A large and growing body of research demonstrates that employer concentration affects the wages of many American workers. Antitrust is an important tool in mitigating labor market power, but it isn’t the only one policymakers should use.

Does antitrust have a labor market problem? The last few years have seen growing interest among academic scholars in the causes and effects of concentration in US labor markets. Concurrently (and not unrelated), there has been an explosion of interest among policymakers and the general public in the impact that firms with market power may have on wages and working conditions. What do the data say regarding employer concentration and its effect on workers? Is antitrust in its current form equipped to address issues related to labor market power? In an attempt to answer these questions and more, we have decided to launch a series of articles on antitrust and the labor market.

If workers have few employers to choose from, how much does this affect wages? And how can or should policy respond? In the past, employer concentration—the phenomenon where workers have only a few employers to choose from—was thought to be a niche issue, confined to a few factory towns. But in recent years, researchers have documented high levels of employer concentration across much of the US labor market. These early papers—alongside a large and growing body of more recent work—illustrate that local labor markets with higher levels of employer concentration also have lower wages, suggesting that employer concentration might be suppressing wages by increasing employers’ monopsony power.

This correlation alone can’t prove causality. After all, it is possible that local labor markets with low productivity in a certain industry may have few firms in that industry and also low pay for the workers, creating a spurious correlation between high employer concentration and low wages which isn’t causal from one to the other. As a result, a number of research papers use different empirical strategies to estimate a causal effect of employer concentration on wages. Findings from these studies suggest that there is, indeed, a causal effect of employer concentration on wages. The exact magnitude of that causal effect depends on the study and estimation strategy.

In our recent working paper “Employer Concentration and Outside Options,” jointly written with Bledi Taska, we attempt to estimate the causal effect of employer concentration on wages across nearly the entire US labor market over 2013-2016. Using plausibly exogenous variation in employer concentration local occupational labor markets, we estimate that moving from the median level of employer concentration to the 95th percentile—and holding all else equal—on average leads to around 3 percent lower wages.

Should policy respond? And if so, how? One promising avenue is antitrust, which is explicitly focused on responding to market power. Until recently, US antitrust authorities had rarely considered labor markets in merger scrutiny or lawsuits against anticompetitive behavior. But more recently, scholars, including Ioana Marinescu and Herbert Hovenkamp, and Suresh Naidu, Eric Posner, and Glen Weyl, have proposed that antitrust authorities should use measures of employer concentration when screening for possible anticompetitive effects of mergers and acquisitions, as they already do in product markets. In cases where a merger or acquisition would increase employer concentration beyond a certain critical threshold, further scrutiny of the M&A activity would be triggered to decide whether or not it should be allowed to go ahead.

Our research—which finds a negative causal effect of employer concentration on wages—would tend to support this policy proposal, but with a caveat. In much of the work on employer concentration, labor markets are defined as an occupation within a local area. But, as antitrust authorities and scholars are aware, the definition of a market is always difficult. What matters for workers’ wages is the concentration of employers across their entire labor market, because higher concentration reduces the availability of feasible jobs and the scope of their labor market may be broader than just jobs in their specific occupation. To understand the scope of workers’ true labor markets, in our paper we use 16 million US workers’ resumes to construct fine-grained data on workers’ job mobility flows within and across occupations. We find that for many occupations, the labor market is indeed very broad.

Think about cashiers, for example: When they look to leave their current employer, they will likely look for other jobs as a cashier but will also look for work in other occupations, for example as retail salespersons, customer service representatives, secretaries, or waiters and waitresses. When cashiers change jobs, our data suggest that nearly a third of the time they find a new job not as cashiers but in a different occupation altogether. This has implications for how we’d expect employer concentration to affect cashiers. Imagine employment for cashiers was very concentrated: most of the cashier jobs in the local area are with the same employer, like a large department store. A cashier leaving her job at the large department store may not be able to find an equivalently good job as a cashier in some other store, but she may still be able to find an equivalently good job in a different occupation and industry.

On the other hand, think about registered nurses. Our data suggest that they very rarely leave their occupation, and when they do, they almost always move to other health care occupations. This means that if most of the nursing jobs in their local area are offered by the same employer—for example, the only hospital in the area—nurses have a limited “outside option.” That is, if they leave their current employer, it will be difficult for them to find an equivalently good job somewhere else, because they don’t have good options outside their occupation (and the lone hospital in the area is the major employer within their occupation). This would lead us to expect that employer concentration among retail stores would be less of a problem for cashiers than employer concentration among health care providers would be for registered nurses.

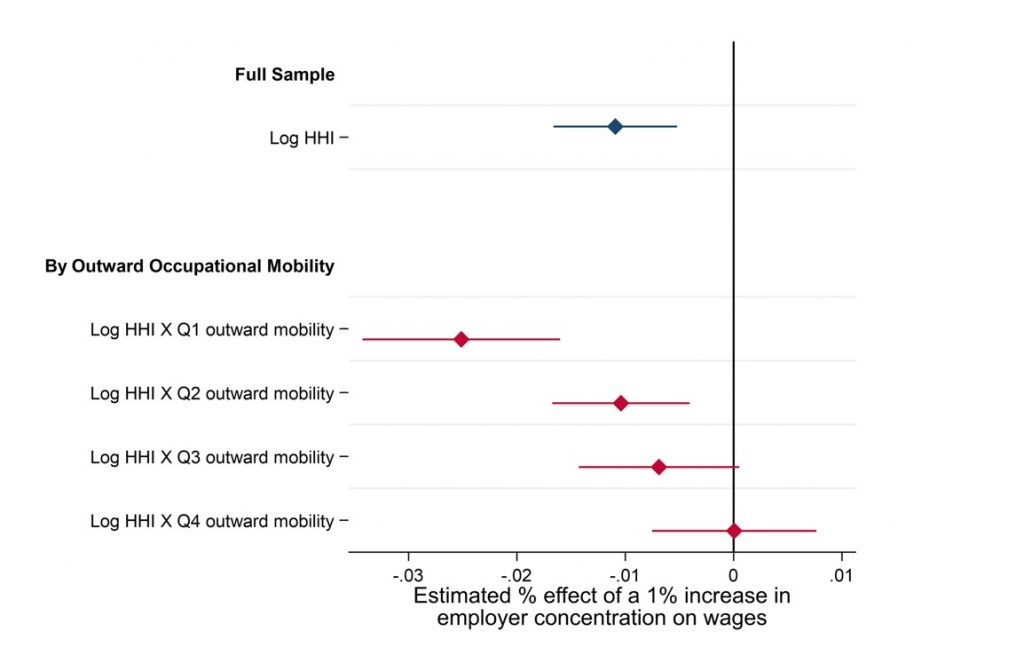

Indeed, this is what we find empirically: For occupations with limited occupational mobility—like the registered nurses in the prior example, who rarely move to a different occupation—we find that employer concentration matters a lot for wages (See Figure 1). Specifically, our results suggest that for workers in the lowest quartile of outward mobility, moving from the median level of employer concentration to the 95th percentile reduces average hourly pay by between 4 and 8 percent. This may sound small, but the dollar amounts are not trivial: a 4 to 8 percent reduction in pay would mean roughly $3,000 to $6,000 less income per year for a typical registered nurse, or $1,400 to $2,700 less per year for a typical pharmacy technician, for example.

On the other hand, for occupations with high occupational mobility who can find other jobs outside their own occupation more easily, like the cashiers in the prior example or like bank tellers, retail salespersons, or telemarketers, we find no detectable effect of employer concentration within their occupation on the wage.

Work by Elena Prager and Matthew Schmitt, looking at the effect of hospital mergers on wages of different workers, comes to a similar conclusion. Prager and Schmitt find that mergers that increase local hospital concentration lead to big wage reductions for nursing and pharmacy workers, and medium-sized wage reductions for administrative employees and social service workers at the hospitals in question. On the other hand, they find very little effect of hospital mergers on the wages of food service, laundry, and janitorial workers at hospitals. That would be consistent with our argument above, that these workers’ labor market extends to include jobs outside the health care sector.

These results have implications for how antitrust should respond to labor market concentration. In particular, they suggest that using employer concentration measured at the level of local occupations or industries to screen M&A activity and target antitrust enforcement risks missing the target in important ways. It might lead to excessive scrutiny for anticompetitive issues in labor markets where there is unlikely to be an effect. It might also divert authorities’ attention away from labor markets where levels of concentration are not particularly high, but where low levels of mobility outside the occupation or industry mean that the wage effects of even that moderate level of employer concentration could be substantial.

As a result, we recommend that antitrust authorities do use employer concentration as a screen for possible anticompetitive effects of M&A activity, but also consider the possibility for outward mobility in the occupation in question. This may seem like a small tweak, but it could have major implications.

“For occupations with limited occupational mobility, we find that employer concentration matters a lot for wages.”

Increasing antitrust scrutiny of labor markets to respond to labor market concentration is an important step. Nonetheless, it’s also important to note its limitations.

First, employer concentration matters for some workers, but the bulk of the evidence so far suggests that it can only explain a very small share of aggregate patterns or trends in wages, wage growth, or inequality. In our paper, we estimate that around 10 percent of the US workforce see wage effects of 2 percent or more from being in labor markets that are more concentrated than average. These are mostly people in low-population-density areas, in concentrated industries, and/or in low outward mobility occupations, like the canonical example of rural hospitals. 10 percent is a non-trivial share of people, and certainly big enough to justify a policy response. At the same time, it is also not a big enough share to have much of an impact on aggregate inequality. In addition, work by Kevin Rinz, and by David Berger, Kyle Herkenhoff, and Simon Mongey, illustrates that at the level of local industries, employer concentration has on average been declining, not rising, over recent decades. That means that changes in employer concentration are very unlikely to be able to explain trends of rising inequality over time.

Second, most employer concentration doesn’t arise as a result of mergers or acquisitions, the kind of activity most likely to be subject to antitrust scrutiny. In many cases, employer concentration arises as a result of the growth of already-large firms or the decline of small firms. In these cases, employer concentration may be suppressing wages, but merger scrutiny is not the right tool to respond.

Third, employer concentration may create employer power, and this likely suppresses wages relative to the wage that the employer could feasibly pay—but it does not necessarily suppress wages relative to a counterfactual where those large firms were broken up. This is because in some cases, larger firms may be more productive or more profitable than equivalent smaller firms—think, for example, of factories or hospitals, which require a certain size to operate efficiently. When antitrust authorities consider whether a merger or acquisition will have harmful labor market effects, they will need to consider in tandem both the possible wage suppressive effects of the increase in employer concentration and the possible wage-increasing effects of any increase in productivity the M&A would bring. It may be the case that, in some cases, on net workers are better off, even if the merger or acquisition increases employer concentration.

These limitations do not mean that there is nothing else that can be done in the cases where antitrust isn’t the appropriate tool: there are other ways in which policy can respond to employer concentration. For example, policy could seek to raise wages for affected workers through minimum wages, or perhaps wage boards that set pay for workers in specific industries or occupations higher up in the wage distribution. Or, policy could give workers countervailing power to bargain directly with large employers, whether through increased support for firm-level unions (the current model of collective bargaining in the US), or whether through the type of sectoral bargaining that is more common in much of continental Europe.

Policymakers can also seek to reduce the effects of employer concentration themselves by increasing the scope of workers’ labor markets: the less any one employer matters for your wage, the more choice of employers you have. This could be by removing barriers to mobility between firms (for example, by restricting the use of non-compete agreements), between occupations (for example, by removing overly restrictive occupational licensing requirements), and between places (for example, by increasing the supply of affordable housing in high-wage cities).

In conclusion: a large and growing body of research demonstrates that employer concentration affects the wages of many American workers. Antitrust is an important, and appropriate, venue for policy response. If targeted judiciously towards the labor markets where employer concentration is a true problem, it could have a meaningful impact on wages for many workers. At the same time, antitrust will not always be the appropriate response to employer concentration, and policymakers should also consider responses that increase workers’ wages directly, that empower workers to bargain with their employers, and that increase the scope of workers’ labor market options.

Disclosure: This work used proprietary data on resumes and job vacancies provided by Burning Glass Technologies, Inc. The work was supported in part with a Doctoral Grant from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.