Giovanna Massarotto writes that antitrust actions against major technology companies like AT&T, IBM, and Microsoft over the past century, though imperfect, have positively impacted innovation and competition in the computer industry by restricting anticompetitive behavior while allowing breakthrough technologies to flourish through carefully crafted remedies. This stands in contrast with Europe, which has seen less homegrown innovation from its technology companies.

Massarotto will discuss further the impact of antitrust on innovation next week at the Stigler Center’s 2024 Antitrust and Competition Conference—Antitrust, Regulation and the Diffusion of Innovation. The conference will be all day April 18 and 19, and all panels will be livestreamed. You can register here to join online.

“Innovation is like a manna from heaven,” over which policymakers have little control, according to Robert Solow’s model. Despite this, if we look at the computer industry, antitrust seems to have achieved some important results. In this article, I will briefly review how antitrust enforcement against AT&T, IBM, Microsoft and Intel spurred innovation in the computer hardware and software industries.

AT&T, probably the most famous case in United States antitrust history, is well-known for the decision in 1982 that required the telecommunication monopoly to break up into several companies. However, the AT&T antitrust story is much more complex and fascinating with clear fundamental effects on the computer economy we live in today. Historically, AT&T owned Bell Labs—also called the “idea factory”— which was the birthplace of several Nobel Prize-winning inventions. Probably the most famous invention at Bell Labs was the 1947 invention of the transistor, for which Bell Labs scientists William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1956. The transistor represents the beginning of the digital age and is present in all our modern digital devices.

This part of history is well known. Less remembered is how the transistor was widely adopted so rapidly. Here antitrust comes into play. This breakthrough technology was sold under the AT&T license. In the mid-twentieth century, AT&T was in the crosshairs of the Department of Justice Antitrust Division for possible monopolistic practices. The antitrust investigation, opened in 1949, was settled by a consent decree in 1956. AT&T agreed to implement several remedies to address the antitrust concerns raised by the DOJ, including “to grant to all applicants non-exclusive licenses for all existing and future Bell System patents,” which included the transistor. The decree also required AT&T to provide, upon payment of reasonable fees, the technical information needed for manufacturing the equipment covered by the patent license.

A variety of present-day economists have conducted studies to assess the impact of this remedy on economic growth and innovation. Professors Peter Grindley and David Teece considered AT&T’s licensing policy as “one of the most unheralded contributions to economic development—possibly far exceeding the Marshall Plan in terms of wealth generation capability it established abroad and in the United States.”

Intel’s co-founder Gordon Moore considered the AT&T consent decree of 1956 “one of the most important developments for the commercial semiconductor industry.” It is important to remember that AT&T agreed to the compulsory license remedy to end the DOJ antitrust investigation started in 1949. Remedies enshrined in consent decrees are typically offered by the investigated parties. Thus, they are the result of a ‘consensus mechanism’, benefiting from input of the same company under investigation, which often has created the market that is accused of having been monopolized.

The Story of Unix

The 1956 consent decree against AT&T also had the incidental consequence of paving the way to the open-source movement in the computer industry and being instrumental to the development of the first internet network—Arpanet.

Although Unix is considered the most successful operating system “of all time,” few remember how antitrust played a vital role not only in Unix’s success but also in the creation of the free software “open source” movement. Thus, let us go back to the 1956 AT&T consent decree. This consent decision not only required AT&T to license its patents, but it also precluded the telecommunication monopoly “from engaging in any business other than the provision of common carrier communications services.” This meant that AT&T could not enter into the computer industry. AT&T’s counsel concluded that in the 1970s when Unix was invented, AT&T was restricted from commercial exploitation as a result of its agreement from 1956.

Therefore, the company decided to license Unix to several universities under academic licenses for research and academic purposes to avoid antitrust repercussions. AT&T made it clear about having no intention of entering the software business. AT&T denied assistance or bug fixes which “forced users to share [solutions] with one another.” In other words, the 1956 terms of the consent decree and AT&T’s decision to provide ‘no support’ to Unix users led computer scientists who were using Unix to solve technical problems and increase Unix’s performance through a joint effort.

But that’s not all. In 1979, the University of California, Berkeley developed “a new delivery of Unix software” the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD), which was used in the creation of the first internet network—Arpanet. BSD is probably the most important example of a Unix like operating system before Linux developed in the 90s. Unix-like operating system means they behave similarly to a Unix by sharing a common structure and characteristics. In 1974 Vint Cert and Robert Kahn, “the fathers of the Internet” implemented the internet protocols, TCP/IP protocols, and Berkeley “integrate[d] the protocols into the Unix software distribution,” enabling the connection of “about 90% of the research university community.” Different Unix variants included open source variations licensed through BSD licenses, which include a set of permissive free software licenses.

The AT&T antitrust story continued to shape the computer industry. In 1974, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a new antitrust lawsuit against the telecommunication giant. From 1981 through 1983, the head of the DOJ Antitrust Division was William F. Baxter, a renowned Stanford Professor, who developed the so-called ‘Bell Doctrine.’ Because regulated monopolies have incentives to monopolize markets where their service represents an input, it was recommended to ‘quarantine’ the monopoly service from the other related markets. About 30 years after the 1956 antitrust consent decree, the government finally won its battle to break up its telecommunications monopoly. AT&T agreed to divest its local operating companies, the so-called Baby Bells. Because the 1982 antitrust consent decree was a modification of the 1956 version, it was referred to as the Modification of Final Judgment (MFJ). AT&T was reorganized into seven independent Regional Bell Companies (RBOCs) by remaining the owner of the long-distance line. AT&T continued to own Bell Labs after the divestiture, but much of its revenue was cut off given that about 80% of the funds for research stemmed from Bell operating companies.

However, AT&T was released from its earlier obligation that had prevented the company from entering into the computer industry. AT&T could now sell Unix by setting a “totally new set licensing terms.” As a reaction, in 1983 the American free software movement activist and programmer, Richard Stallman, announced “Free Unix!” through the GNU project. In 1989, Stallman wrote the well-known free software license— GNU General Public License (GNU GPL). A couple of years later, the GNU GPL license was used to distribute a Unix-like operating system—Linux, one of the most widely used open source operating systems today.

Not only do Google Android, Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Facebook (now Meta) run on Linux, but so do most supercomputers.

The IBM Unbundle and the Software Industry

Interestingly, many attributed the development of the software industry to another antitrust-related intervention in the computer industry—the IBM antitrust case back in the 1960s. Between 1967 and 1968, IBM’s competitors, following the lead of the once major supercomputer company Control Data Corporation (CDC), urged the DOJ Antitrust Division to file an antitrust complaint against IBM for monopolization conduct in the computer industry. Although the DOJ was seriously considering taking formal action against IBM, in December 1968 the CDC decided to start its own suit accusing IBM of engaging in a series of monopolistic practices that were harming CDC’s business and growth.

IBM’s executives started conversation with senior DOJ attorneys and opted for announcing the unbundling of its services before the DOJ filed any antitrust suits. The executives decided that the risk of an antitrust lawsuit and potential damages, was high enough to threaten IBM’s business existence. IBM understood from their past the consequences of an antitrust lawsuit. Beyond being a constant target of antitrust investigations, in 1913 IBM’s famous Chairman Thomas Watson Sr. “was sentenced to a year in jail” for criminal antitrust violation while he was executive at National Cash Register Company. The Court of Appeal found the case defective requiring the government to retry it, which never occurred. But the case had strong media coverage. President Wilson was even asked to pardon Watson and the other executives involved. His son, Thomas Watson Jr., became the chairman of IBM in 1956 serving until 1971.

The IBM unbundling took place in the summer of 1969 and implied the unbundling of services previously part of IBM’s hardware offerings, including software offerings. Although this did not stop the DOJ from filing the antitrust complaint that same year, the antitrust proceeding famously ended with the U.S. dropping the case. After 15 years of investigation and an estimated $16.8 million spent by the government, Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust William F. Baxter argued that the case was “without merit.”

Maybe it was not entirely due to the success of the IBM unbundling decision, but many in the computer industry said that the decision to unbundle IBM was vital for the development of the software industry. From 1969, the independent software industry experienced remarkable growth. Software companies were able to compete with the computer leader—IBM. Professors Martin Campbell-Kelly, William F. Aspray, Jeffrey R. Yost, Honghong Tinn & Gerardo Con Díaz noted that “the [IBM] unbundling decision accelerated the process by transforming almost overnight the common perception of software from free good a tradable commodity.” For instance, they reported that in the American insurance industry, the IBM unbundling was “the major event triggering an explosion of software firms and software packages for the life insurance industry.” Many companies started flourishing. In the 1980s, a start-up called Microsoft developed operating systems for personal computers becoming IBM’s key supplier. No one can deny that after the IBM unbundling decision the software industry has grown.

Enter Microsoft

In the 1990s, Microsoft held over 90% of the world’s market of personal computers, becoming the new antitrust target in the computer industry. Many antitrust scholars referred to the Microsoft saga, due to the complexity of the U.S. Microsoft antitrust cases. Antitrust remedies consisted of behavioral actions, including mandated disclosure of certain protocols and software program interfaces, as well as limitations on some contracting practices. It also recognized computer manufacturers’ rights to restrict the visibility of certain Windows features in new personal computers. According to the DOJ, competition in middleware and PC operating systems markets significantly increased thanks to the antitrust intervention. For instance, it was noted Microsoft’s Internet Explorer faces increased competition “from web browsers such as Mozilla’s Firefox, Opera, and Apple’s Safari.” Furthermore, “[t]he decision by Dell and Lenovo to offer the option of computers pre-loaded with a Linux operating system rather than Windows” also had a positive impact on competition.

Intel

Another important U.S. antitrust case in the computer industry was Intel. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission filed a complaint accusing the CPU market leader of having engaged in a pattern of anticompetitive practices to maintain its monopoly on x86 CPUs and create a monopoly in the market for graphic processing units. In the consent decision reached with the FTC, Intel agreed to implement important remedies, including modifying some critical intellectual property agreements with three of Intel’s main competitors. Intel also agreed to maintain its key interface for at least six years to not limit the performance of competitors. The interoperability remedy was critical for manufacturers of complementary products and worth mentioning in the antitrust role in driving innovation. This case shows how a remedy like interoperability can be effectively implemented through a case-by-case ex post antitrust approach by tailoring this remedy to the specific needs and situation rather than ex ante regulation like the European Digital Markets Act (DMA).

Today’s Big Tech Landscape

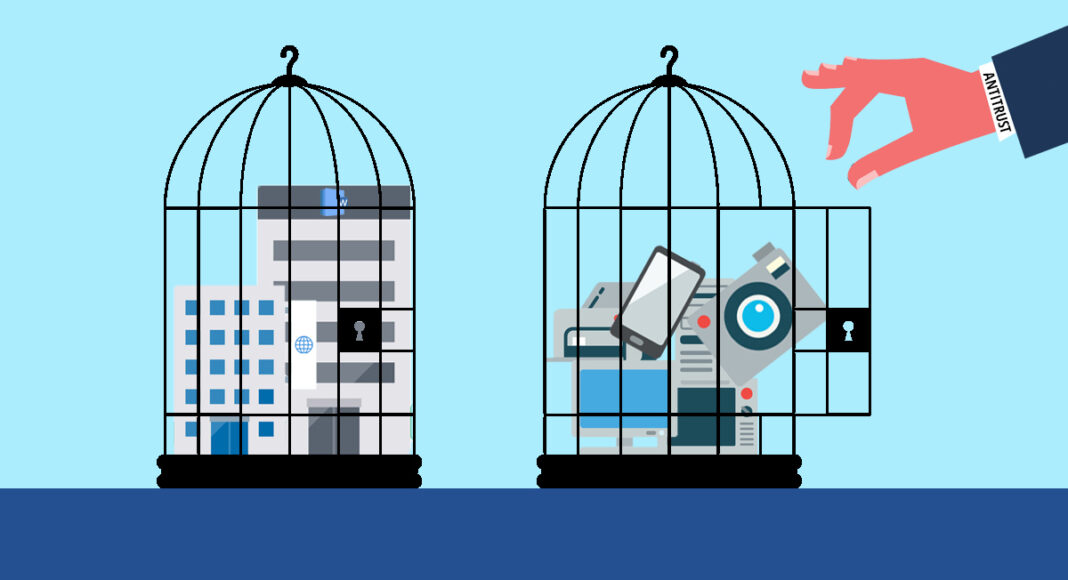

Presently large digital companies, known as Big Tech, are in the crosshairs of regulators and Congress for alleged monopolistic conduct. Antitrust lawsuits, and government and legislative interventions worldwide against Big Tech, are hard to count. Keeping track of their developments has become challenging. A recent study published in this journal identified “100-plus antitrust cases” only considering Google in 23 jurisdictions.

The U.S. has often been criticized for being lax compared to EU antitrust enforcers in dealing with Big Tech’s power. But innovation does not seem to be a hallmark of EU companies. In the U.S., Alexander Bell invented and patented the telephone before founding what was later called AT&T. It was at AT&T that other game-changer technologies, such as the transistor and Unix operating system, were also invented. IBM, Microsoft, Google are only three other examples of U.S. tech companies which changed the computer industry forever by setting the tone for the present digital economy. This raises the question of whether U.S. antitrust enforcement action played a prominent role in the innovation process which led to breakthrough technologies flourishing especially in the computer industry. It also begs the question “why do we see less innovation on the other side of the Atlantic?”

The economist Reuven Brenner argued that “every business competes by betting on new ideas,” and he is probably right. Although innovation is a broad term, which might be difficult to precisely define, “new ideas” are fundamental in the innovation process. However, it is hard to think we can either regulate or predict new ideas effectively. Judge Richard A. Posner wisely observed that antitrust intervention might be slow in comparison to the rapidity of innovation. However, the computer industry would certainly look different today without any antitrust intervention. Although antitrust in the U.S. is not the cure for any economic diseases, more than a century of experience in enforcing this law shows some important evidence. Antitrust law often paved the path of innovation toward the creation of new markets and development of new technologies, which according to economists, such as Joseph Schumpeter, is what competition is all about.

History tells us that antitrust enforcers can be crucial in maintaining the delicate balance between controlling the actions of large players without compromising their incentives to innovate through consent antitrust measures. In each situation, the company’s role in shaping antitrust remedies were fundamental. And in retrospect, as we look closely at the computer industry, it was the U.S. antitrust approach, albeit not perfect, that seems to have done its job well.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.