Capital markets are central to capitalism and the functioning of the US economy. Yet, short-selling, an integral part of price discovery in capital markets, has been blamed as a contributor to the recent banking crisis. Lawmakers and interest groups have labeled short sellers opportunists who prey on small investors and the public without justification. The authors shed light on this debate and question the merit of the allegations.

March through May of 2023 will be remembered in US banking history as period of confusion and reflection by bank analysts who failed to examine the basic financial reports filed by a major bank with the SEC, by regulators and supervisors who found themselves in indefensible positions in delivering their mandates, and by investors and the public who lost billions of dollars and wondered if they need to save the banking industry again with their limited resources.

Silicon Valley Bank, which had $212 billion in total assets and $312 billion in total client funds as of the end of 2022, closed on March 10, 2023. Signature Bank, listed as the 19th largest bank in the United States by S&P Global in December 2022, closed on March 12, 2023. First Republic Bank, which was the 14th largest U.S. bank with an enterprise value of more than $19 billion in 2020, became the third large, publicly traded bank to close its doors on May 1, 2023.

In response to these closures, Harrison Miller reported on May 5th that the American Bankers’ Association (ABA) had called for a probe into short sellers profiting off of the bank crisis and had stated that the short sellers’ trades were “disconnected from the underlying financial realities.” The president of the ABA said that “the harm caused by short selling that runs counter to economic fundamentals ultimately falls on small investors, who see value destroyed by others’ predatory behavior.”

Chris Matthews reports that on May 8th, Mark Fitzgibbon and Stephen Scouten, who cover the sector for Piper Sandler, wrote to clients that “regional bank turmoil has increased at a pace that is disconnected from the reality of fundamentals.” Matthews further notes that the gentlemen “argued that the Securities and Exchange Commission should institute a ban on short sales of regional bank stocks, to give Congress time to agree on a plan that raises deposit insurance limits and stop any budding bank runs that could be inspired by weakness in regional banks.” Finally, Chris Matthews writes on May 16th that “Republican Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio has requested that bank regulators investigate whether the run on deposits at Silicon Valley Bank were orchestrated by short sellers seeking to profit from the bank’s failure.”

At the very least, experienced staff at the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) were opposed to the implementation of a short sale ban. On May 5th Bloomberg reported that Anne-Marie Kelley, a former longtime senior SEC official and adviser to multiple chairs, stated that “prior experience with a short sale ban in 2008 showed it was counterproductive, fueled panic, and actually undermined confidence in the financial sector, so we need to proceed extraordinarily cautiously and judiciously in order not to worsen problems in the banking sector.” On May 8th FOX Business reported that “if Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Gary Gensler wants to ban short selling of regional bank stocks, he will have to do it over the objections of the agency’s career staffers.”

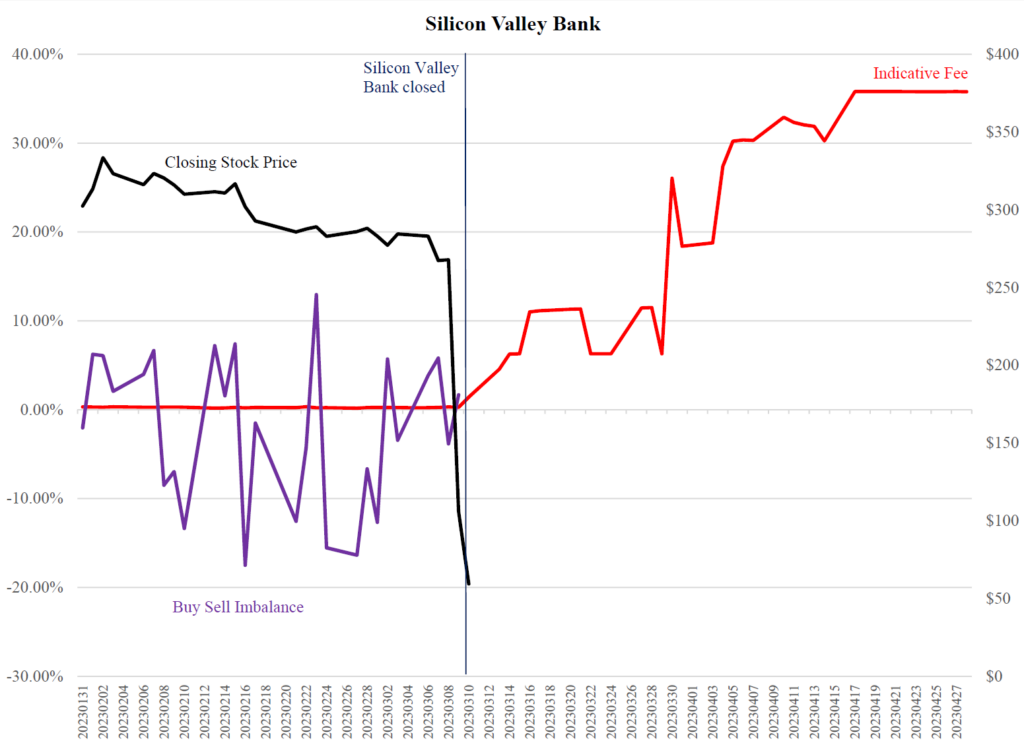

The graph presented in Figure 1 illustrates that (short) selling is not associated with the decline in Silicon Valley Bank’s stock price prior to its closure. We use a black line to plot the closing prices for Silicon Valley Bank (obtained from CRSP) in the days prior to its closure. The red line is a plot of the daily indicative annualized fee paid by investors who borrowed shares of Silicon Valley Bank to short before and after the bank’s closure. We obtain these data from IHS Markit.

The graph clearly shows that borrowing costs only became elevated, indicating an increased demand to short Silicon Valley Bank’s shares, after the bank’s stock price fell by 50% on March 10th (presumably in response to the announcement that the bank was closing).

Finally, we use a purple line to plot the daily buy/sell imbalance for Silicon Valley Bank’s stock in the days leading up to March 10th using data provided by WRDS. The daily buy/sell imbalance is computed by dividing the difference in buy and sell trading volume by the sum of buy and sell trading volume and the measure does not differentiate between long and short sales.

As illustrated in the graph, in the days prior to Silicon Valley Bank’s closure, daily imbalances were less than 5% and were both positive and negative. In other words, it does not appear that imbalanced sales are responsible for the decline in Silicon Valley’s stock price.

Figure 1.

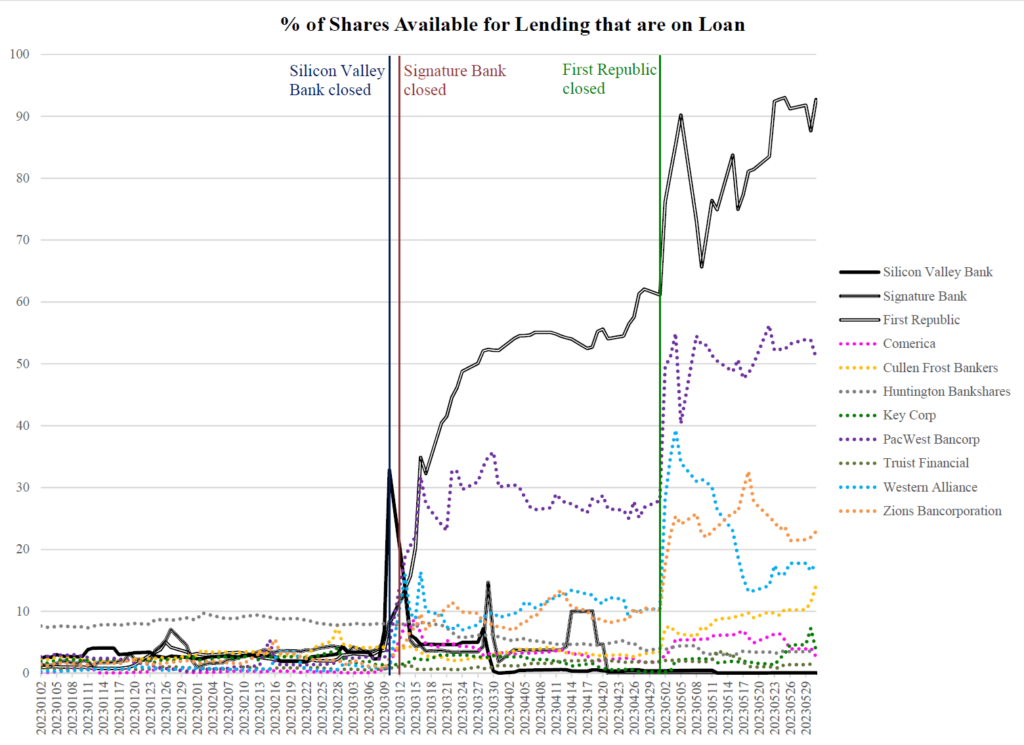

Another way to examine the activity of short sellers around the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic is to examine the percentage of the shares that are available for lending that have been borrowed to initiate short positions (e.g., the utilization rate). Schultz (2020) finds the median utilization rate for stocks in the IHS Markit database is 8.76%, the interquartile range is from 2.40% to 25.02%, and the 95th percentile utilization rate is 69.37%.

We identify eight additional regional banks that are mentioned in articles as potential targets of short sellers. Figure 2 contains a plot of the utilization rates for the three closed banks and the eight additional ‘control’ banks from March 2nd through May 30th of 2023. The data are obtained from IHS Markit.

In the weeks before Silicon Valley Bank’s closure on March 10th, the bank with the highest utilization rate was Truist Financial, whose utilization rate was between 7% and 10%. Interestingly, the utilization rate for Truist falls after Silicon Valley Bank’s closure. Silicon Valley Bank’s utilization rate, which was less than 7% in the weeks prior to the bank’s closure, rises from 7% on March 9th to 33% on March 10th and then falls precipitously over the next several days.

At its peak, Signature Bank’s utilization rate was well below the 75th percentile utilization rate documented in Schultz (2020). Signature Bank’s utilization rate, which averaged 2.9% between January 2nd and March 8th, rises to 5.4% on March 9th, 8.25% on March 10th, and peaks at 13.17% on March 13th. With the exception of March 29th, Signature Bank’s utilization rate remained below 10% for the remainder of March and throughout April. Thus, Signature Bank’s utilization rate never exceeded the median utilization rate documented in Schultz (2020).

Figure 2.

Of the three banks that closed, First Republic had the highest level of short selling activity. As seen in Figure 2, First Republic’s utilization rate peaked at 62% in the days prior to its closure. After First Republic closed, the utilization rate for shares of the bank rose to as high as 93%. Thus, in the days prior to and following its closure, the utilization rate for shares of First Republic was around the 95th percentile utilization rate documented by Schultz (2020). While shares of First Republic were available to short prior to the bank’s closure, the indicative fee (e.g., the cost of borrowing shares) was high. The IHS Market dataset reveal that the indicative fee for First Republic rose from 19.8% on April 24th to 51.2% on May 1st. The indicative fee was 88.1% on May 2nd and peaked at 184.41% on May 3rd.

Following the closure of Silicon Valley Bank, PacWest Bancorp was the only control bank whose utilization rate rose above the median utilization rate documented in Schultz (2020). Zions Bancorporation, Western Alliance, and PacWest Bancorp each had utilization rates that exceeded 25% on one or more days following the closure of First Republic. However, throughout the sample period from January 1st through May 30th, the daily utilization rate for each of the eight control banks remained below the 75th percentile utilization rate documented in Schultz (2020) and the maximum indicative fee for these banks during the sample period was 17.93% (the indicative fee for PacWest Bancorp on May 15th).

To summarize, utilization around the closing of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank is broadly consistent with short sellers trading on information and not with short sellers attempting to manipulate prices. Utilization is small, less than 10%, for the banks that went under and the other regional banks before Silicon Valley Bank closed. There was no significant shorting of any of these banks whatsoever before the first bank failure.

Right after Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were closed, utilization increased sharply for some, but not all of the other banks. This is consistent with short sellers trading on new information. Utilization did not increase over the next couple weeks, as it would if short sellers were trying to manipulate prices. For each of the banks, far more shares were available to borrow and short than were actually shorted. The exception to this is First Republic, which saw increasing utilization until it was seized by regulators. Short sellers correctly anticipated its problems. When First Republic closed, utilization immediately increased for other banks, but did not continue to increase as we might expect with manipulative short selling.

Manipulative short selling attempts to profit from short selling an asset that is not overpriced. Even without the costs and risks of short selling, this is not easy to do. Suppose the short succeeds in driving down the price of a stock by selling shares with a downward sloping demand curve. Ultimately, the short seller needs to repurchase the shares at a lower price. If the stock price fell by $10 as a result of selling 500,000 shares, how much will the price rise as the short seller attempts to repurchase 500,000 shares? Any profit from shorting is likely to disappear when short sellers attempt to close positions.

This leaves two ways to profit from manipulative short selling. One is to mislead investors with long positions into thinking shares are overpriced. Short sellers have been accused of doing this by spreading rumors or false information. But, as Ljungqvist and Qian (2016) show, it takes months for share prices to fully adjust to unfavorable information released by short sellers that is true. Over this time, the market should be able to determine if information is false. The second way to profit from manipulative short selling with banks is to drive down a bank’s stock price and in so doing spur a run on the bank’s unsecured deposits. This requires significant pressure on the stock price that may be difficult to maintain.

Short selling in general is a costly and risky investment strategy, even when the short seller correctly identifies an overpriced security. Short sellers have to borrow shares. It may be difficult to borrow shares in stocks with small or moderate numbers of shares outstanding (like regional banks). As we have seen, if there is a lot of interest in shorting, borrowing fees may be high. A number of studies have shown that heavily shorted stocks remain overpriced for many months, so short sellers pay high fees for a long time. During this time, the short seller may be forced to close a position if the stock lender recalls the shares he has borrowed.

Short selling is costly and risky when the short seller is right, but it is even riskier and more difficult to profit by manipulating prices through short sales. The short still has to pay the fees and bears the risk of their shares being recalled. In addition, as Lamont (2012) points out, firms have a number of ways to fight manipulative short selling. They can request an investigation by the SEC or the exchange. They can file lawsuits. They can issue press releases to debunk short sellers’ claims. Investigations and lawsuits are especially likely to bear fruit if the short seller is engaged in manipulative shorting.

To sum up, we tried to examine if there was a pattern in the data that could speak to manipulative or opportunistic behavior on the part of short sellers that contributed to the current banking crisis. We did not observe any evidence. We encourage others to examine the data as well. At the outset of any crisis, the public, law makers and interest groups speculate what caused the crisis. It is unwise to blame a group without any basis, in this case the short sellers, and potentially divert society’s resources.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.