According to a theory that is gaining support among academics and practitioners, we should expect index fund managers to undertake the role of “climate stewards” and push companies into reducing their carbon footprint. In a new paper, Roberto Tallarita shows the limits of this theory and suggests that policymakers should not rely on index fund stewardship as a substitute for traditional climate regulation.

Index funds own a large fraction of the US stock market. According to some estimates, the so-called “Big Three”—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street, the largest index fund managers in the world—are together the largest shareholders in 40 percent of the publicly listed companies in the United States and in 88 percent of the companies in the S&P 500. By 2039, they are projected to vote 41 percent of the shares in S&P 500 companies.

Many experts are worried about such a massive concentration of ownership and voting power. Others, by contrast, believe that index fund managers will use their growing influence to persuade companies to reduce their carbon emissions and therefore mitigate the risk of climate change for society.

This optimistic prediction is based on a simple and suggestive theory, which I will call “portfolio primacy theory.” Climate change is a quintessential negative externality: individual companies have no incentives to reduce their carbon emissions because they would bear the entire cost of the reduction while most of the benefits would be reaped by someone else. Index funds, by contrast, “hold the entire economy,” and therefore, the argument goes, internalize the costs and benefits of carbon emissions and carbon mitigation. By maximizing the value of their entire portfolio (portfolio primacy) rather than the value of each individual company (shareholder primacy), index funds should be expected to pressure their portfolio companies to mitigate their impact on climate change, even if such mitigation comes at the expense of some individual companies.

But to what extent can we trust index fund managers to become effective climate stewards and mitigate climate risk for society? In my new paper “The Limits of Portfolio Primacy,” I argue that the optimism surrounding this view is grossly overstated.

Stock Prices Do Not Necessarily Reflect Climate Risk

To begin with, it is far from clear whether stock prices accurately reflect climate risk. The emerging literature on climate finance has found mixed evidence on this issue. Furthermore, many investment managers believe that stock prices underestimate climate risk.

If stock prices do not fully incorporate climate risk, they will not fully reward investors for climate mitigation. Why would an index fund sacrifice profits in one company if the corresponding benefits for other portfolio companies are not reflected in their stock price? Underpricing of climate risk means underinvestment in climate mitigation.

Index Funds Give Very Low Weight to the Distant Future

Moreover, index funds assign a very low weight to the benefits of climate mitigation that are expected to occur in the distant future. While most experts believe that society should discount intergenerational climate damage at a rate between 1 percent and 3 percent, stock investors like index funds typically use a discount rate of 7 percent or higher. Such a high discount rate results in massive underinvestment in climate mitigation.

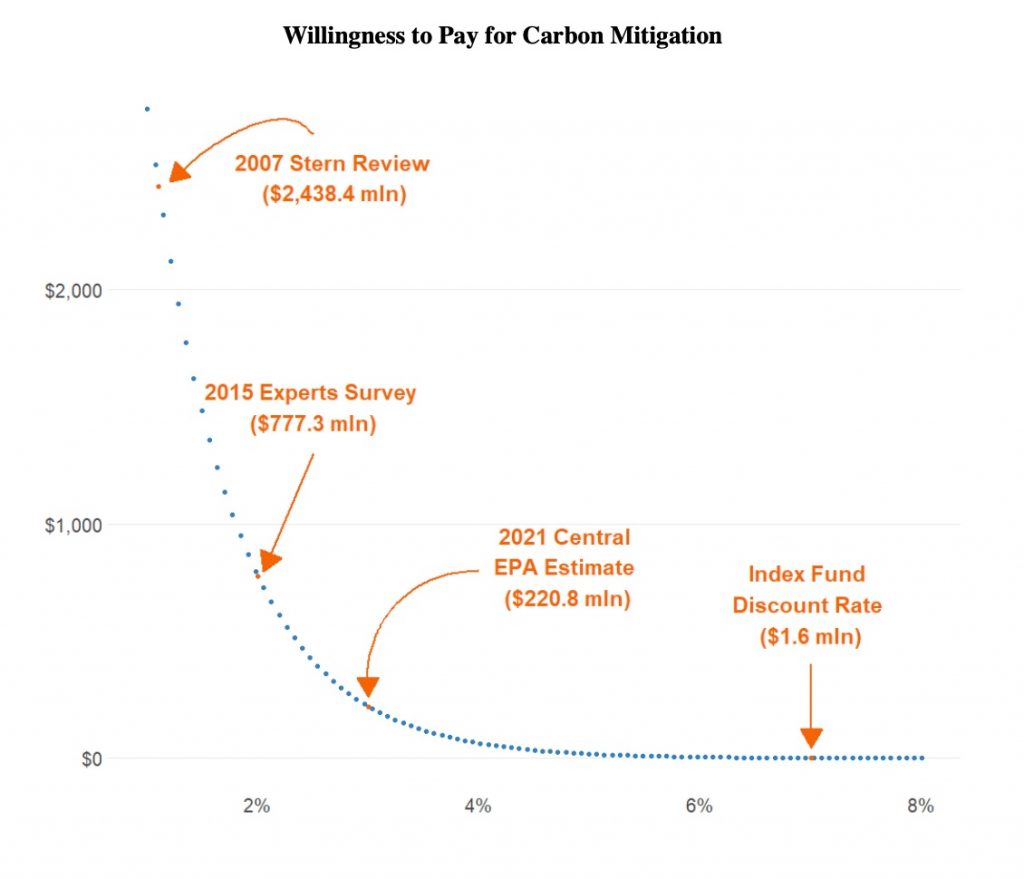

To illustrate, the figure below shows the maximum amount that an index fund that “owns 1 percent of the economy” would be willing to pay in 2021 in order to produce $1 trillion climate benefits in 2150. If the fund used the 1.1 percent discount rate proposed by the Stern Review—a seminal work on the economic effects of climate change, published in 2007—it would be willing to pay up to $2.5 billion. If it used a “consensus” social discount rate between 2 percent and 3 percent, it would be willing to pay a sum between $221 million and $777 million. But index funds discount future cash flows at 7 percent (or even more). Therefore, in this hypothesis, the fund would not pay more than $1.6 million for the proposed mitigation measure—a very small sum.

The simulation assumes that the index fund “owns 1 percent of the economy” and therefore captures 1 percent of all the positive externalities of the mitigation measure. The vertical axis reports figures in millions of dollars.

Index Fund Portfolios Are Biased

Let’s suppose for a moment that a given carbon mitigation measure will produce a large stock market gain even with a 7 percent discount rate. For example, let’s suppose that the measure would reduce the stock value of oil companies by $1 trillion but will increase the stock value of all other public companies by $1.3 trillion—a net gain of $300 billion. What would the index funds that invest in ExxonMobil do? Would they push ExxonMobil to adopt such a measure?

Surprisingly, the answer is not as straightforward as many would think. Index funds are not real “universal owners”: they invest only in subsets of the market and the specific composition of their portfolios inevitably affects their incentives with respect to climate change.

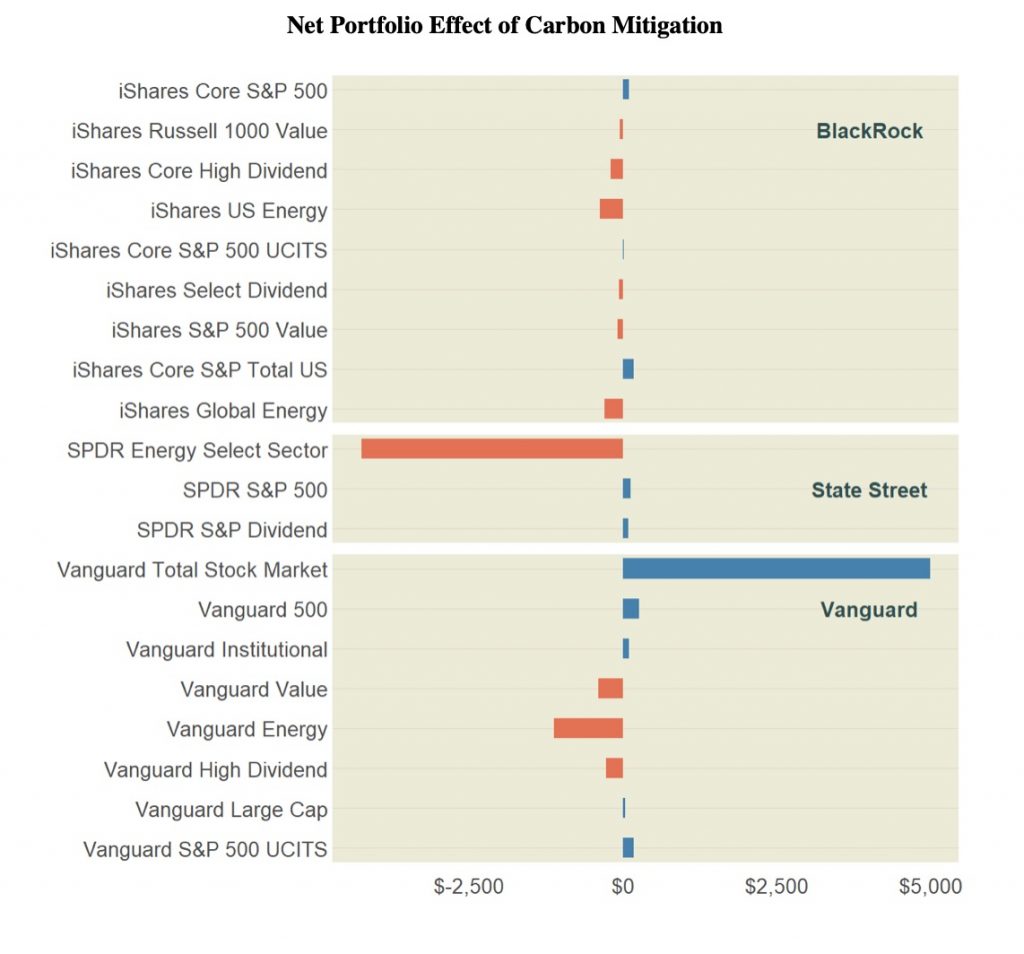

The figure below simulates, with some minimal assumptions, the net portfolio effect of the above mitigation measure on the 20 “Big Three” index funds with the largest holdings in ExxonMobil. While some funds would make substantial gains—for example, Vanguard Total Stock Market, which invests in more than 4,000 companies—other funds would take a hit—for example, those specialized in the energy sector.

Interestingly, only for Vanguard the aggregate net effect of the proposed mitigation measure would be positive. For BlackRock and State Street the measure would result in a net loss despite the huge positive effect for “the whole market.”

Another form of portfolio bias regards geography. Even index funds with a very broad market base are biased in favor of richer countries and therefore do not internalize the relatively larger losses that poorer countries are expected to suffer from climate change.

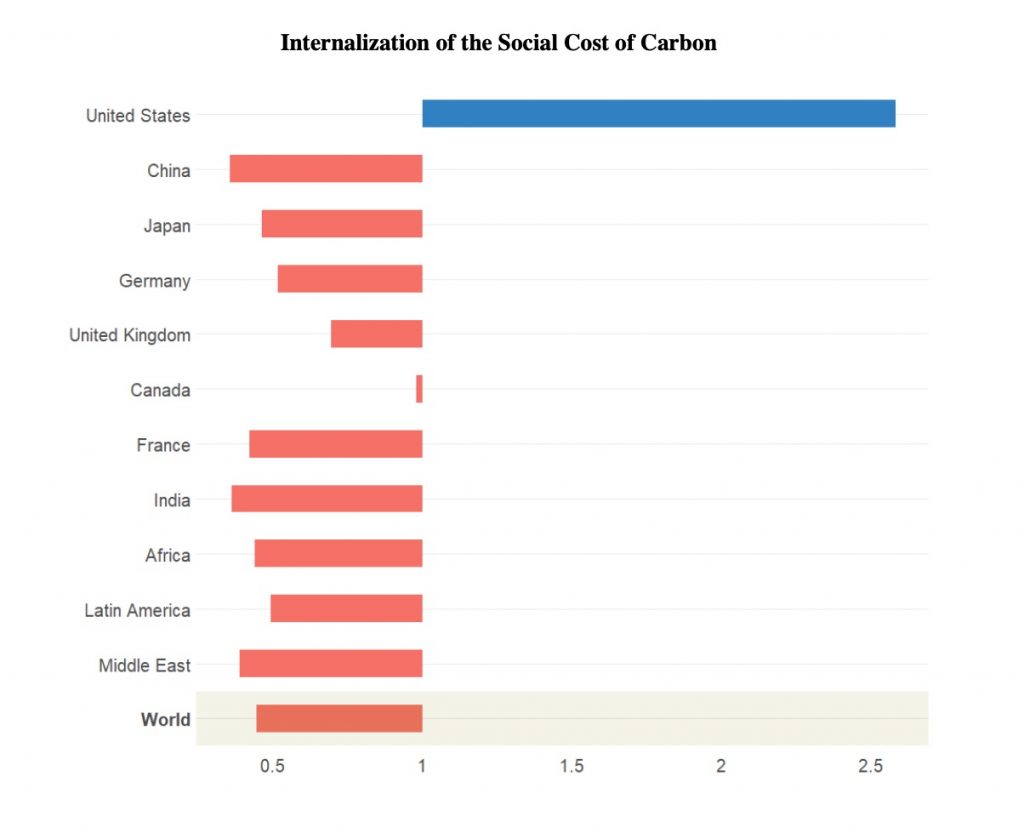

For example, the United States accounts for 24 percent of the global economy and India accounts for 5 percent of the global economy. However, 63 percent of the aggregate revenues of the portfolio companies of the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund come from the United States and only 1 percent come from India. Since India is expected to suffer significantly larger climate losses than the United States, the portfolio bias towards the Unites States means that the fund internalizes only a fraction of the global cost of carbon and therefore is incentivized to underinvest in climate mitigation. The figure below simulates this effect. A value greater than 1 means that the fund internalizes more than its proportional share of the local social cost of carbon. A value smaller than 1 means that the fund internalizes less than its proportional share of the local social cost of carbon. As the figure shows, Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund internalizes less than half of the world’s social cost of carbon.

Fraction of country-level social cost of carbon internalized by Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund, assuming that an index fund internalizes the social cost of carbon of a given country in proportion to the local revenues of its portfolio companies relative to the size of the local economy (GDP). Data on country-level revenues were collected from FactSet GeoRev as of July 6, 2021. Data on country GDP were collected from the World Bank database and refer to 2019. Estimates of country-level social cost of carbon are taken from Richard Tol (2019).

Portfolio Primacy Creates Serious Fiduciary Conflicts

Even if index funds did have strong incentives to become climate stewards, however, the implementation of this strategy would prove extremely problematic from a fiduciary standpoint. Portfolio primacy creates unsolvable fiduciary conflicts on multiple levels: between fund managers and fund beneficiaries; between influential shareholders (such as the “Big Three”) and undiversified shareholders; between corporate directors and the individual company.

As we have seen, climate mitigation might benefit some funds and damage other funds managed by the same institution, thus creating conflicts of interest within the fund family. Furthermore, portfolio primacy calls for decisions that may reduce firm value in order to benefit the portfolio of some large investors, to the detriment of minority shareholders who are not maximally diversified. All these aspects clash against the current structure of fiduciary and corporate law.

“On a close examination, the promise of portfolio primacy appears unreliable. Given the urgency of the climate threat and the significant limits of portfolio primacy, policymakers should focus their efforts on altering the incentives of individual companies with traditional regulatory tools.”

Most Firms and Carbon Emitters Are Partially or Totally Shielded from Index Fund Stewardship

Finally, even if all the above obstacles disappeared and index funds started pressuring companies on climate mitigation in a serious way, we should not overestimate the impact of their stewardship on a global scale. To begin with, most firms around the world, including most carbon emitters, are partially or totally insulated from the influence of index funds because they are privately held, are owned by state governments, or have a controlling shareholder.

Furthermore, in a growing number of large US public companies there is a CEO-Founder or other main shareholder with the largest equity stake and the most voting rights. For example, half of the twenty largest companies in the S&P 500 have a controlling or influential shareholder who has no financial incentive to reduce the value of their company (which often represents most of their personal wealth) in order to create a portfolio gain for the Big Three.

Finally, even public companies with a dispersed ownership could easily go private or sell their most carbon-intensive assets to private owners, thus shielding them from index fund stewardship. When we take account of this reality, which involves most firms around the world and many of the largest US firms, the sphere of influence of index funds appears quite narrow.

Some Policy Implications

Portfolio primacy has a powerful appeal. It offers a tool to fight climate change without intrusive government regulation and it argues that index funds are eager to fight climate change not because of prosocial and altruistic inclinations, which many people find hard to believe, but because of mere financial incentives.

On a close examination, however, the promise of portfolio primacy appears unreliable. Given the urgency of the climate threat and the significant limits of portfolio primacy, policymakers should focus their efforts on altering the incentives of individual companies with traditional regulatory tools (carbon tax, cap-and-trade systems, prescriptive regulation) rather than rely on the portfolio incentives of index funds.

The full paper “The Limits of Portfolio Primacy” is available on SSRN.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.