There is a significant ongoing debate in the United States on the merits of plurality voting (how most American elections are conducted) and how alternatives may produce more representative results. In new research, academics from The Center for Election Science, the Paris School of Economics, and the University of Strasbourg use the 2016 U.S. presidential election as a case study to discuss several alternative voting methods, their benefits, and their drawbacks.

In 2016, the United States saw a heated and highly polarized presidential election with candidates that deeply divided the nation. Amidst the continuing debates and controversies surrounding the election, one crucial question arises: Could the outcome have been different if the U.S. had used an alternative voting system?

In our recent study, we compared four alternative voting methods—plurality, approval, ranked-choice, and range voting—against an honest assessment measure that asked survey participants about their desire to see each candidate elected within the context of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Our findings offer a fresh perspective on the impact of voting systems.

The Study: A Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Voting Methods

To gain a deeper understanding of the impact of voting systems on election outcomes and to uncover the electorate’s true preferences, we conducted an extensive study focusing on the 2016 U.S. presidential election. By examining the effects of different voting methods, we aimed to determine if the choice of a voting system could lead to different outcomes and representations of the candidates.

Our study involved a representative sample of more than 2,000 respondents who participated in a poll designed to assess their preferences using four alternative voting methods. This poll took place immediately before the 2016 election. Each of these methods is unique in its own way. Here’s how they work:

Plurality voting (the method most American elections use) lets voters pick just one candidate. The candidate with the most votes wins.

Approval voting lets voters pick all the candidates they want—one, two, or however many—and no ranking is necessary. Again, the candidate with the most votes wins.

Ranked-choice voting (also known as instant runoff voting or RCV) requires voters to rank candidates in order of preference, with the candidate having the fewest first-choice votes being eliminated in each round until a candidate has more than half the remaining first-choice votes. Many in-use ballot designs (particularly at the time of this study) limit the rankings to three, and so this study limited the rankings to three as well.

Range voting (also called score voting) allows voters to assign a score to each candidate, with the highest-scoring candidate winning the election. Our scale used a 0-5, inclusive, range.

In addition to the alternative voting methods, we also asked respondents to provide an honest assessment of each candidate (also using a 0-5, inclusive, scale), indicating the respondent’s honest desire to have that candidate elected. We used this measure of voters’ opinions before the 2016 U.S. presidential election to assess the accuracy of each voting method in capturing voter preferences. To be clear, the honest assessment was not asking how respondents would have voted like the other questions. Specifically, it asked, “Regardless of their chance of being elected, how much do you honestly want the following to be elected?”

To explore the impact of the number of candidates on election outcomes, our study also included two sets of candidates: a short list and a long list. The shortlist consisted of the four candidates who actually ran in the 2016 election (Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Gary Johnson, and Jill Stein). The long list featured five additional potential candidates who might have participated in the race under different circumstances, were knocked out in the primaries, or were on only select state ballots (Bernie Sanders, Ted Cruz, Michael Bloomberg, Evan McMullin, and Darrell Castle).

Our analysis involved examining the distribution of votes under each method, identifying patterns in voter behavior (such as tactical voting or the propensity to rank candidates they didn’t like), and exploring the impact of the number of candidates on election outcomes. By comparing the results of the alternative voting methods to the honest assessment measure, we were able to determine which method best represented the true preferences of the electorate and how the choice of voting method could potentially change the outcome of the election.

Main Findings: How Voting Methods Can Shape Election Outcomes and Reflect Voter Preferences

Our study revealed several key findings about the impact of plurality voting and alternative voting methods on election outcomes and their accuracy in capturing voter preferences. The following are the most significant findings:

1. Different Voting Methods Can Pick Different Winners

The analysis of our poll data indicated that the choice of voting method can indeed lead to different election outcomes. Approval and score voting both identified Bernie Sanders as the winner (though approval voting showed a tie between Sanders and Clinton), while ranked-choice voting (RCV) and plurality voting placed Hillary Clinton as the winner. This discrepancy can be attributed to several factors that have already been identified in the literature but appear clearly in our study:

- Plurality voting and RCV are both susceptible to vote splitting, in which similar voters vote for similar candidates, thus reducing those candidates’ chances to win and instead increasing the electoral chances of a dissimilar (and potentially less preferred) candidate. Vote splitting is a well-known defect of American elections that use plurality voting. RCV is also susceptible to vote splitting of first-choice votes, which can lead to candidates being artificially eliminated early in the process, a phenomenon common in countries using plurality voting with a runoff.

- Polarizing candidates may receive more of the scattered first-choice votes within a crowded field under plurality voting and RCV, skewing the results. In contrast, methods such as approval and score voting may benefit more consensus candidates.

- When translating honest assessments into rankings, the Condorcet winner (the candidate who would win a head-to-head contest against every other candidate) may differ from the winner determined by plurality voting and RCV.

Interestingly, our findings also showed that third-party candidates Jill Stein and Gary Johnson performed significantly better in approval voting than in RCV or plurality voting, suggesting that alternative voting methods can provide a more accurate representation of support for minor party candidates. In the short-list of candidates, Stein received over 10% approval and Johnson received roughly 20% approval. See Table 1 for more details.

Table 1: Candidate scores under three voting rules

| Plurality | Plurality | Approval | Approval | Range | Range | |

| Short Set | Long Set | Short Set | Long Set | Short Set | Long Set | |

| Clinton | 47.73 | 31.38 | 50.12 | 39.78 | 2.33 | 2.32 |

| Trump | 40.52 | 27.78 | 42.01 | 33.73 | 1.89 | 2.00 |

| Sanders | 19.98 | 39.25 | 2.72 | |||

| Cruz | 9.73 | 21.46 | 1.93 | |||

| Johnson | 8.25 | 4.54 | 20.65 | 12.16 | 1.59 | 1.5 |

| Bloomberg | 4.41 | 11.65 | 1.67 | |||

| McMullin | 1.73 | 7.6 | 1.36 | |||

| Stein | 3.51 | .26 | 11.52 | 5.06 | 1.3 | 1.21 |

| Castle | .19 | 2.18 | .95 |

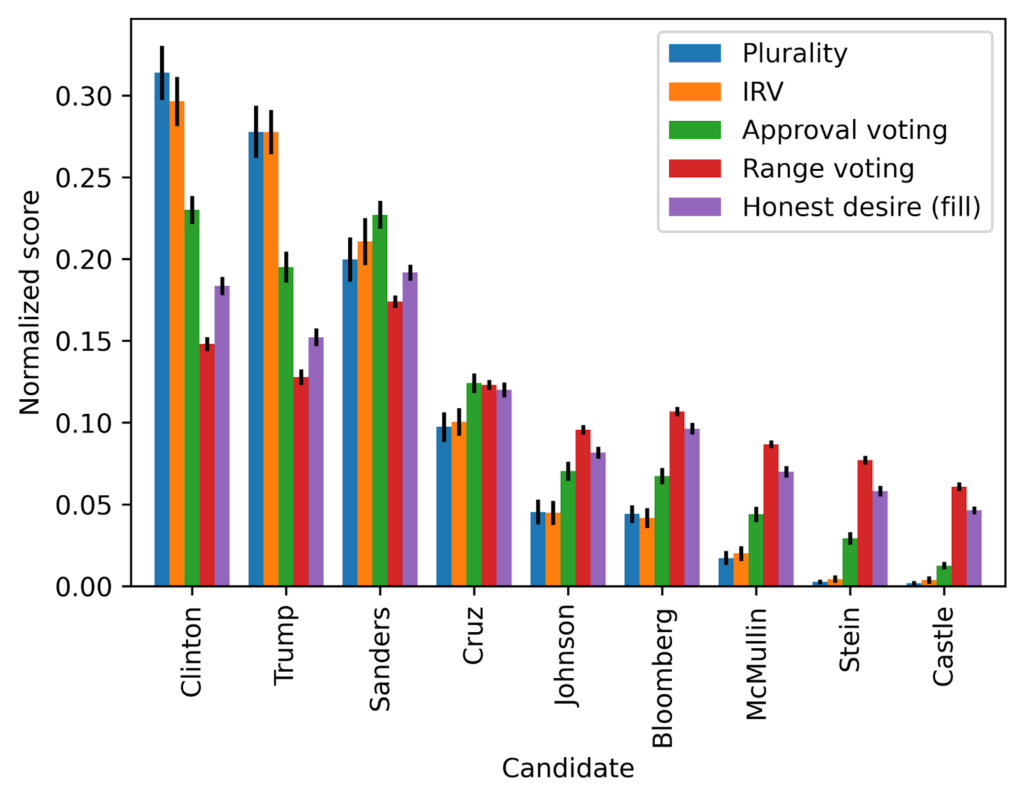

We’ve also standardized the measure of support by voting method so that they are more easily comparable, as you can see in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Normalized relative scores (with honest assessment)

2. Voting Methods Vary in Accuracy of Capturing Candidates’ Support

These different voting methods also varied in their ability to accurately capture voter preferences compared to the honest assessment control measure. Approval voting and score voting both performed well here. It may be of little surprise that score voting did a good job, as it uses the same 0-5 scale measure as the honest assessment. Approval voting’s performance can be similarly attributed to its status as a cardinal voting method, which asks voters to assign candidates independent scores rather than rank them. However, approval voting’s scoring scale is simple (zero/one) when compared to that of score voting (which uses three or more levels). RCV and plurality voting, on the other hand, were less successful in capturing the true preferences of the electorate (see Figure 1).

For example, our data revealed that some conservative voters in our sample actually liked Sanders, which was more evident under approval and score voting than RCV or plurality voting. This demonstrates the potential for alternative voting methods to uncover hidden voter preferences and provide a more accurate picture of the electorate’s true choices. See Figure 1 for the normalized honest assessment scores for each candidate.

Conclusion

Overall, our study highlights the importance of considering alternative voting methods alongside traditional plurality voting to ensure election outcomes that more closely align with the true preferences of the electorate. By exploring the impact of various voting systems on election outcomes and voter behavior, we hope to contribute to the ongoing discussion around broader electoral reform, the potential benefits of adopting alternative voting methods in the U.S., and the question of which alternative method to choose. Selecting a proper voting method for high-stakes elections is critical. The very foundation of our democracy depends on getting this reform right.

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.