matches the economic characteristics of the group of countries under exam.

The figure shows how the spending profile of left-wing populist governments diverges visibly from the trend we would have expected in the absence of their ascent, amounting to about a five-percentage-point relative increase in spending after five years. The spending pattern of right-wing populists likewise diverges markedly from the counterfactual, but in the opposite direction. After five years, spending is around five percentage points below the counterfactual. Not surprisingly, when aggregating the two groups, positive and negative differences tend to balance out.

Figure 2

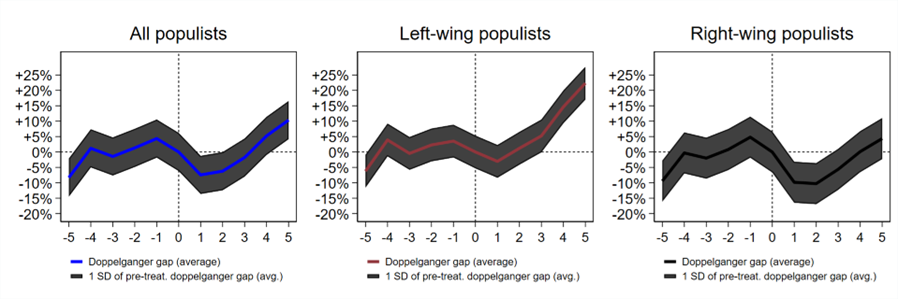

When we look at the composition of government expenditures, we find that the change of trend can be at least partly explained by a rise (fall) of social expenditure in left- (right) wing populist governments. Figure 3 below shows the pattern of education spending. Government expenditure on social welfare is also affected.

Figure 3

Nowhere has the dichotomous nature of populist governance emerged more clearly than in Italy. The country was governed by a populist coalition headed by a left-wing populist movement (the Five Star Movement or M5S) between 2018 and 2019, while a right-wing coalition headed by a right-wing nationalist populist party (Brothers of Italy) achieved power in September 2022. Interestingly, the flagship policy of the M5S government was the introduction of a new minimum income scheme (the “Citizenship Income” or “reddito di cittadinanza”) that cost the state around nine billion euro a year. The Brothers of Italy almost entirely removed this social welfare provision during the first months of its government.

Conclusion

A vast literature has examined the reasons behind the recent emergence of populist rhetoric and the success of populist leaders in democratic countries all around the world. Many authors coincide on the relevance of globalization in setting in motion a series of economic shocks and a shift in the income distribution that might have aggravated existing social and cultural divides and fueled anti-establishment political movements.

Much less effort, at least until recently, has been devoted to examining the behavior of populist leaders, and their policy choices, once in power. This asymmetry can be partly explained by the fact that the definition of populism on which both political scientists and economists now converge is extremely “loose” or imprecise. As such, this definition ends up embracing a wide variety of political movements with visions of society, objectives, and priorities that can be extremely different. The glue is simply the narrative and the tone of the political propaganda. But a tactic to generate consensus can be consistent (and in fact it is) with several strategies to govern a country.

Authors’ Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article and the underlying research are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or the Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.