Chinese reformers after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 agreed that it was necessary for China to move towards marketization, but struggled over how to go about doing that. In an excerpt from her book How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate, Isabella M. Weber explains how China managed to achieve rapid growth without fully adopting the shock therapy-style reforms that typified market liberalization in Eastern and Central European countries.

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

Contemporary China is deeply integrated into global capitalism. Yet, China’s dazzling growth has not led to a full-fledged institutional convergence with neoliberalism. This defies the post–Cold War triumphalism that predicted the “unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism” around the globe. The age of revolution ended in 1989. But this did not result in the anticipated universalization of the “Western” economic model. It turns out that gradual marketization facilitated China’s economic ascent without leading to wholesale assimilation. The tension between China’s rise and this partial assimilation defines our present moment, and it found its origins in China’s approach to market reforms. My book How China Escaped Shock Therapy uncovers the intellectual foundations of China’s marketization and thus helps us understand China’s distinct reform path that has given rise to a new kind of economic system.

The literature on China’s reforms is large and diverse. The economic policies that China has adopted in its transformation from state socialism are well known and researched. Vastly overlooked, however, is the fact that China’s gradual and state-guided marketization was anything but a foregone conclusion or a “natural” choice predetermined by Chinese exceptionalism. In the first decade of “reform and opening up” under Deng Xiaoping (1978–1988), China’s mode of marketization was carved out in a fierce debate. Economists arguing in favor of a shock therapy–style liberalization battled over the question of China’s future with those who promoted gradual marketization beginning at the margins of the economic system. Twice, China had everything in place for a “big bang” in price reform. Twice, it ultimately abstained from implementing it.

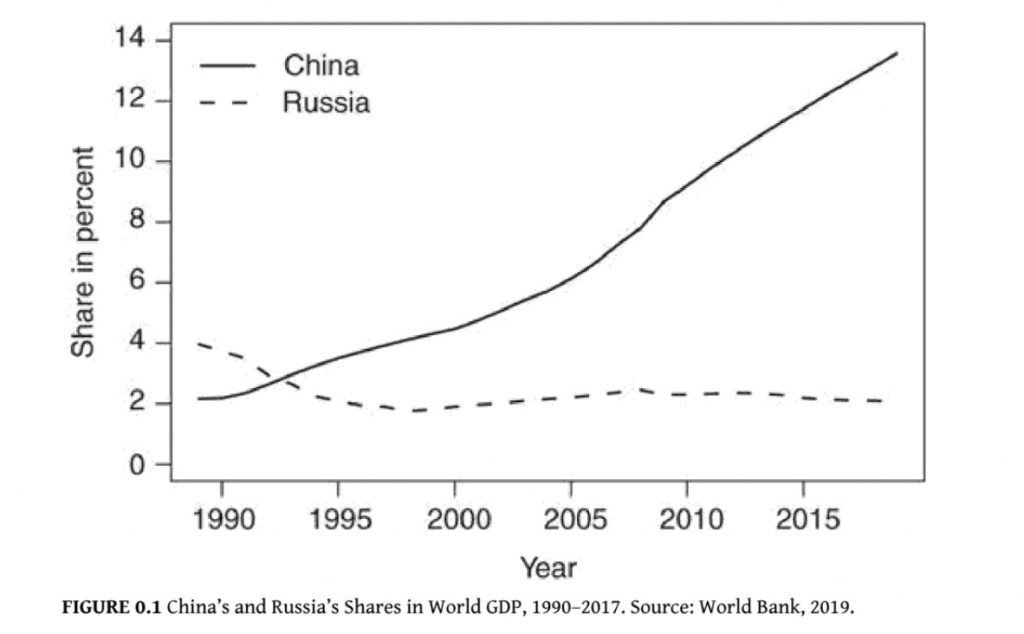

What was at stake in China’s market reform debate is illustrated by the contrast between China’s rise and Russia’s economic collapse. Shock therapy—the quintessentially neoliberal policy prescript—had been applied in Russia, the other former giant of state socialism. Nobel Memorial Prize laureate Joseph Stiglitz attests “a causal link between Russia’s policies and its poor performance.” Russia’s and China’s positions in the world economy have been reversed since they implemented different modes of marketization. Russia’s share of world GDP almost halved, from 3.7 percent in 1990 to about 2 percent in 2017, while China’s share increased close to sixfold, from a mere 2.2 percent to about one-eighth of global output (see Figure 0.1). We have to remember, at the beginning of reform and opening China was still a very poor country. In 1980, Chinese GDP per capita was less than that of Haiti or Sudan. While China became the proverbial workshop of world capitalism, Russia underwent dramatic deindustrialization.The average real income of 99 percent of people in Russia was lower in 2015 than it had been in 1991, whereas in China, despite rapidly rising inequality, the figure more than quadrupled in the same period, surpassing Russia’s in 2013. As a result of shock therapy, Russia experienced a rise in mortality beyond that of any previous peacetime experiences of an industrialized country.

Given China’s low level of development compared with Russia’s at the dawn of reform, shock therapy would likely have caused human suffering on an even more extraordinary scale. It would have undermined, if not destroyed, the foundation for China’s economic rise. It is hard to imagine what global capitalism would look like today if China had gone down Russia’s path.

Despite its momentous consequences, the key role played by economic debate in China’s market reforms is largely ignored. The famous Harvard development economist Dani Rodrik represents the economics profession more broadly when he answers his own question of whether “anyone [can] name the (Western) economists or the piece of research that played an instrumental role in China’s reforms” by claiming that “economic research, at least as con- ventionally understood” did not play “a significant role.”

In How China Escaped Shock Therapy, I take us back to the 1980s and ask on what intellec- tual grounds China escaped shock therapy. Revisiting China’s market reform debate uncovers the economics of China’s rise and the origins of China’s state-market relations.

China’s deviation from the neoliberal ideal primarily lies not in the size of the Chinese state but in the nature of its economic governance. The neoliberal state is neither small nor weak, but strong. Its purpose is to fortify the market. In the most basic terms, this means the protection of free prices as the core economic mechanism. In contrast, the Chinese state uses the market as a tool in the pursuit of its larger development goals. As such, it preserves a degree of economic sovereignty that buffers China’s economy against the global market—as the 1997 Asian and the 2008 global financial crises forcefully demonstrated. Abolishing this form of “economic insulation” has been a long-standing goal for neoliberals, and our present. China’s escape from shock therapy meant that the state maintained the capacity to insulate the economy’s commanding heights—the sectors most essential to economic stability and growth—as it integrated into global capitalism.

“The gradualist reform that set China on a path of catching up, reindustrializing, and reintegrating into global capitalism also implied that the institutional convergence between China and the neoliberal variety of capitalism remained incomplete.”

The Logic of Shock Therapy

Shock therapy was at the heart of the “Washington consensus doctrine of transition,” propagated by the Bretton Woods institutions in developing countries, Eastern and Central Europe, and Russia. On the surface, it was a comprehensive package of policies to be implemented in a single stroke to shock the planned economies into market economies at once. The package consisted of liberalization of all prices in one big bang, privatization, trade liberalization, and stabilization, in the form of tight monetary and fiscal policies. A closer analysis reveals that the part of this package that can be implemented in one stroke boils down to a combination of price liberalization complemented with strict austerity. Even the most hardcore shock therapists acknowledged that privatization takes time. A big bang in price liberalization was thought of as a condition for both privatization and trade liberalization and constitutes the “shock” in shock therapy.

What was presented as a comprehensive reform package turned out to be a policy that is extremely biased toward only one element of a market economy: the market determination of prices. This one-sidedness was not a mere result of feasibility, however. The deeper reason for the bias toward price liberalization lies in the neoclassical concept of the market as a price mechanism that abstracts from institutional realities. In the outlook of neoliberals more broadly, the market is the only way to rationally organize the economy, and its functioning depends on free prices.

The nature and structures of the prevailing institutions that would compose the new market economy did not receive much attention from shock therapists. The recommended package did not “create” a market economy. Instead, it was hoped that destruction of the command economy would automatically give rise to a market economy. It is a recipe for destruction, not construction. Once the planned economy had been “shocked to death,” the “invisible hand” was expected to operate and, in a somewhat miraculous way, allow an effective market economy to emerge.

This is a perversion of Adam Smith’s famous metaphor. Smith, a close observer of the Industrial Revolution unfolding in front of his eyes, saw the human “propensity to truck, barter and exchange one thing for another” as the “principle which gives occasion to the division of labour,” but he immediately cautioned that this principle was “limited by the extent of the market.” The market, according to Smith, unfolded slowly as the institutions facilitating market exchange were being built up. In this course, the invisible hand could come into play only gradually and, with it, the price mechanism. In contrast, the logic of shock therapy makes us believe that a country can “jump to the market economy.”

The destruction prescribed by shock therapy does not stop at the economic system. A further condition must be fulfilled: as Lipton and Sachs (1990, 87) put it, “(t)he collapse of communist one-party rule was the sine qua non for an effective transition to a market economy.” It did, in fact, require the collapse of the Soviet state and the communist one-party rule in December 1991, before a big bang could be implemented. “The collapse of communist one-party rule” turned out to be “the sine qua non” for a big bang, but the big bang failed to achieve “an effective transition to a market economy.” Instead of the predicted one-time increase in the price level, Russia entered a prolonged period of very high inflation, combined with a drop in output followed by low growth rates. Almost all of the post-socialist countries that applied some version of shock therapy experienced a deep and prolonged recession.

Instead of destroying the existing price and planning system in the hope that a market economy would somehow emerge “from the ruins,” China pursued an experimentalist approach that used the given institutional realities to construct a new economic system. The state gradually re-created markets on the margins of the old system. As I argue in the book, China’s reforms were gradual—not merely in the matter of pace but also in moving from the margins of the old industrial system toward its core. Unleashing a dynamic of growth and reindustrialization, gradual marketization eventually transformed the whole political economy while the state kept control over the commanding heights. The most prominent manifestation of China’s reform approach is the dual-track price system, which is the opposite of shock therapy. Instead of liberalizing all prices in one big bang, the state initially continued to plan the industrial core of the economy and set the prices of essential goods while the prices of surplus output and nonessential goods were successively liberalized. As a result, prices were gradually determined by the market.

By the end of the 1970s, China had largely given up on the revolutionary ambitions of late Maoism. The defining question of the 1980s was not whether to reform— as the commonly invoked binary of conservatives versus reformers stresses. The question was how to reform: by destroying the old system or by growing the new system from the old.

To use a metaphor, if shock therapy proposed to tear down the whole house and build a new one from scratch, the Chinese reform proceeded like the game of Jenga: only those blocks were removed that could be flexibly rearranged without endangering the stability of the building as a whole, while the gaps left behind were filled with the market. Through this process, the building was fundamentally changed. As everyone who has played Jenga knows, certain blocks may not be removed lest the tower collapses. But as the gaps were filled and not left empty, the tower did not reach the breaking point as it must happen eventually when playing the game of Jenga.

China almost implemented the destructive move of shock therapy by prematurely scrapping essential price controls in the critical first reform decade (1978–1988). But it ultimately abstained. The gradualist reform that set China on a path of catching up, reindustrializing, and reintegrating into global capitalism also implied that the institutional convergence between China and the neoliberal variety of capitalism remained incomplete. Like in the game of Jenga, the new tower was shaped by the structures of the old. As such, an escape from shock therapy was critical for both China’s economic rise and its partial institutional assimilation.

Excerpted from How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate, Isabella M. Weber (Routledge 2021). © 2021 Isabella M. Weber.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.