In new research, Matthew C. Ringgenberg, Chong Shu, and Ingrid M. Werner ask if academic research exhibits political slants. They develop a new measure of the political slant of research and study how it varies by discipline, demographics, and the political party of the sitting United States president. Finally, they show that their measure is related to the researchers’ personal political ideology, suggestive of an ideological echo chamber in social science research.

In our new paper, “The Politics of Academic Research,” we introduce a methodology to gauge the political leanings of academic research within the social sciences in the United States. Our demand-based measure is based on the political leanings of public policy think tanks and how they cite academic research papers and their authors. Think tank reports generally cite research that agrees with their political interests, as we elaborate below. We find that economics and political science research leans left, while finance and accounting research leans right. Moreover, this result persists even after controlling for the topic. For example, research on executive compensation is more likely to be cited by right-leaning think tanks if it is conducted by finance professors and more likely to be cited by left-leaning think tanks if conducted by economics professors. We also find that the political slant of research is correlated with the research authors’ Ph.D. institution, and research conducted outside universities at government agencies and the Federal Reserve appears to cater to the political party of the United States president in office at the time the research is conducted. Finally, our demand-based measure of the political slant of research is related to the researchers’ political ideology, as reflected in their political donations.

It is critical to understand whether politics impacts the findings in academic research. Consumers of academic research read an academic article because they want to learn about a particular topic, and they are likely to update their beliefs in a different way if they know that research is influenced by the authors’ political leanings. The stakes are particularly high for social science research, as it exerts a strong influence on policy decisions ranging from school choice at the local level to fiscal and monetary policy at the national level.

While several papers examine the political views of academic researchers based on voter registration choices, petition signatures, and political donations, the mere fact that a researcher has political beliefs does not necessarily mean their research is biased. Everyone—including academic researchers—has political beliefs, but it remains unclear whether these beliefs actually influence research findings. Empirically, it is difficult to ascertain whether personal beliefs influence the content and use of academic research. So, to assess the political slant of academic research, we avoid evaluating the political ideologies of the researchers themselves and instead investigate how often think tanks of varying political ideologies cite these researchers and their work. We also do not make any claims about whether a political leaning on a particular topic is closer to the “truth.”

Consider two well-known economists: Paul Krugman and John Cochrane. Among the papers by Krugman available on the Social Science Research Network (SSRN), 92% of think tank citations of Krugman’s papers come from liberal ones. In contrast, only 27% of citations of Cochrane’s papers are from liberal think tanks. Implicitly, our methodology assumes that think tanks are more likely to cite findings with which they politically agree. While it is certainly possible that an article can cite a paper negatively—for instance, to refute it—we find such instances are very rare. As a result, our methodology suggests that the findings in Krugman’s research are left-leaning while the findings in Cochrane’s research are more right-leaning. We emphasize that this methodology does not indicate that Krugman is necessarily left-leaning in his political beliefs, nor does it imply that the findings of either researcher are not “objective.”

We classify think tanks as either liberal or conservative based on how often research from these think tanks is cited in speeches by members of Congress. Instead of limiting our definition of liberal or conservative to a binary classification, we employ a measure introduced by Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal (1985) that ranges from -1 to +1 called the NOMINATE measure. This measure assigns a continuous score to each congressperson based on their voting record. A more negative score indicates a more progressive lawmaker; for example, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders (with a NOMINATE score of -0.56) is more ideologically liberal than West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin (with a NOMINATE score of -0.06). We calculate an ideological score for each think tank by averaging the NOMINATE scores of the speeches by congress members that cite the think tank. For instance, the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation has a high NOMINATE score of 0.26, while the progressive think tank the Economic Policy Institute has a low NOMINATE score of -0.36.

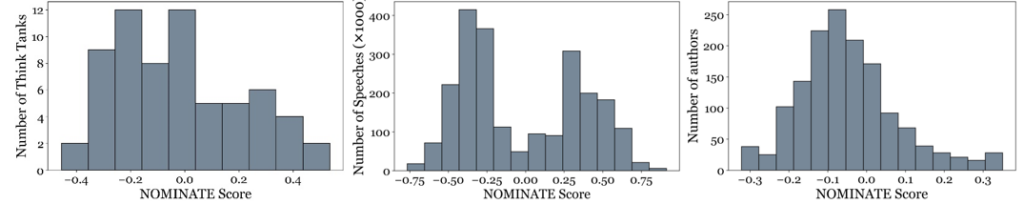

To summarize our methodology, we begin with the political ideologies of members of Congress. We then evaluate the ideological leanings of various think tanks based on how frequently they are cited in Congressional speeches from the 97th through the 114th Congress. Finally, we measure the relative political slant of more than 600,000 academic papers by examining how often they are cited in more than 59,000 think tank reports. Figure 1 below illustrates the distribution of political ideologies. As expected, the political ideologies of members of Congress (middle panel) are bimodal due to the influence of two major political parties. However, the distribution of economists’ ideologies is single-peaked (right panel). This suggests that economists are not clearly sorted into a left-right divide. However, the thick tails on each side of the distribution indicate the presence of economists whose research is overwhelmingly cited by think tanks on one side of the political spectrum.

Figure 1: Distribution of NOMINATE SCORES

Are Economics Professors Liberal?

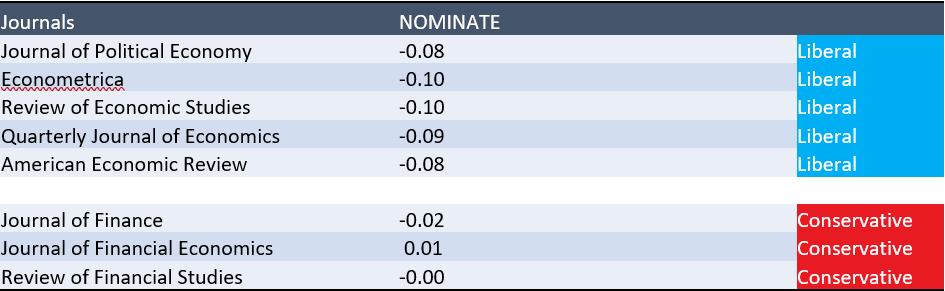

We use our method to examine the political slant of research in different disciplines based on the papers published in the top journals in accounting, economics, finance, political science, and sociology. Table 1, below, summarizes our findings for several of the journals in economics and finance in our sample: the first five rows show that papers published in the top economics journals are cited more by liberal think tanks, while the last three rows show that papers published in top finance journals are cited more by conservative think tanks. This pattern is also evident in the other economic and finance journals in our sample, with their scores detailed within the paper. We also find that economics journals are cited more than research in other social science disciplines, consistent with T.V. Maher et al. (2020), and we find that think tanks are more likely to rely on academic research in recent years.

Table 1

Of course, it is possible that finance professors write about topics that are more likely to interest conservative think tanks, while economics professors write about topics that are more likely to interest liberal think tanks. But even after controlling for the topic of each article using Journal of Economic Literature (JEL) topic codes, we find the results hold.

Ideology of Demand and Demographics

Do differences in the political slant of research have an explanation beyond academic discipline? Can they be explained by the researchers’ demographics, such as gender or their Ph.D.-granting institutions, or other factors such as if the researcher works in academia or for banks or government agencies?

Gender

Our results show that research conducted by women is more likely to be cited by a left-leaning think tank than research conducted by men: liberal think tanks cite male authors 7% less often than female authors. This evidence is consistent with recent survey evidence (e.g., Ann Mari May et al. (2014), Harry van Dalen (2019), and Ann Mari May et al. (2018)). However, whereas surveys compare the ideological views of female to male researchers, they do not show whether the research produced by women has systematically different political leanings than the research produced by men. Our findings show it does.

Ph.D. Training

We also find that the political slant of researcher output is related to the ideological slant of the institution where the researcher obtained their Ph.D., controlling for gender and other factors. For example, a graduate from the University of Southern California’s economics department is more than twice as likely to be cited by a left-leaning think tank compared to the average researcher, while a graduate from the George Mason University’s economics department is associated with a sizable shift to the right. Of course, we are careful to note that these results could be due to a selection effect (e.g., liberal students choose to study in liberal departments) or a treatment effect (students inherit their views from the department at which they study). We do not investigate these possible relationships further, and future research should explore the mechanism driving these results.

Employer

In addition, we find that research at government agencies and regional Federal Reserve banks is significantly more likely to slant towards the political party of the current U.S. president, when compared to research conducted by academics at universities. However, again, we are careful to note that the results could be driven by a variety of selection or treatment effects, and these explanations are difficult to disentangle.

The Ideological Demand and Supply of Research

Finally, we attempt to answer if the political slant of social science research might reflect the political ideologies of the individual researchers rather than simply share an affinity with the political agendas of public policy think tanks. Specifically, is it the case that right-leaning think tanks cite papers written by right-leaning scholars, and left-leaning think tanks cite papers by left-leaning scholars? We find that it is.

We examine the political donations of 2,675 researchers who have being cited by think tanks, and find they are related to the average ideological score of the researcher’s papers. For researchers that donate to one or more parties during our sample period, we find that a scholar who donates to the Republican Party is 16% less likely to be cited by a liberal thank. When we include all researchers in our sample (a total of 16,749), including those who have never donated, the difference shrinks to 10%.

Overall, the evidence shows that the political slant of research is not merely a result of public policy think tanks seeking out results that confirm their ideological positions (the demand side), but that the political beliefs of individual researchers align with the content of the articles they write (the supply side). In other words, there appears to be an echo chamber effect in social science research: left-leaning politicians cite left-leaning think tanks who cite left-leaning scholars who support left-leaning politicians, and right-leaning politicians cite right-leaning think tanks who cite right-leaning scholars who support right-leaning politicians. Social science research has an outsized influence on public policy. The possible existence of an echo chamber between researchers, think tanks, and policymakers deserves further consideration in our highly polarized age.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.