Breaking up companies that antitrust regulators consider too dominant can be costly and might negatively impact innovation and consumer welfare. As economists and policymakers in the United States and Europe debate dismantling Big Tech companies, they should consider the lessons learned from the 1984 case of AT&T, write Monika Schnitzer and Martin Watzinger.

The alleged concentration of market power among Big Tech companies has sparked heated debate on both sides of the Atlantic. While some see it as a result of these companies’ innovative power, others worry about the impact on innovation and consumer choice. The US House Antitrust Committee has expressed concerns that these monopolies lead to “less innovation, fewer choices for consumers, and a weakened democracy.” Among other anti-competitive behaviors, the Big Tech companies allegedly use their dominance in one market as leverage in unrelated lines of business. Such exclusionary tactics can shield incumbents from competition, close off markets, and discourage potential entrants from innovating. To address these antitrust issues, the Committee recommends “structural separation and line of business restrictions.”

In theory, using structural remedies to prevent exclusionary practices can make sense, for example, when a vertically integrated company uses its control over an upstream “essential facility” (or “bottleneck” or “natural monopoly”) to exclude competitors in a downstream market. However, there is little empirical evidence on the advantages and disadvantages of breakups of dominant companies. This is unfortunate, since a breakup has potentially enormous costs and should be implemented only if the benefits are substantial and cannot be achieved in a less costly way. That is why competition law often focuses instead on regulatory measures and rules, like the Digital Markets Act in the E.U., which prohibits gatekeeper platforms from certain practices and requires them to follow certain behaviors.

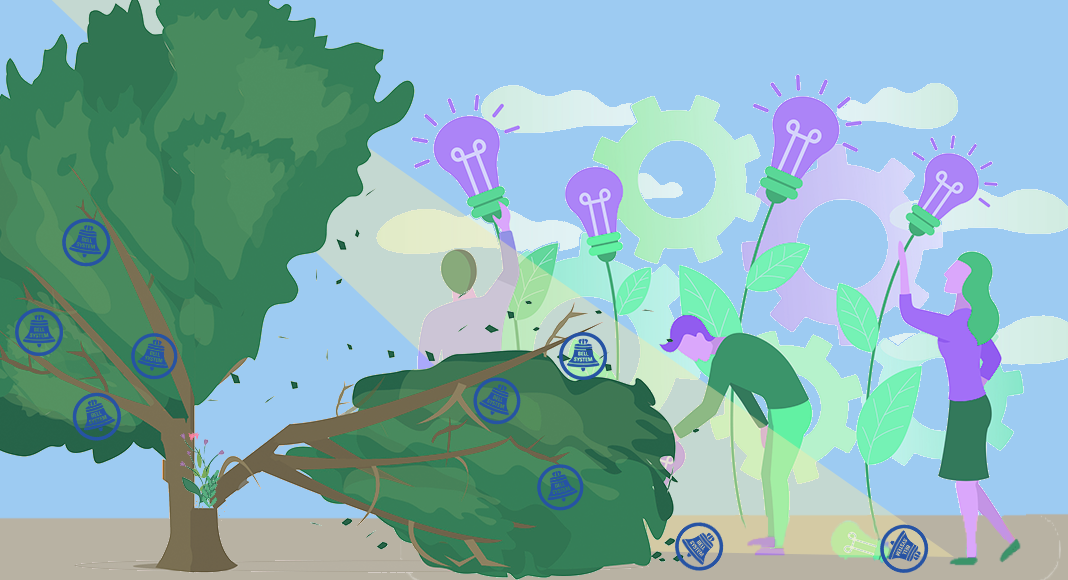

In recent research, we analyzed the impact of the 1984 breakup of the AT&T group, also known as Bell System, on innovation. The case is particularly informative because the breakup had the potential to undermine substantially U.S. innovation, as the Bell System was home to one of the most productive industrial laboratories of all time, the Bell Laboratories. The Bell Labs are credited with major inventions such as the cellular telephone technology, the transistor, the solar cell, the communication satellite, and the Unix operating system. Researchers at Bell Labs had received nine Nobel Prizes and four Turing Awards for its work.

Before the breakup, the Bell System was a vertically integrated telecommunications company with AT&T as the holding company. It had more than one million employees and controlled more than 85% of all local telephone services through its Bell Operating Companies. It had a market share of over 85% in long-distance services through its subsidiary AT&T Long Lines and an 82% market share in telephone equipment through its subsidiary Western Electric. As a network-based natural monopoly, AT&T was regulated at the state and the federal level. Yet, despite decades of regulation, competitors repeatedly complained that AT&T was using its market power in local telephone services to prevent market entry in the market for telephone equipment and the market for long-distance services.

To end the alleged exclusionary conduct of the Bell System, the US Department of Justice filed an antitrust case against AT&T in 1974, with the key accusation being vertical foreclosure. The Bell operating companies controlled the local telephone networks, which were an essential facility (or bottleneck) for reaching customers for companies producing telephone equipment or providing long-distance services. The DOJ accused Bell of abusing its control over the local telephone networks by effectively excluding competitors of Western Electric and AT&T Long Lines from reaching new customers. The case ended with a final ruling that imposed the structural separation of Bell’s Operating Companies (those providing local telephone networks) from the rest of the Bell System, effective January 1, 1984. Spinning off the essential facility was meant to facilitate market access and thus strengthen competition.

As a result of the breakup, Western Electric and AT&T Long Lines could no longer count on privileged access to Bell’s operating companies as customers. The newly independent Baby Bells were free to buy their equipment from outside the Bell System and indeed did so. From the competitors’ point of view, market entry was now within the realm of possibility, and they seized the opportunity.

As our empirical investigation shows, the breakup of the Bell System had a huge impact on US innovation in the telecommunications sector. One concern people had at the time of the breakup was that Bell’s patenting might suffer, so any potential positive effect of the breakup might come at the expense of valuable innovation. Indeed, as a consequence of the breakup, patenting by Bell Laboratories declined by about 100 patents per year, but the number of important patents – measured e.g. by the number of patents that belong to the Top 10% of the mostly cited patents in their technology subclass and filing year – did not.

And even if Bell‘s patenting declined somewhat in numbers after the breakup, this was more than compensated by the explosion of innovation by all other companies in telecommunications. Figure 1 compares the total number of patents of US inventors in technology groups in which Bell was active and which hence was most affected by the breakup (treated groups – solid red line) with the total number of patents in similar but unaffected groups (control groups – blue dashed line). To adjust for the higher overall levels of patenting in treated technology groups, we subtract the respective 1981 levels in both groups. Before 1982, the total number of patents in both groups follow a very similar trend. After the breakup was announced, the two lines begin to diverge. Patenting in the sector affected by the breakup grew by 19% more than patenting in the other but comparable sectors. Per year, that is 1000 additional patents, about 2.6% of all annual US patents by US inventors in the years after 1982. So in addition to having no impact on important patents from Bell Labs, the breakup spurred overall innovation in the sector by nearly 20%.

The breakup increased not only the rate of innovation but also its diversity. In technology fields affected by the breakup, we found an over-proportional increase in the number of different technological approaches explored. Moreover, based on textual analysis of patents and patent citations, we found that the direction of innovation changed away from Bell’s approaches to new ideas.

Both the overall increase in patent applications and the change in direction indicate that the period before the breakup was one of missing innovations. This observation is consistent with the well-known replacement effect: an incumbent is reluctant to invent products that could replace or cannibalize his existing business model.

Anecdotal evidence about Bell’s missing inventions supports this interpretation. As a monopolist, Bell had little incentive to increase product diversity: Only seven decades after Bell invented the telephone did AT&T offer its phones in a color other than black. Company documents also indicate that the Bell management deliberately withheld the answering machine from the public, which was developed at the Bell Laboratories in 1934, out of concern that introducing answering machines would reduce demand for their telephone services. It is also striking that Finnish consumers had access to cell phones two years earlier than US consumers, even though many of the underlying technologies were developed by Bell. The cell phone was introduced to the US market only after the breakup.

Can the Bell breakup serve as a model for today’s antitrust cases? It was meant to isolate the essential facility of the local telephone services from the rest of the Bell System. This was an attractive structural remedy to ensure that Bell could no longer use its essential facility – the local telephone lines – to prevent competitors from successfully entering the market for telecommunications equipment or long-distance services. The question today is whether the Big Tech companies control essential facilities that they can use to exclude competitors in related markets. If competitors stand ready to enter these markets once exclusionary behavior is ended – as was the case after Bell’s breakup – our analysis would suggest that US innovation could benefit from the implementation of structural remedies.