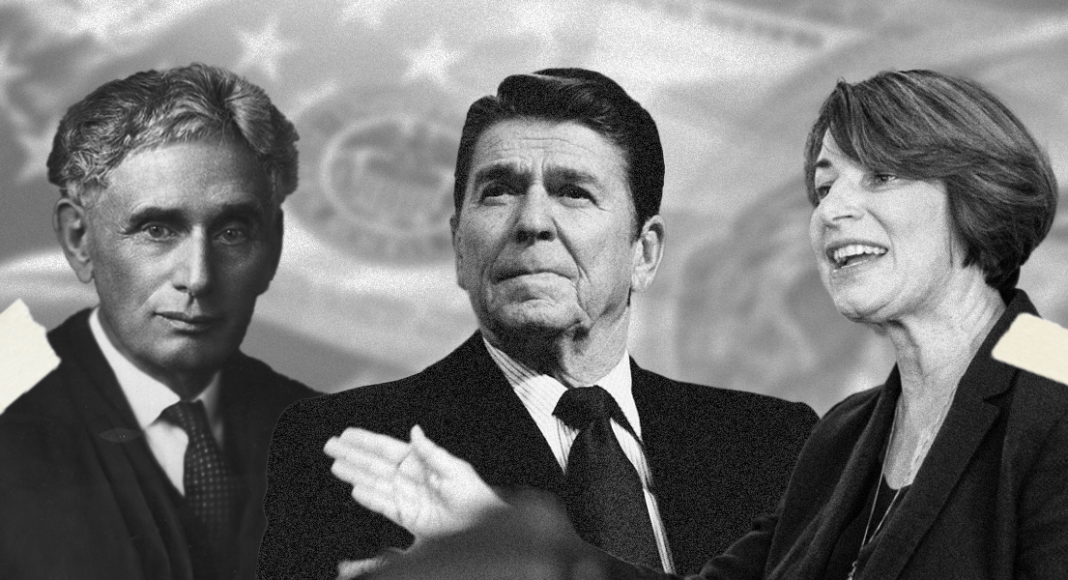

The Stigler Center’s 2023 Antitrust and Competition conference seeks to answer the question: what lays beyond the consumer welfare standard? In advance of the discussions, ProMarket is publishing a series of papers with proposed alternatives to the infamous consumer welfare standard. This piece is part of that debate.

The Stigler Center asks: Should there be an alternative to the consumer welfare standard in antitrust and if so what is the alternative?

This essay argues: that is the wrong question. There is no such thing as THE consumer welfare standard. The existential debate in US antitrust law today is: What do we mean by “anticompetitive” conduct of the sort that antitrust law should proscribe? The Supreme Court has egregiously shrunk that category. The big question is how to reverse course. This essay makes a suggestion.

I. There Is No Such Thing As THE Consumer Welfare Standard

“The consumer welfare standard” as used in common antitrust discourse is an elastic continuum, meaning its usage has evolved over the last 40 years. The modern usage began during the Reagan Revolution of 1981. The antitrust revolutionaries at the time were made up roughly of two groups: those concerned that the pro-little-guy, anti-concentration model of the Warren Court in the 1960s had taken us too far along an interventionist path and wanted to inject economic limits, and the ideological right (both conservative and libertarian) who argued that, apart from hard core cartels, antitrust was a pro-interest group intent on obstructing business.

At first, the new consensus “sun” (around which all revolved) was allocative efficiency with the assumption that business conduct was efficient and with a mandate not to condemn any conduct or transaction unless it was inefficient. This approach was anchored both in a dynamic perspective (creating a market environment that promoted the right incentives) and in an outcome perspective, total welfare.

After a decade of debate, the total welfare advocates lost the semantic debate to the consumer welfare advocates — but never gave up total welfare analysis. Meanwhile, centrists and progressives, seeing that the game had shifted from a dynamic view of preserving competition to an outcome analysis of welfare infused with efficiency presumptions, determined that they too would take ownership of “consumer welfare,” and fashioned a different concept more concerned with power and its abuse than with freedom of business. Along the way, when issues arose about treatment of innovation incentives, of hard-core buyer cartels, and of restraints in labor markets, most consumer welfare proponents at all points on the philosophical continuum would say: the standard takes care of that too.

So today, virtually everyone “owns” the so-called consumer welfare standard (and applies it to non-consumer-facing offenses) except those who advocate an antitrust vision that considers public interests. Thus, the meaning of consumer welfare as relevant to antitrust has been neutralized. The common cause is prioritizing consumer interests and rejecting non-market factors. Purporting to apply “the consumer welfare standard” to particular conduct or transactions where output effects are ambiguous, experts at different ends of the continuum come out differently because of their different premises.

Thus, the crucial debate is not about whether there is a consumer welfare standard and if antitrust should address non-market values. The crucial debate is within the big tent: what are the assumptions about markets and the State; about how well markets work, and how well antitrust intervention works, to get the best market results. Judgments, ideological beliefs, and political economy perspectives on these issues affect whether, for example, business’s acts are presumed efficient, or high concentration is suspect. They affect what is counted as “anticompetitive” and proscribed.

From these observations, we might conclude:

1) We are spending too much time debating: Should the consumer welfare standard be preserved? If not, what is the alternative?

2) Merely for truth in advertising (or debate), the name of this so-called standard should be changed because the standard is not only about consumers and it is not entirely a standard.

3) One should in any event distinguish between goals of antitrust and standards for analysis. For most of those in the big tent, a better descriptor of the goal is: “making markets work better,” or (for the non-interventionists) “removing obstructions to cure market failures.” “Protecting the competitive process” also fits well.

4) Goals are not standards. The standards for analyzing different forms of conduct and transactions to determine if they are anticompetitive are found in the caselaw, which articulates some rules and presumptions derived from the standards. These standards have been excessively influenced by laissez faire ideology insinuated by a Supreme Court majority that is not in sympathy with antitrust. This is the battleground. It is this to which I turn.

II. The Problem With Existing Standards For Analysis

The problem we face is not that we have a consumer welfare standard; especially not that we have a consumer welfare standard that, while prioritizing consumer interests, flexibly protects against market harms. The problem is that the Supreme Court has embedded laissez faire presumptions that have led to rules of law that entrench incumbents and preserve concentrated, non-competitive markets.

For example, for unilateral conduct of firms judged to be monopolies, US antitrust law has a strong principle of no duty to deal, and the caselaw tends to push exclusionary conduct into the privileged category of refusal to deal. The law has gutted the essential facility doctrine and is not likely to embrace a category of akin-to-essential facility; it has eliminated the leverage violation – except where a defendant is monopolizing a second market, and the law has little appreciation of harms from vertical restraints that clog markets and handicap meritorious rivals.

The most-needed step is to eliminate the laissez faire perspective, which is now embedded in presumptions and burdens, including what makes out a prima facie case. See, for example, the striking differences in the majority opinion of Justice Thomas and the dissenting opinion of Justice Breyer in Ohio v. American Express, and the more subtle but no less striking differences in the opinions of Judge (now Justice) Gorsuch in Novell v. Microsoft and of the court en banc in United States v. Microsoft.

III. Resetting The Compass — How To Change The Trajectory Of The Law

All avenues for changing the ingrained perspective are difficult. I mention three below, but they could all be pursued in tandem.

1. Argue The Facts And The New Business Realities Including Digital Markets

This is the approach of Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter. AAG Kanter would, for example, try to limit Trinko to the particular facts of its regulated industry context. It may be hard to escape the spirit of Trinko. Once a case reaches the Supreme Court, that spirit will control the narrative and the law for many years to come. But still, arguing the facts and the new realities is a worthy tack and should be pursued.

2. Legislation

Legislation is rightly a big consideration because the laissez faire orientation of US antitrust law at Supreme Court level cannot be changed without either removing Justices or passing legislation. There is, however, a basic problem in changing the trajectory of antitrust law by legislation, for legislation (except of the most general kind, which we already have in antitrust) is commonly black letter law, more like civil law, while antitrust law is evolutionary through the case-by-case process; heavily fact-dependent; an intermixture of fact and law, in the course of determining whether specific acts or transactions are anticompetitive.

Famously, numerous antitrust bills were introduced into prior sessions of Congress. They did not have sufficient traction; they might be reintroduced. Almost all were specialized to specific conduct of big tech and would do nothing to change the general orientation of antitrust. S.225, introduced by Senator Klobuchar, did attempt to reset the antitrust compass, including for exclusionary conduct and mergers. It would, for example, change the standard for merger illegality from: “may be substantially to lessen competition” to: “create an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition.”

Contemplating the bill, we can understand the difficulty of changing antitrust law by standard-specific legislation. The Klobuchar standard is meant to be more aggressive than current law, but is it? It is not obviously so. The meaning of “appreciable risk” and “materially lessen” would be bound to face much contestation and litigation, up to the Supreme Court, which would give its imprimatur. There is nothing wrong with the existing statutory language to condemn anticompetitive mergers. The problem is the lens of interpretation.

There is a solution: US antitrust law was not always driven by libertarian premises. Indeed, in the aftermath of the Warren Court and ensuing course corrections, US antitrust was settling into an economically-sound progressive path. So here is a solution: Legislative repeal of the Supreme Court’s path-changing decisions that made a sharp turn to the right, just before the turn of the last century, and reinstating the jurisprudence at that time.

The set of cases that narrowed the concept of “anticompetitive that should be proscribed,” piled undue burdens on plaintiffs, and complicated proof would be repealed. These would include: Trinko, Brooke Group, Ohio v. American Express, and California Dental Association. US antitrust jurisprudence would explicitly return to the line of Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical and Aspen Skiing, and could also take guidance from Judge Wyzanski’s earlier opinion in United Shoe Manufacturing. The reconstituted jurisprudence would adopt Justice Breyer’s dissenting and concurring opinions in American Express and California Dental, and Justice Scalia’s opinion in Trinko would be replaced by the Second Circuit opinion that it reversed. These opinions together comprise a coherent narrative of market power and its abuse. On the other hand, the Scalia/Thomas line of jurisprudence disrupted the narrative, violating the Dworkian principle and concept of law’s evolution as a novel with each next chapter a harmonious fit. The reconstructed body of antitrust jurisprudence would reset the stage and present a reconstructed platform without interfering with the iterative fact/law process of evolution of antitrust law.

Proposals for specific rules, standards and burdens by scholars such as Jonathan Baker, Andy Gavel, Herbert Hovenkamp, Steven Salop, Fiona Scott-Morton, Eric Posner, and Carl Shapiro fit naturally into the aura of the reconstituted jurisprudence under the higher-level umbrella. Debate on the details would be in the courts, in decisions and opinions in actual cases on actual facts, not in the legislature.

3. FTC rule-making and guidance

The FTC could initiate focused rule-making; e.g. rules to govern Big Tech conduct that more or less follow the lists crafted by jurisdictions around the world. This project would be helpful if it could succeed – which is a challenge. But even if successful, the bespoke code of conduct would not change the right-leaning slant of the Sherman Act. The FTC has given general guidance in its policy statement on the Scope of Methods of Unfair Competition, 2022, but this statement is on the scope of the FTC Act, not the Sherman Act, and the narrative is 1960s law, not 1980s and ’90s law, and it has no limiting principle.

IV. What To Do About Wrongs Of Exploitation Of Small Players Without Power And Other Non-Market Values?

It is certainly worth considering reforms that will aid gig workers and others who are unfairly exploited. Salop and Melamed have made a proposal. The EU institutions have drafted a directive with a presumption that gig workers are employees. A US FTC Commissioner argues that gig workers are included in the labor exemption. Neo-Brandeisian philosophy embraces the flexibility of antitrust to address public interests.

I do not take on these issues in this essay. Traditional antitrust proper and its ideological capture is so serious that it needs a separate focus. Within the category of protecting consumers by antitrust enforcement (consumer welfare), Neo-Brandeisians agree with Progressives, as Jon Baker shows. Moreover, the lion’s share of the work of the Biden antitrust agencies is “consumer welfare” work. The critical coalition is not the proponents of the consumer welfare standard within the big tent versus Neo-Brandeisians, but Progressives including Neo-Brandeisians, who want to rip laissez-faire-ism from antitrust, and those who want to preserve it. Progressives who want to renew the vigor of antitrust but would limit antitrust to market factors, and Neo-Brandeisians, are divided by a common language. Putting “the consumer welfare standard” on a pedestal and making it a high principle for which you must fight obscures the real problem; the real fight for the soul of antitrust on pro-market soil.

Conclusion

The “consumer welfare standard” is an elastic phrase and is not a descriptive label. When used to mean the goal of antitrust, the consumer welfare standard is more accurately described as “helping make the market work.” For analyzing market conduct to determine whether it is anticompetitive and should be proscribed (standards for analysis), a goal does not and is not expected to give sufficient guidance. The caselaw embeds various standards and some rules and presumptions derived from them. They are alarmingly infused with the laissez faire perspective.

The important question is not whether we should keep the consumer welfare standard, but how to excise laissez faire from US antitrust. Given that the US Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter of antitrust caselaw and that the ideological balance of the Court is not likely to change in many of our lifetimes, change without legislation is not likely. In our common law system of iterative case-by-case adjudication rather than ex ante rules for antitrust, it is hard to change antitrust by legislating black letter law. Restoring the body of jurisprudence to the point in time before the Court took a sharp turn to the right is a better, cleaner route. This means legislative repeal of certain cases and reinstating opinions sympathetic with meaningful antitrust.

Whatever is the best road forward, we should not let devotion to “the consumer welfare standard” and the implication of like-mindedness in the big tent split the natural coalition of Neo-Brandeisians and Progressives (see Jon Baker) in fighting for a restored interpretation of: What is “anticompetitive”?

Eleanor Fox is Walter J. Derenberg Professor of Trade Regulation Emerita at New York University School of Law. Citations supporting this text can be found in Eleanor Fox, The Decline, Fall, and Renewal of U.S. Leadership in Antitrust Law and Policy, Competition Policy International (CPI) Antitrust Chronicle, April 2022, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4097141and CPI Talks with Eleanor M. Fox (Alice in Consumer welfareland), CPI Antitrust Chronicle, Nov. 2019 https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CPI-Talks-Fox.pdf

Articles represent the opinions of their writers, not necessarily those of the University of Chicago, the Booth School of Business, or its faculty.