The bill, which is the Senate is expected to vote on soon, would improve competition, increase innovation, benefit consumers, and provide the US with a much-needed role in the regulation of digital platforms.

Editor’s note: The following is based on a letter sent to Senators in support of the digital platform regulation bill that is currently under consideration in the Senate.

After careful thought, including consideration of a one-paragraph letter circulated to Senators from a group of antitrust scholars opposing it, we write to share our conclusion that the American Innovation and Choice Online Act (“American Innovation”) would improve competition, increase innovation, and benefit consumers in digital markets, and therefore should become law in the US.

Large digital platforms have obtained market power over the last fifteen years due, in part, to insufficiently effective antitrust enforcement and to underlying economic conditions that are conducive to concentration and significant barriers to entry. These economic factors include network effects, economies of scale and scope, the role of data, and consumer behavior.

Today, these platforms have become entrenched while at the same time they serve as the gatekeepers of economic, social, and political activity on the internet. Evidence is mounting that their control of these critical gateways is stifling competition and innovation to the detriment of consumers. American Innovation’s approach is targeted rather than scattershot, in that its prohibitions apply only to platforms deemed “critical trading partners”—meaning, they have the power to deprive business users of access to customers or access to inputs necessary for those users to run their businesses. The result is that American Innovation’s restrictions apply to the platforms whose market positions confer undue gatekeeping power, and no others. It is an appropriate expression of democracy for Congress to enact pro-competitive statutes to maintain the vibrancy of the online economy and allow for continued innovation that benefits non-platform businesses as well as end users.

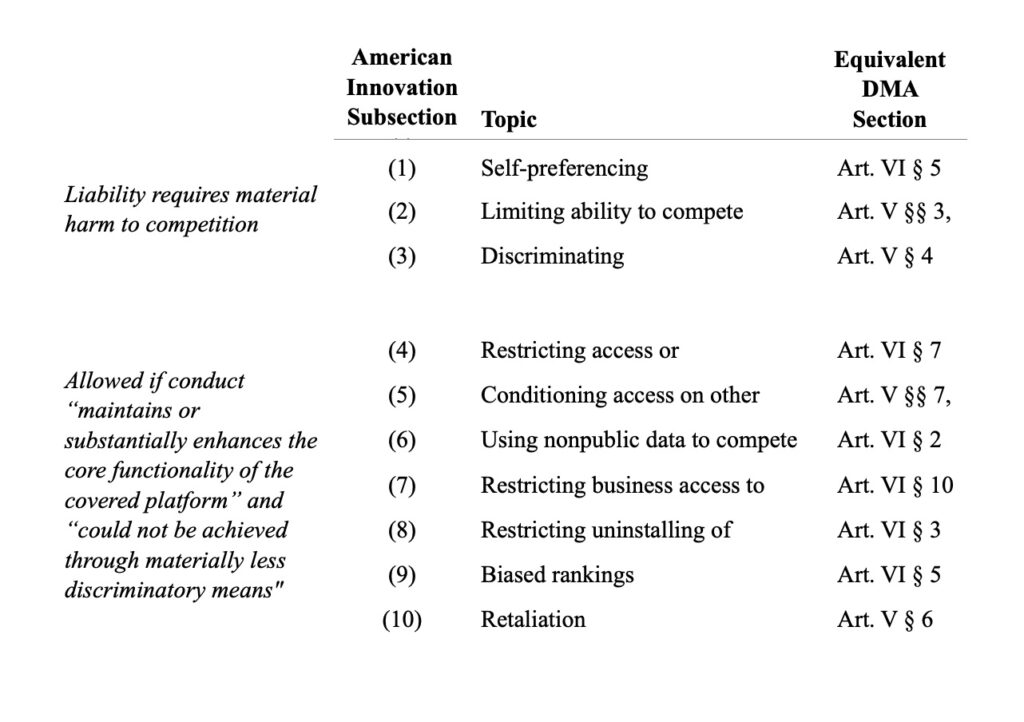

American Innovation’s first three general provisions prohibit classes of conduct (discrimination, self-preferencing, and limiting ability to compete) by large platforms that “would materially harm competition.” This terminology is a change from the current requirement that plaintiffs challenging anticompetitive conduct must show “substantial”harm to competition. Most of the academic criticism of this bill expresses a dislike of this new and different language, and protests that it is ambiguous.

But different language is a feature, not a bug, of this bill. The decline of antitrust enforcement in the US is well known, pervasive, and has left our jurisprudence unable to protect and maintain competitive markets. There are many sources detailing this trend; an excellent summary can be found in a prior letter to Congress that was signed by several of the same people who object to American Innovation. These findings have overwhelming empirical support in the economics literature, which is only growing over time. For this reason, it is necessary to strengthen competition laws. This bill will strengthen competition enforcement only in the narrow context of digital platforms, but that is an important step.

To clarify for courts and policymakers that Congress wants something different (and stronger), new terminology is required. The bill’s language would open up a new space—and surpass the Sherman Act, which has not effectively policed digital platforms over the last twenty years. The law mandates that the FTC and DOJ, the two expert agencies in the area of competition, together create guidelines to help courts interpret the law. Any uncertainty about the meaning of words like “competition” will be resolved in those guidelines, and over time with the development of caselaw. This is the same method by which other statutes acquire definitive meaning and is consistent with our common-law tradition.

A second concern that is rarely stated explicitly, but clearly forms an undercurrent of discomfort on the part of critics, is that a single small competitor who cannot survive in the marketplace might be able to sue to make big platforms accommodate it, thereby harming the quality of products and services available to consumers. First, only the federal agencies and state attorneys general would have standing to bring cases under this law, so frivolous private litigation will not occur. And second, the outcome that critics fear would require the agencies to contend, and courts to accept, that somehow, by hosting robust, open, and non-discriminatory competition in which some competitors do not succeed, the platform is “materially harming competition.” This is, of course, not plausible, which greatly reduces the likelihood a court would so hold. Moreover, current judges, attorneys, and experts have been trained in the current language of competition and tend to think about competition questions through that lens—which is remarkably weak. Forty years of constantly receding antitrust enforcement due to the influence of the Chicago School and its cramped view of what counts as injury to competition laid the groundwork for a string of more recent cases—well known to the antitrust bar simply by reference to single-word party names (AmEx, Qualcomm, for example) in which, despite evidence to the contrary, courts have struggled to find harm to competition.

“different language is a feature, not a bug, of this bill. The decline of antitrust enforcement in the US is well known, pervasive, and has left our jurisprudence unable to protect and maintain competitive markets.”

When courts apply the FTC and DOJ guidelines to the new law, many of the same judges who were called upon to render decisions under the old antitrust regime will be called upon to render decisions under the new one. They will be the same people with the same worldview. The goal of the new language, which will be made more precise through guidelines, is to move courts in a more enforcement-oriented direction. Shifting a whole legal community and its understandings is hard. It is therefore unduly optimistic to imagine outcomes under the new law would veer drastically away from past understandings of core concepts like harm to competition. In light of this, claims of legal “chaos” created by a slew of radical or unforeseen decisions are unjustified.

The second part of American Innovation lists specific prohibited conduct (restricting interoperability, restricting business access to data, conditioning access on other services, etc.). Critics reading this list may imagine their favorite products and services will be banned. But American Innovation provides a powerful defense that forecloses any thoughtful concern of this sort: conduct otherwise banned under the bill is permitted if it would “maintain or substantially enhance the core functionality of the covered platform.” A well-run platform presumably makes almost every decision with the goal of maintaining or enhancing its functionality, and therefore good faith business decisions will be protected.

Indeed, given that defense, one might wonder how the bill will effectively restrain the conduct it aims to prohibit. The functionality defense is subject to a requirement that “the conduct could not be achieved through materially less discriminatory means.” In other words, the improved functionality (and therefore the innovation the bill is trying to protect and increase) trumps any violation of the behaviors on the list—unless there is another way to achieve the same innovation that is materially less discriminatory to competitors. Critically, and as is typical with elements of an affirmative defense, it is up to the platform itself to convince the court that its conduct is not pretextual and meets the other requirements of the defense. In other words, platforms will not be permitted to cloak anticompetitive conduct with a claim of innovation if that innovation could be implemented in a way that does not harm competition. Because the platforms have the most information about alternative means by which they could have implemented their innovations, they should have no problem defending legitimately pro-competitive decisions.

Scholars of antitrust enforcement in the US understand that the current level of competition enforcement against corporations is weak and needs to be increased. American Innovation’s liability standards purposefully differ from prior standards in that they are easier for plaintiffs to meet than are the standards in use under other antitrust statutes today. The revised standards, however, continue to call upon familiar concepts. Anything unfamiliar almost certainly will be the subject of joint FTC-DOJ guidelines that, according to the terms of the bill, must be issued within 270 days of the bill’s enactment. Those guidelines will include enforcement policies relevant to conduct that may materially harm competition and agency interpretation of the affirmative defenses. The fact that guidelines must issue promptly directly counters complaints about purported “uncertainty,” yet none of the written critiques of which we are aware engages with prospect of guidelines at all, let alone explains why we should expect the guidelines to be unhelpful. The use of terms and concepts that are familiar, in combination with guidelines addressing anything new, should make the changes feel incremental rather than radical or abrupt.

In this sense, the bill is a very nice middle ground. Critics on both the right and left extremes of antitrust scholarship can find things about the bill to criticize, which, in itself, indicates it occupies space in the center. Specifically, some conservative antitrust skeptics claim the bill is divorced entirely from the traditional requirement of competitive harm. That view is inaccurate, as we explained above. Some critics on the left prefer “bright-line rules.” They contend that establishing liability should not require analysis of market facts, product characteristics, and consumer behavior, which can demonstrate whether and how competition has been harmed. But we think the bill’s requirement of analysis is a good feature; it helps courts and agencies ensure that the law punishes harmful conduct only.

An important reason to support this bill that has not been highlighted in the public discussion is the ability of the expert agencies to incorporate additional protections into the guidelines. In this sense, the bill is not a pure antitrust law but also safeguards other benefits to consumers and businesses. For example, effective competition requires consumer protection so that consumers are aware of the quality of the product or service they are choosing and are not being exploited or defrauded; the intersection between this issue and competition can be addressed in guidelines. Another example is the openness created by access requirements that increases competition but may create security risks, and guidelines can play a role in balancing these issues.

The European Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA) very shortly will become law in the European Union. American Innovation gives the US a role in the regulation of these important global platforms, many of which were founded here. Without American Innovation, the role of protecting competition and innovation in the digital sector outside China will be left primarily to the European Union, abrogating US leadership in this sector.

Further, American Innovation is a practical option because it covers much of the same ground as the provisions in the DMA. (See Table 1, infra.). Because the large platforms will be preparing to comply with the DMA and DSA in 2023, and will be coming into full compliance in 2024, their European operations can naturally comply with American Innovation. Consumer gains from American Innovation will come at minimal additional cost to platforms—other than the loss of undeserved monopoly profit—because the technologies will already have been created and deployed in Europe. Moreover, the existence of the European laws profoundly alters the costs and strategies of the covered platforms. Without American Innovation, large platforms might prefer to run a business model in the US that discriminates against, or blocks entry of, new competitors and complementors—even though they must maintain a competitive platform in Europe. Such a situation could cause the center of gravity for innovation and entrepreneurship to shift from the US to Europe, where the DMA would offer greater protections to start ups and app developers, and even makers and artisans, against exclusionary conduct by the gatekeeper platforms.

Finally, we address the criticism that American Innovation will inadvertently make content moderation difficult because some of prohibitions purportedly could be read to include in their sweep some varieties of content moderation. The mere possibility a litigant might attempt to pigeonhole incidents of “censorship” into a definition plainly not intended to cover such conduct, or that an activist judge might condone such misuse, is not a reason to oppose the American Innovation. If laws will be intentionally misconstrued, it may not be worthwhile enacting any laws at all, as mischief of the sort critics envision could be made using any law, new or old. Rather, offering comments on a bill we believe will confer widespread benefits on the American people presupposes that courts do something other than simply exercise raw power. Courts decide, and they will continue to decide on, the law.

We present these reasons to explain why we disagree with critics, including the authors of a letter recently addressed to members of the Senate that says: “this bill is not well-designed to accomplish this goal. As presently drafted, it would very likely reduce innovation, [sic] and harm consumers.” (The letter, from “Professors of law, economics, and business” to “Senators,” circulated June 20, 2020, is on file with these authors.) That letter is not convincing because it contains no explanation or justification of the signatories’ views. After considering the recent experience of US antitrust enforcement, present problems in the digital economy, and action in Europe, we find their arguments are inapt or have little persuasive power as we have explained above. Accordingly, we express our strong support for American Innovation.

Sincerely yours,

Fiona M. Scott Morton, Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics at the Yale School of Management

Steven C. Salop, Professor Emeritus at the Georgetown University Law Center

David C. Dinielli, Senior Policy Counsel, Tobin Center for Economic Policy at Yale University and Visiting Clinical Lecturer in Law at the Yale Law School

Additional reading:

Letter of Phil Weiser, Attorney General for the State of Colorado, to Senators Durbin, et al. and to Congressman Jordan (June 1, 2022), in support of American Innovation.

Disclosures: The authors have consulted for companies covered under the bill and for government agencies both here and abroad on tech issues.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.