Three months ago, Russia invaded Ukraine. With the continued warfare, the world—only just recovering from the devastating effects of the Covid-19 pandemic—has been plunged into severe political, social, and economic disruptions. In Nigeria, those disruptions could soon mean that most adults will struggle to access necessities.

In a recent event at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State facilitated a discussion with students, faculty, and journalists to unpack how the war in Ukraine affects people politically and economically across the world.

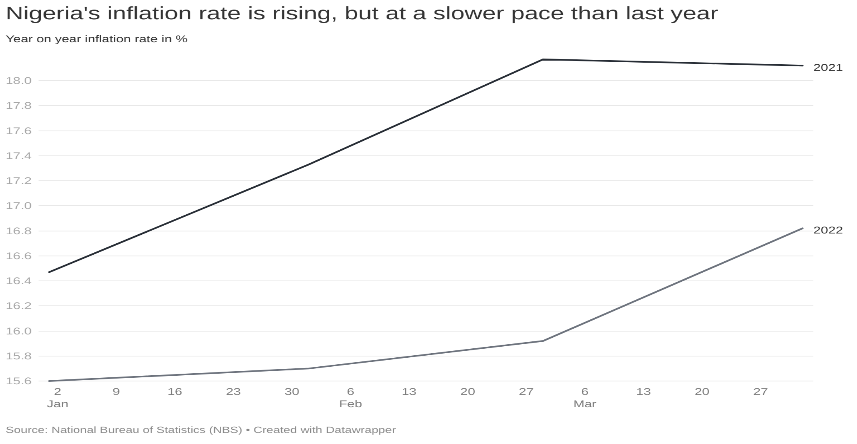

For Nigeria, which imports more than 50% of its wheat requirement from Russia and other black sea countries, the prolonged war is causing supply disruptions and contributing to high food prices. The consumer price index which measures the overall inflation rate in Nigeria increased to 16.8% in April from 15.6% in January 2022. Although this rising price is exacerbated by the war, the increase is much slower when compared with the effect Covid-19 had on the country one year ago.

Such high prices are particularly noticeable in food items like bread and is worrying because 6 out of 10 Nigerians struggled to access or afford food even before the war in Ukraine. Poor social safety net measures in the country means many Nigerians resort to borrowing money just to eat. For instance, 41% of pre-pandemic personal loans were taken out to buy food, a rate that jumped to 51% between March 2020 and August 2020.

Essentially, acute hunger could rise globally (not just in Nigeria) by as much as 47 million people if the conflict in Ukraine continues unabated beyond April. The World Food Program puts this rise in the number of people experiencing food shortages at a “staggering 17% jump, with the steepest rises in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Oil and gas boycotts contribute to supply disruptions

However, the higher food prices and worsened shortages are not the only implications of the invasion: increasing oil and gas prices have sent transportation and manufacturing costs higher and also increased the price of most consumer goods.

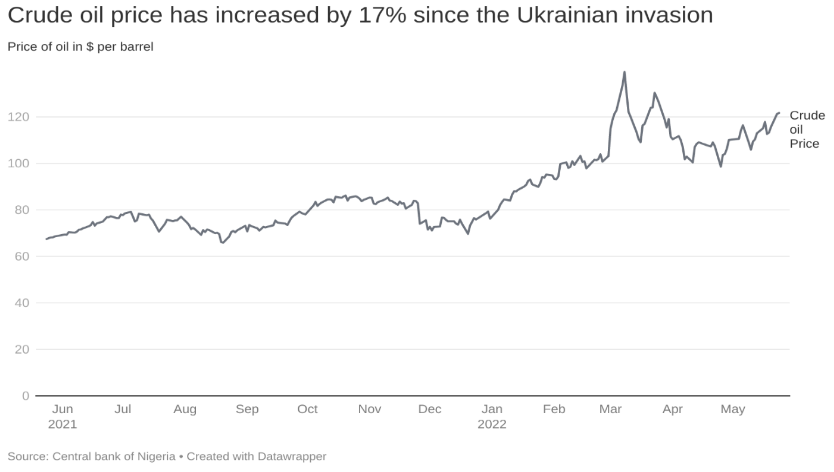

For some background, the surge in energy prices started before Covid. This Reuters report shows that energy producers cut back on investment and less profitable projects pre-pandemic. Then oil producers slashed output further during the pandemic when the need for petroleum products fell. With the world reopening in 2021, demand for oil began to grow, much faster than the diminished supply, thereby raising oil prices. Now, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the latest catalyst to push crude prices even higher.

Europe is boycotting Russia’s oil and gas, tightening an already tight energy market. Russia is the third-largest oil supplier behind the US and Saudi Arabia. Russian gas is extremely important to Europe: in 2021, Russia supplied a third of the region’s oil. The price of Brent Crude (a common variant of oil) by 17% since the beginning of the invasion.

The International Energy Association (IEA) believes this disruption will reduce global supply by 1.5 million barrels daily and eventually 3 million barrels daily in May. The reduction would be equivalent to a third of what the US alone uses in powering their vehicles each day.

On the surface, higher prices and higher demand should mean more income and robust foreign reserves for Nigeria, which is also an oil producing country. However, because Nigeria lacks refining capabilities, it imports refined petroleum. So most of the gains the country should be earning from the supply disruption get lost in the exchange of crude oil for refined oil, food, and other imports.

Speaking of imports, one major resource Nigeria spends its foreign reserves on is steel. In 2019, Nigeria spent $2.2 billion importing metals from across the world. Nearly 60% of trade between Nigeria and the warring countries (Russia and Ukraine) in the same year were metals.

Incidentally, Russia has a deal with Nigeria to complete Ajaokuta Steel—the country’s steel mill. But, the ongoing war makes the fate of the project uncertain.

As Nigeria grapples with a potential further delay in reviving the steel mill, which is vital to the manufacturing and construction industries, struggles with foreign earnings, soaring inflation rates, food shortages and other implications of this prolonged war, there is still room to be a little bit optimistic.

Nigeria has the 9th largest natural gas reserves in the world and over 60% of its population work in the agriculture sector—a huge opportunity in times of crisis such as this. For instance, there is a pipeline project Nigeria is undertaking with Morocco to get gas to Northern Africa and Europe.

Thankfully, the country is ramping up investment in areas like gas supply and domestic food production. With effective application of these investments and further international collaborations, tangible results that reduce the challenges from the war, might take less time to materialize.

Surely, the war ending sooner rather than later will bring quicker respite to these challenges. But despite several peacekeeping efforts, the warring countries persist, and so Nigerians can only hope they will bring the war to a speedy end.