Competition authorities and analysts are increasingly focused on the impact of mergers and acquisitions on worker welfare. Using a novel dataset on Canadian firms and workers, David Arnold, Kevin Milligan, Terry S. Moon and Amirhossein Tavakoli test the empirical validity of several theories on how M&A may help or harm workers.

Conventional analysis of corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A) assesses the impact of a merger or acquisition based on how the M&A affects the competitiveness of markets. Will prices rise? Will scale or scope efficiency gains materialize? How does the M&A affect firms and consumers? More recently, many analysts have expressed concern about the labor market impact of M&A. Workers are not just inputs to production processes, but also human beings whose welfare might concern policymakers. How do corporate M&A affect workers and how large is the impact?

M&A activities could impact workers through three main channels. First, if there are fewer firms operating in a market, there will be less product market competition. Fewer firms in a market can change prices, sales margins, or the efficiency of production. These impacts could be passed through to workers. For example, if profits increase, workers may be able to negotiate for a share of that higher profit. Second, and conversely, M&A could lead to less competition in the market for workers because there are fewer firms hiring labor. When there are few employers hiring workers, the employers could exercise their monopsony power, leading to lower wages overall. The third channel is through job separations. If workers are laid off or leave a job following an M&A, they must find a new job which might have lower pay than their previous job.

In our new research, we investigate these different ways in which M&A affect workers using a large sample of corporate M&A in Canada. We bring new evidence to the debate because our data allows us to link data on worker earnings to the firms they work for, seeing the firms’ sales, profit margins, financing structure, and employment. This kind of worker-firm-linked data is crucial for making progress on understanding the impact of corporate M&A on workers because we can see which of the above channels is driving any changes in worker pay.

Our data starts with all firms and workers in Canada from 2001 to 2017. We then pick out the firms that went through a corporate M&A, whether they’re public or private so long as they have at least 10 workers. For each firm going through an M&A, we try to find a comparable firm that did not go through an M&A to act as a control group, using data on a firm’s age, payroll, and revenue. We show that this matched control group looked very similar to the M&A firms in the years leading up to the M&A event, giving us confidence that comparing the M&A firms and the control group firms after the M&A event should be informative about the impact of M&A.

We first take a look at what happens to the firms. The firms that are merged or acquired in the M&A tend to shrink while the acquiring firms grow. This is true for employment headcounts, total payroll, and revenue. But what about profit margins and markups? We find profit margins for both the acquirers and the remaining parts of a target firm fall, while markups don’t change much at all. This evidence is not great news for the idea that corporate M&A improve the efficiency of the economy through more efficient production or that M&A allow firms to charge higher prices and earn more profit. But this evidence also means that changes in profitability are unlikely to be a leading channel of the impact of M&A on workers.

What about the monopsony story—do typical M&A have a big enough impact on labor market concentration to matter? Previous evidence shows that when a merger happens in a market that is already pretty concentrated, the increase in monopsony power can hurt workers. In our new research though, we find almost no change in labor market concentration for the typical M&A. So, this monopsony channel is unlikely to drive worker outcomes in our data. The monopsony power of hiring firms might matter in some labor markets, but it’s not a key driver of worker outcomes following corporate M&A.

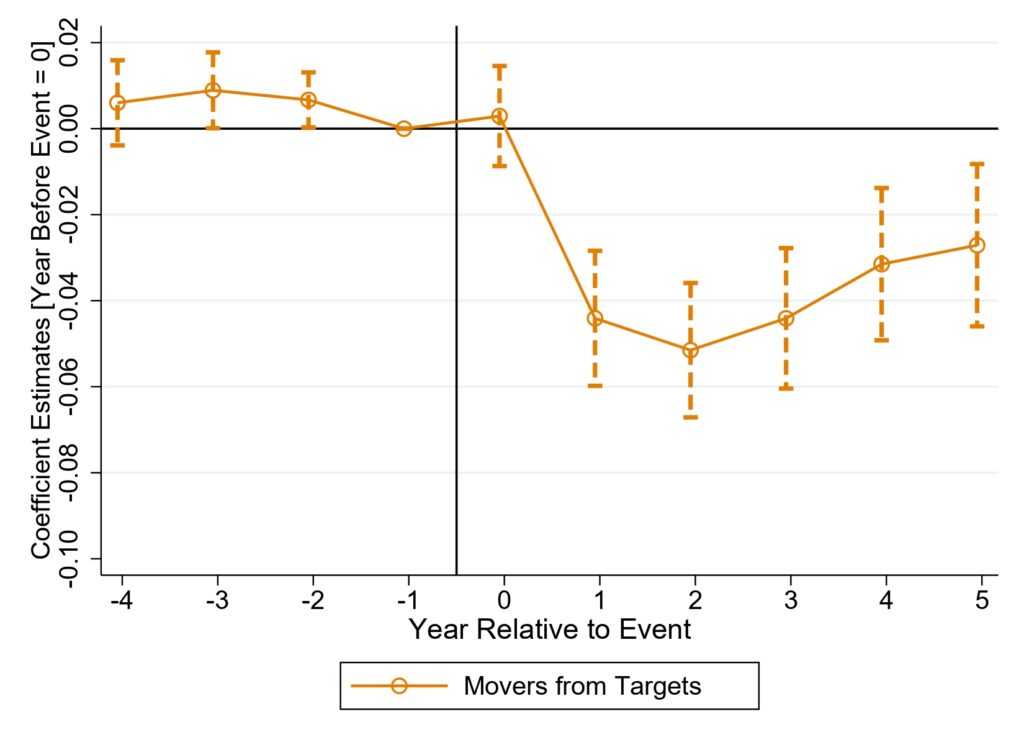

The third channel we look at is job displacement. Who is laid off or changes jobs following M&A and what happens to them? In our data, we can follow individual workers before and after M&A events. For those working in the acquiring firms, there’s no big change in employment or earnings. But for those working in a firm that was taken over, earnings go down and that earnings drop is mostly driven by job separations. As shown in Figure 1, for workers switching firms after an M&A, earnings are down about 4 percent on average.

Figure 1: Earnings for Workers Moving From Target Firms

Note: Figure shows earnings drop for workers moving from target firms within the first two years after the M&A event.

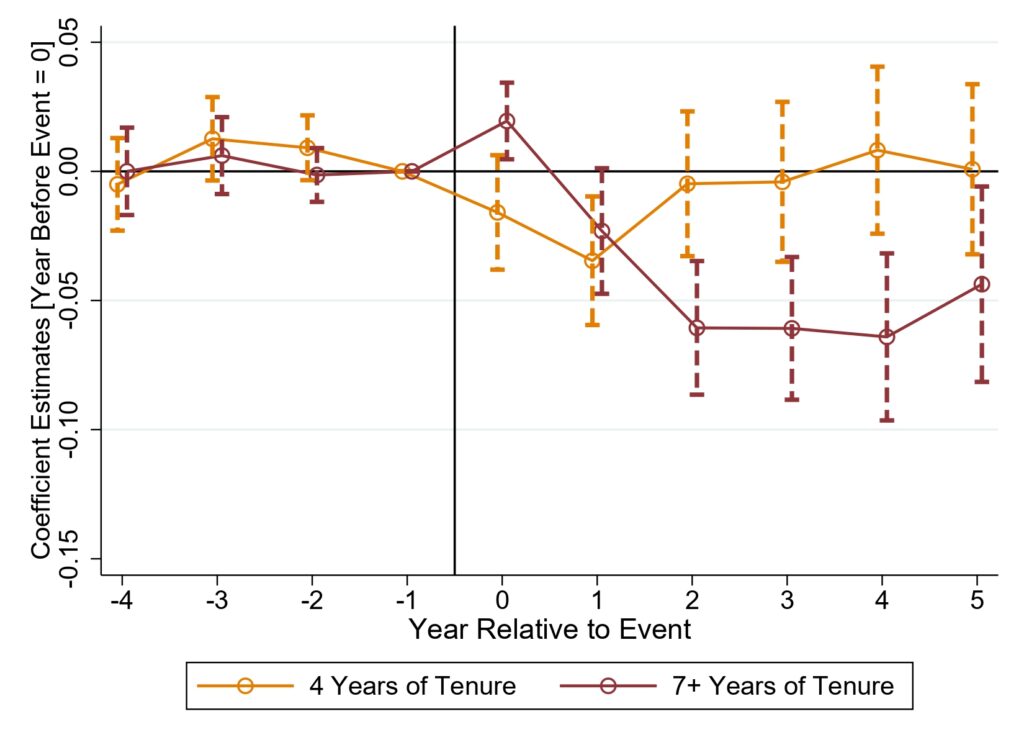

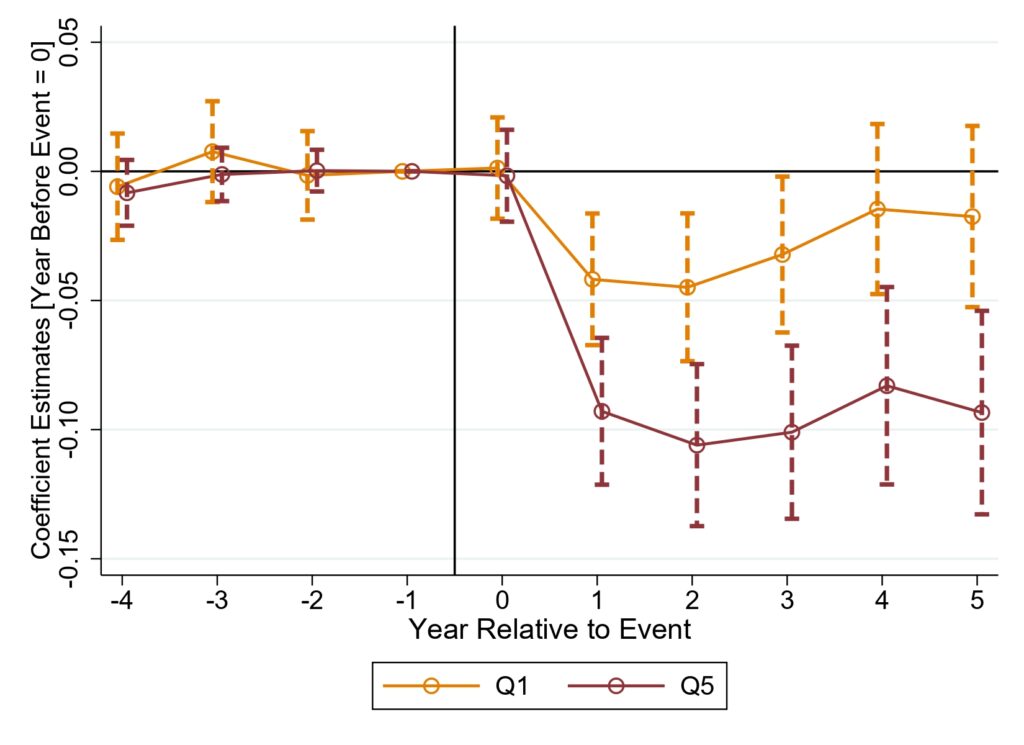

We’re able to dig even deeper into why earnings drop. It turns out that the firms where workers go to once separated from their previous firm post-M&A are on average larger firms with better pay. But, as a new hire who must acclimate to a new-if-comparable role, the value of the match –i.e. the employee’s productivity–with the new firm is lower than with their old firm, and this worse match drives the overall pay down. The workers suffering the largest earnings drops tend to be those who have spent a longer time at the old firm (Figure 2 – left) and also those with higher pay (Figure 2 – right). If these workers were receiving higher pay because they were very productive at their old firms, then the loss of this employer-employee match through the M&A destroys something valuable. On the other hand, if the post-M&A firm can operate efficiently without as many workers then society might be better off with that extra labor allocated to new firms where those workers can produce needed output.

Figure 2: Earnings for Workers Moving From Target Firms by Worker Tenure and Within-Firm Earnings Distribution

Note: Figure on the left shows earnings drop for workers moving from target firms within the first two years after the M&A event, separately for those who had 4 years of tenure compared to those with 7 or more years of tenure. Figure on the right shows earnings drop for workers moving from target firms within the first two years after the M&A event, separately for those in the top 20% of earners (Q1) vs those in the bottom 20% (Q5).

Our findings deliver two lessons for competition policy. First, we don’t find that increasing corporate competition driven by M&A is important for workers either through concentrating the market for the products the workers produce, which would in theory increase worker wages, or through concentrating the labor market, which would in theory decrease their wages. Higher concentration in product markets and monopsony power of employers may matter for overall welfare, but typical M&A don’t change these factors enough to help or hurt workers. Second, worker earnings are hurt by M&A because of job displacement; people switch jobs or are laid off in target firms after an M&A. If competition policy puts weight on the welfare of workers, this could become a consideration for judging the social benefit or cost of a potential M&A. But the efficiency impact of these M&A-driven job transitions depends on whether the higher pay at the old firm reflected higher productivity or was itself a source of inefficiency that the M&A was able to eliminate.

Overall, it’s up to policymakers to decide how much competition law should consider the outcomes of workers in deliberations on allowing a particular M&A to go forward. Our evidence shows that the impact of corporate M&A on workers is mostly through the channel of job displacement and not through the channels of product market or labor market concentration.

Authors’ disclosure: This research is funded through a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of ProMarket, the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.