Using the 2019 BB&T-SunTrust merger as a case study, Laura Beltrán argues that contemporary antitrust policy, based on the Consumer Welfare Standard, fails to consider how mergers disproportionately negatively affect women and people of color.

Gender and race discrimination regulations, such as those seeking to rectify the pay gap between men and women, often rely on legal and policy arguments rather than economic theories. However, gender and racial disparities in the workplace can also be seen as an abuse of labor market monopsony and should be studied under antitrust law. Particularly, mergers can have a disproportionate impact on the employment of women and people of color, a troubling pattern given the increased frequency with which mergers have occurred since the adoption of the Consumer Welfare Standard as the dominant legal theory behind antitrust enforcement in the 1980s.

Mergers, by definition, result in the consolidation of two companies into one. When this occurs, it is common for there to be overlap in certain roles, such as administration, production, and management, resulting in layoffs to reduce costs and redundancies. These job cuts often target lower-level positions, since they tend to be less specialized in nature and have the largest employee shares. Historically, women and people of color have been overrepresented in lower-level positions and underrepresented in the highest-wage workforce.

According to the Current Population Survey (CPS), women comprise 58% of the low-wage workforce and 69% of the lowest-wage workforce, referring to those occupations that typically pay less than $10 per hour. Black and Latinx workers are similarly overrepresented in the low- and lowest-wage workforce. Collectively, they account for more than 41% of the low-wage workforce and 36% of the lowest-wage workforce, despite comprising only 27% of the total workforce. Contemporary antitrust policy’s inability to address how mergers target women and minority labor highlights the Consumer Welfare Standard’s shortcomings and underlines the need for a more sophisticated antitrust criteria.

The merger of BB&T and SunTrust in 2019 provides an apt case study of how mergers disproportionately harm women and people of color in the workforce. On December 19 of that year, the two companies merged to form Truist Bank, now the sixth biggest bank in the US with assets over $400 billion.

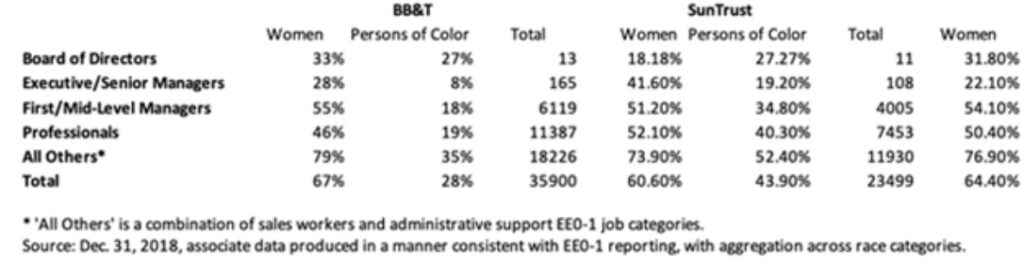

The Corporate Social Responsibility Reports filed by each company before and after the mergers reveal company-specific demographic information and how the merger disproportionately impacted women and people of color. Figure 1 highlights the gender and minority worker distribution pre- and post-merger for the fiscal years 2018 and 2019. In 2018, BB&T had 35,900 workers, while SunTrust had 23,499, for a total of 59,399 employees. After the merger, Truist had a total of 58,767 employees. The workforce was hence reduced by 632 employees.

In 2018, 67% of BB&T employees were women, as were 60.6% of SunTrust employees. Thus, 65.1% of the combined workforce of the two companies pre-merger were women. After the merger, the percentage of women employees fell to 64.4%. The total number of women employees decreased from 38,669 before the merger to 37,846 after the merger, for a reduction of 823. Given that the companies cut a net 632 employees after their merger, this means that women accounted for all of the workforce reduction and were in some cases replaced by newly hired men.

More staggeringly, the composition of executive and senior managers before the merger was 28% women for BB&T and 41.6% women for SunTrust. This proportion fell to 22.1% post-merger. Similarly, there were 9% fewer people of color sitting on the Board of Directors post-merger. The total number of persons of color working as sales workers and administrative support also fell by 427.

Figure 1. Differences Between Pre and Post-Merger Gender and Race Distribution

As the economic theory on mergers predicts, the biggest layoffs after the BB&T-SunTrust merger occurred at lower-level positions, namely sales workers, administrative support, and professionals. Only three individuals were laid off from the Board of Directors and executive and senior manager positions post-merger, while 518 individuals from the professionals, sales, and administrative support categories were laid off. A reminder that 427, or 82%, of these individuals were people of color.

Over the last few decades, US state and federal labor policy has sought to protect women and people of color in the workforce from discrimination. Antitrust policy under the Consumer Welfare Standard has failed to keep up. By truncating “valid” antitrust inquiries to “purely economic” consumer consequences, antitrust policy erases the considerations of workers, particularly women and people of color. In practice, contemporary antitrust policy equates the losses of these marginalized groups to the gains of white executives and consumers under the narrow parameters of increases in efficiency and price reductions (whose realizations are highly debatable in many situations).

Concentration expressed in rising mergers and acquisitions might worsen diversity across firms and hinder women and people of color from climbing the professional ladder. In such situations, an emphasis on consumer welfare tips the balance in favor of the (white male) majority at the expense of protected minorities. Preserving competition not only generally improves consumer welfare but also helps to address racial and gender labor disparities.

A more encompassing antitrust standard should remedy dominating corporations’ noxious influence on labor and address issues of diversity and labor mobility for women and people of color. Direct action via antitrust enforcement is one possibility, but due process and the rule of law may impede such attempts in the short term. Those who argue for a larger agenda are sometimes referred to as “populists” or “hipsters,” and their efforts are often shut down. However, these “populists” and “hipsters” are only rejecting unjustifiable restrictions imposed by an antiquated economic approach to welfare, or at least an untenable interpretation of that approach. In a political environment where women and persons of color are fighting for their rights, why has antitrust decided to turn a blind eye to favor the white male majority?