Kevin Murphy reflects on his seminal work with the late Michael Jensen, reassessing their influential findings on CEO compensation in light of the dramatic changes in executive pay practices and market conditions since the 1990s. In this piece, Murphy shares the journey of their research collaboration, the challenges they faced, and the evolution of their thoughts on executive compensation.

Mike’s Early Work on CEO Pay

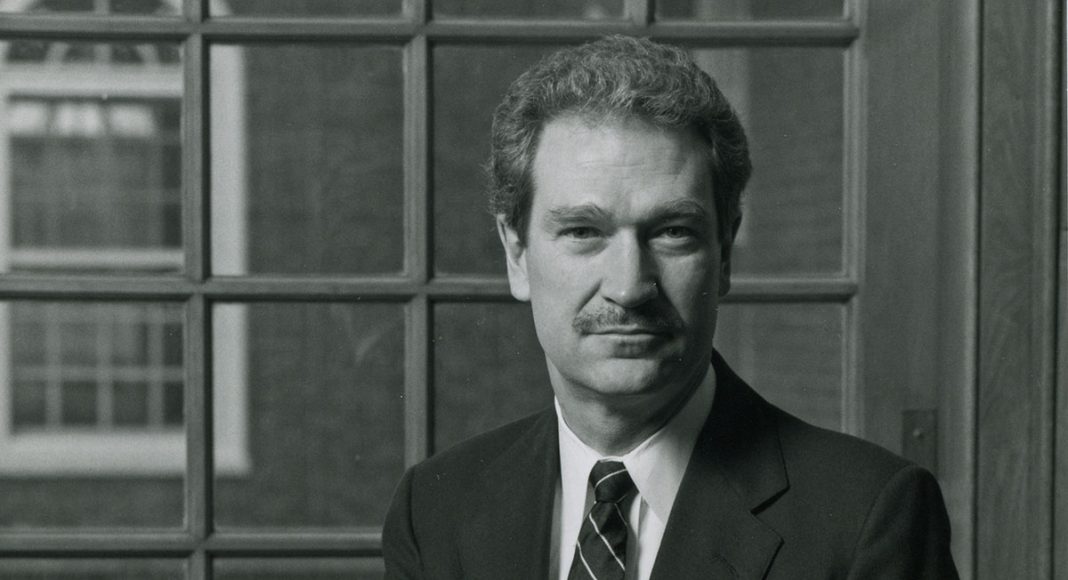

When I joined the University of Rochester’s Graduate School of Management (now the Simon School) as a newly minted assistant professor in January 1984, my thesis advisors from the Chicago Economics Department warned me to be wary of Michael Jensen, the most prominent and influential faculty member at the school. Their well-intended warnings proved unnecessary: in short order Mike became my mentor, co-author, colleague, and life-long (if not always uncomplicated) friend.

By the early 1980s, Mike and Bill Meckling’s 1976 paper “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure” was already established as the leading paradigm for empirical corporate finance. Largely missing from the Jensen-Meckling treatise, however, was the role that executive incentive contracts play, or could play, in mitigating the agency problems between managers and shareholders. Mike became highly intrigued by executive compensation and, along with colleague Jerry Zimmerman (co-founding editor of the Journal of Accounting and Economics), organized the “Conference on Management Compensation and the Managerial Labor Market” in April 1984, published as a special issue of the JAE in 1985. The conference—and the Jensen-Meckling paradigm—helped launch executive compensation as a legitimate topic of academic research in accounting, finance, and economics.

My personal contribution to the April 1984 conference was using time-series data with executive fixed effects to uncover a statistically positive pay-performance elasticity (e.g., the percentage change in compensation associated with a percentage change in the value of the firm). While acknowledging the statistical significance, Mike kept pushing on the economic significance: was the estimated elasticity really large enough to provide meaningful incentives? We developed a construct we called the pay-performance sensitivity that measured the “effective ownership share” akin to the manager’s ownership share in Jensen-Meckling, but including all sources of incentives (e.g., stock and option holdings, bonuses, year-to-year salary adjustments, and the probability of performance-related terminations). In our 1990 Journal of Political Economy article (Jensen-Murphy 1990a), we concluded that the wealth of a typical CEO changes by only $3.25 for every $1,000 change in shareholder wealth, hardly enough to get CEOs to take projects that increase shareholder wealth and avoid projects that decrease shareholder wealth.

Mike and I considered myriad explanations for what we believed were unexpectedly low observed pay-performance sensitivities, including risk aversion, limits to credible contracting, imperfect performance measurement, and CEO production functions. We concluded that the most plausible explanation reflected the role of third parties in the contracting process, including Congress, labor unions, and media pundits who influence pay (by, say, truncating the upper tail of the earnings distribution for CEOs) but have no real ownership stake in the company. Indeed, the role of “uninvited guests to the bargaining table” has been a primary theme of our work on executive compensation since a New York Times op-ed article (Jensen-Murphy, 1984, co-authored a few months after I joined Rochester) and continuing through Mike’s last published journal article (Murphy- Jensen, 2018).

The low pay-performance sensitivity was not our only compensation-related observation where it was difficult to reconcile theory and evidence. Baker-Jensen-Murphy (1998) analyzed several such practices, including: the absence of meaningful incentive systems throughout the organization (not just in the executive suite); problems with promotion-based incentive systems (including tenure and up-or-out promotion systems); the absence of relative-performance measures; profit-sharing plans for low-level workers; subjective performance measurement; and biased or inaccurate performance evaluations. While we tackled some of these puzzles in our future research, we left the rest to others (and, with nearly 3,400 Google cites and climbing, there have been quite a few others).

Throughout most of his career, Mike prided himself on taking a “positive” rather than a “normative” approach to research (i.e., explaining the world rather than trying to fix it). Mike and Bill, for example, considered the emerging (and highly mathematical) optimal contracting literature as normative: structuring the principal-agent relationship to provide incentives to maximize the value of the firm. In contrast, Mike and Bill viewed their own work as positive: understanding and explaining existing practices as the equilibrium of a nexus of contracts primarily between managers, shareholders, and debtholders, but also (in Mike’s later work) including employees, customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders (including those “uninvited guests to the bargaining table” discussed earlier).

From time-to-time, though, Mike would happily cross into the normative world, such as our Harvard Business Review article “CEO Incentives: It’s Not How Much You Pay, But How” (Jensen-Murphy, 1990b) that many have claimed contributed to the explosion in executive stock-option grants in the 1990’s. Our own view is more nuanced, since we maintain that the option explosion largely reflected the unintended consequences of Congressional acts designed to reduce levels of CEO pay (Murphy-Jensen, 2018).

Mike’s Reassessment of CEO Pay

In late 2003, Mike and I were commissioned by the Compensation Committee of a major international corporation to write a high-level “think piece” on executive compensation, addressing such issues as the appropriate objective function, history and trends in CEO pay, and strengths and weaknesses of current practices. More broadly, the Committee asked us to consider whether there was scope for a new intellectual framework for compensation in the current economic, political, and governance climate. We asked our friend and colleague Eric Wruck to assist us in this project. We presented our report to the Committee in January 2004 and subsequently (with their permission) submitted the report as an ECGI working paper (Jensen-Murphy-Wruck, 2004).

The project made us focus on how much had changed in aspects related to CEO pay from 1990 to the early 2000s. First, the use of stock options exploded in the 1990s, tripling the inflation-adjusted level of CEO pay in the S&P 500 in less than a decade. While Mike and I had indeed advocated for an increased reliance on stock options and other forms of equity-based pay, our naïve expectation was that such increases would be accomplished through reductions in other forms of pay (such as salaries and accounting-based bonuses). What actually happened was that companies added increasingly generous grants of stock options on top of already competitive pay packages, without any reduction in other forms of pay and showing little concern about the resulting inflation in pay levels (Murphy, 2013, Section 3.7).

Second, we had long known that firms, on average, experienced consistent excess returns following public earnings announcements. Skinner and Sloan (2002) documented that the relation between excess returns and quarterly earnings announcements follows an S-shape depending on announced earnings relative to analysts’ consensus forecast errors. In particular, stock prices react strongly and positively to small positive earnings surprises, but there is not much additional stock-price reaction to larger surprises. Similarly, stock prices react strongly and negatively to small negative earnings surprises, but there is not much additional stock-price declines following larger surprises. The implication is that executives holding stock or options have strong incentives to beat analyst expectations by a little, but not by a lot. And, executives have strong incentives to avoid missing analyst expectations, but if they are going to miss them they might as well miss them by a lot (since the stock-price penalty for missing by a lot is not much worse than missing by just a little). While the incentive implications are similar to those of typical accounting-based bonus plans (where no bonuses are paid before some performance threshold is met, and then bonuses are capped at a higher performance threshold), the “fix” is more challenging: bonus plans can be tweaked to reduce incentives to manage earnings, but the similar incentives from the reaction to earnings announcements is coming from the market and not from anything under the direct control of the Compensation Committee.

Third, by the early 2000s it became apparent that the shares of many firms (especially new-economy firms) were grossly overvalued, and in many cases propped up by questionable or fraudulent accounting, legal, brokerage, investment banking and other financial practices. Share prices plummeted, and many large U.S. companies—including Enron, WorldCom, Qwest, Global Crossing, HealthSouth, Cendant, Rite-Aid, Lucent, Xerox, Tyco International, Adelphia, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Arthur Andersen—became embroiled in accounting scandals. Without asserting causality, a common feature of most of the scandal-ridden firms was an extraordinary reliance on stock options in executive compensation packages. Overvaluation is a challenge for Compensation Committees: it is difficult to provide incentives for executives to hasten price corrections in their own company’s stock, especially when much of their existing wealth is held in equity or stock options.

These observations (and others) led Mike and me to reassess many of our underlying assumptions regarding CEO pay. (My personal reassessment also included spending a year on leave at a major compensation consulting firm, learning first-hand how the sausage is produced). For example, we implicitly assumed that executives and directors fully understood the opportunity cost of stock options and would only grant options if the potential benefits (including effort and retention) outweighed the cost. We came to recognize that risk-averse and undiversified executives will rationally value unvested stock options well below their opportunity cost, and that directors would too often presume that the cost of granting options was near zero since they could be granted without an accounting charge and without a cash outlay. As a result, too many options were granted to too many people (Hall-Murphy, 2002, 2003; Jensen-Murphy-Wruck, 2004, pp. 38-43).

Similarly, our 1990 conclusions advocating the increased use of equity-based pay was implicitly based on the efficient market hypothesis. In the extreme, when markets are strong-form efficient, shareholder return (or perhaps shareholder return relative to peers) is a compelling performance measure for CEOs, since stock returns capture the long-run present value of actions and decisions CEOs take and make today. For most applications, the distinction between semi-strong efficiency (where the stock price incorporates all publicly available information) and strong-form efficiency (where the stock price incorporates all knowable information, including information held by insiders) is not particularly important, since even inside information comes out eventually (and is likely, in any case, to be incorporated into stock prices long before showing up in accounting earnings). The distinction between semi-strong and strong-form efficiency is much more important in the context of executive pay, since the information making the market not strong-form is precisely the information held by insiders who are compensated based on the stock price. Executives, for example, have better information than shareholders (or directors) on whether the company beat earnings expectations through remarkable performance, or through earnings management (Jensen-Murphy-Wruck, 2004, pp. 87-97). Similarly, executives likely receive signals (such as internal supply-chain data) indicating whether their firms are overvalued relative to expected future cash flows (Jensen, 2005; Jensen-Murphy-Wruck, 2004, pp. 44-49).

We used the commissioned report (Jensen-Murphy-Wruck, 2004) as the basis for an invited (and accepted) book proposal from the Harvard Business School Press, ultimately titled CEO Pay and what to do about it: Restoring Integrity to both Executive Compensation and Capital-Market Relations. The manuscript was “mostly written” by 2011, with 10 (out of 14) completed (or “mostly competed”) chapters and 300 pages of text. While many of the chapters have been published as standalone papers (e.g., Jensen (2005), Fuller-Jensen (2002), Murphy (2013), and Murphy-Jensen (2018)), the biggest regret in my professional career is not bringing this book to publication. I have three (but collectively non-compelling) excuses.

The first was the untimely death from cancer of our third co-author, Eric Wruck, in 2011. Eric was a wonderful, intelligent, and good-natured soul with a heart of gold. His passing took the wind out of our sails.

The second was Mike’s contemporaneous research agenda with Werner Erhard, starting with a focus on leadership (including short courses taught at several Universities) and evolving into a positive theory of integrity. The “excuse” is not about the allocation of Mike’s time: Mike was the ultimate multi-tasker and was passionate about both projects. The larger issue was Mike’s intuition and insistence that “integrity” (as he and Erhard usefully distinguished from morality and ethics) should be featured prominently in every chapter we had written on executive compensation (including several we thought were completed). The problem was not with Mike’s definition of integrity as a factor of production—value would clearly be increased if managers had incentives to announce that their over-valued company’s stock price was too high, or that they couldn’t meet analysts forecasts without cheating—but we struggled to find a solution that could be implemented through the compensation system.

Third, the journey was always more fun than reaching the finishing line. Mike and I would schedule multiple talks each week and would spend a week together (either at my home in California or his homes in Vermont and Florida) every couple of months. Our discussions were consistently rigorous and intellectually challenging, and working with and learning from Mike has been the highlight of my professional career.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.