A series of academic studies in recent years highlighted the fact that labor markets are often highly concentrated and that employers use anticompetitive methods to suppress wages. Since then, antitrust law has taken some steps to fix its labor market problem. But a question remains whether the courts, so far the biggest impediment to any reform, will be more receptive in light of the new evidence.

Does antitrust have a labor market problem? The last few years have seen growing interest among academic scholars in the causes and effects of concentration in US labor markets. Concurrently (and not unrelated), there has been an explosion of interest among policymakers and the general public in the impact that firms with market power may have on wages and working conditions. What do the data say regarding employer concentration and its effect on workers? Is antitrust in its current form equipped to address issues related to labor market power? Attempting to answer these questions and more, we have decided to launch a series of articles on antitrust and the labor market.

Three years ago, I wrote in these pages that antitrust had a labor market problem, arguing that the FTC should focus on labor monopsony. Indeed, this problem is the subject of my new book, How Antitrust Failed Workers. As I have pointed out, there is a vast gap in antitrust litigation oriented toward product markets (lots) and labor markets (hardly any), while no reason as a matter of theory or evidence to believe that anticompetitive behavior occurs more frequently in product markets than in labor markets. That gap had hardly even been noticed or commented on in the past, confirming Adam Smith’s observation that employer collusion is ubiquitous but invisible. But the veil of invisibility has been lifted in recent years by several studies that reveal that labor markets are frequently highly concentrated and that employers use anticompetitive methods to suppress wages. And in the last couple years, antitrust law has taken some steps to catch up with labor market cartelization—baby steps, to be sure, and not enough. But progress nonetheless.

Markets are central to all modern economies, and markets enhance well-being only when they are competitive. Antitrust law has long stood as the bulwark against anticompetitive behavior by cartels, monopolists, and other product-market bullies, keeping prices low and output high. For reasons lost to history, however, antitrust law has rarely been used against labor-market bullies like employer cartels and labor monopsonists. This means that any rational, profit-maximizing firm will look for opportunities to cartelize labor markets where the sheriff dozes, while treading cautiously in product markets where the sheriff keeps a watchful eye. So while antitrust law forces firms to charge low prices in some instances, the wages from which consumers pay those prices may be suppressed by the monopsonistic behavior of the same firms. Theory suggests that weak antitrust enforcement may help account for labor’s low share of economic output, inequality between investors and people who depend on wages, and economic stagnation, though empirical work on these questions is ongoing.

When I wrote in 2018, some then-recent working papers (now published), including studies by José Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall Steinbaum and by Efraim Benmelech, Nittai K. Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim, revealed that many thousands of labor markets were extremely concentrated. Evan Starr and various coauthors showed that anticompetitive covenants not to be compete were far more common than people had realized, while Alan Krueger and Orley Aschenfelter found that brand-name franchises like McDonald’s frequently employ no-poaching agreements. More recent studies have confirmed these findings using various datasets and methods. Elena Prager and Matt Schmitt, for instance, examined hospital mergers and found that when hospitals merge in concentrated labor markets, wage increases decline for medical professionals but not for hospital workers with opportunities outside hospitals (for example, cafeteria workers). A multitude of follow-up studies have found consistent results.

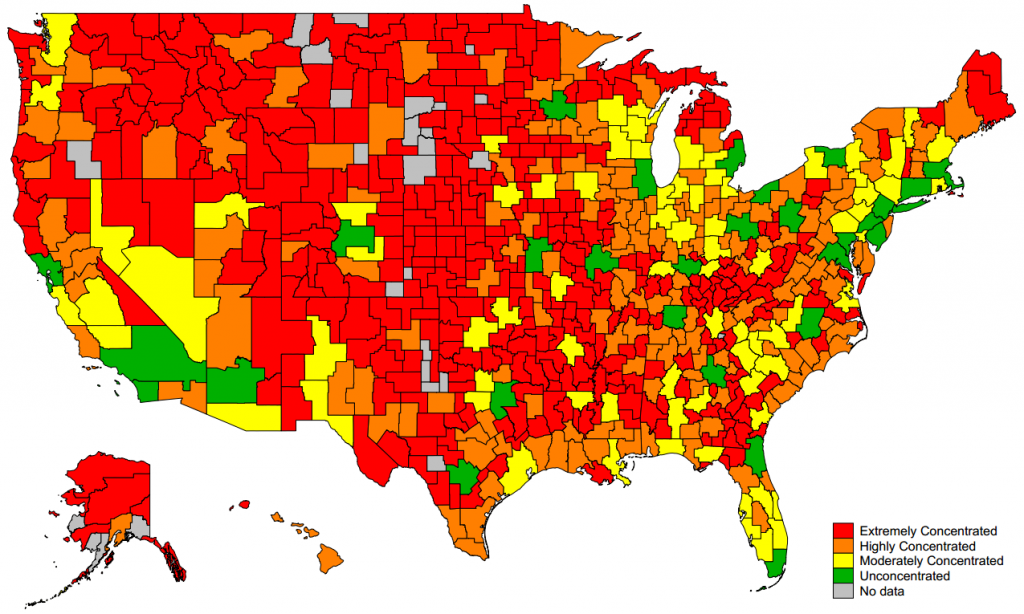

The figure above, taken from José Azar, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall Steinbaum, shows the extent of labor concentration in the United States. The country is divided into commuting areas—which can be taken to be rough proxies for labor market areas. The areas colored red and orange exhibit extremely high average labor market concentration, high enough that under Justice Department standards, any mergers that increased labor market concentration would likely be blocked. These areas tend to be rural and suburban, thinly populated with workers as well as employers, but tens of millions of people are affected. Some simple calculations suggest that high labor market concentrations cost many workers of moderate income thousands of dollars in wages every year.

Antitrust litigation relating to labor markets circa 2018 was virtually nil. Over the preceding decades, only a handful of cases seriously challenged anticompetitive labor market practices, including no-poaching agreements and wage-fixing agreements. The most important such case was the 2010 lawsuit by the Justice Department charging that Silicon Valley companies like Apple and Google had agreed not to poach each other’s software engineers. Piggyback private litigation obtained a settlement of more than $400 million. There had also been a small number of cases that challenged sports leagues for suppressing the wages of athletes. I do not believe there has ever been a successful lawsuit against a labor monopsonist for obtaining or protecting a labor monopsony—nothing comparable to the blockbuster monopoly cases of the past like Standard Oil (1911), Alcoa (1945), AT&T (1982), and Microsoft (2001).

Litigation since 2018 provides some grounds for optimism that antitrust law may overcome its labor market problem. Krueger and Aschenfelter’s study spurred attorneys general in Washington, New York, and other states to sue the franchises, most of whom settled by agreeing to drop the no-poaching clauses from the franchise agreements. Private litigation against franchises, including McDonald’s, Burger King, and Domino’s, has also begun. Government warnings and hand-wringing has finally led to some action: The FTC filed a comment last year opposing a hospital merger in Texas because of its labor market effects. The Justice Department has brought three criminal indictments against executives who entered no-poaching or wage-fixing agreements. Some other major private litigation has occurred, including lawsuits against Duke University and the University of North Carolina for agreeing not to poach one another’s faculty, and against large meat processors for fixing wages.

“FOR REASONS LOST TO HISTORY, ANTITRUST LAW HAS RARELY BEEN USED AGAINST LABOR-MARKET BULLIES LIKE EMPLOYER CARTELS AND LABOR MONOPSONISTS. THIS MEANS THAT ANY RATIONAL, PROFIT-MAXIMIZING FIRM WILL LOOK FOR OPPORTUNITIES TO CARTELIZE LABOR MARKETS WHERE THE SHERIFF DOZES, WHILE TREADING CAUTIOUSLY IN PRODUCT MARKETS WHERE THE SHERIFF KEEPS A WATCHFUL EYE.”

But problems remain. In my earlier piece, I listed various reasons why labor-oriented antitrust cases have been so rare. Wages, benefits, work conditions, noncompetes, and other elements of the employment relationship that are essential to an antitrust case are not always publicly available information. Class actions are hampered by the small size of many labor markets and the frequently idiosyncratic nature of employment relationships. Arbitration clauses inserted in employment contracts may also block class actions. Without the ability to identify labor market violations and construct classes, lawyers cannot finance class actions, while individuals claims are almost never financially viable. And increasing judicial hostility over the last several decades to all kinds of antitrust claims has led to a narrowing of the types of claims that can be brought, and the types of people who can bring them.

Recent litigation has exposed additional challenges. Because of the infrequency of labor market cases, few judicial precedents offer guidance that litigants and judges normally rely on, generating uncertainty and confusion. And some judges seem to be uncomprehending or hostile. For example, in Llacua v. Western Ranch Association, a class of sheepherders sued an organization set up by ranchers to recruit workers from foreign countries and allegedly fix their wages at the legal minimum. The plaintiffs lost, and on appeal, in 2019, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. In response to the argument that it was hardly a coincidence that all workers, regardless of where they were located, were paid the absolute lowest possible legal wage under state or federal minimum wage laws, the Court said that “Assuming a sufficient supply of qualified labor is available at this wage, no rancher would be logically inclined to offer more.” The Court forgot that in a competitive market, employers would bid wages up. The Court also expressed doubt that firms would help their competitors by agreeing to a low wage, ignoring the central antitrust principle that cartels are mutually beneficial.

Private no-poaching cases have also faced headwinds. Franchisors contract separately with each of their franchisees, and the franchisees do not contract with each other. The no-poach clauses in the franchise contracts are thus “vertical,” although some franchise agreements give each franchisee the right, as a third-party beneficiary, to enforce the no-poach clause against other franchisees (“horizontally”). The Justice Department under the Trump administration took the position that this minor distinction should play a crucial role in determining the standard for evaluating whether the clauses violate the antitrust laws, based on doctrine that holds that vertical arrangements are normally evaluated under the rule of reason, while horizontal arrangements are subject to a greater level of scrutiny. This shallow formalism provides a roadmap for franchisors to minimize the risk of antitrust scrutiny—simply by taking on the burden of enforcing no-poach clauses themselves rather than delegating the power to franchisees.

An opinion filed last July in the franchise case of Deslandes v. McDonald’s illustrated other obstacles to labor market cases. The Court denied class certification for numerous reasons, and without a national class, plaintiffs will have difficulty financing the enormous costs of litigation. The Court pointed out the labor markets are local, implying that plaintiffs will need to bring hundreds of low-value class actions rather than a single national class action. While it is true that labor markets are local, variations in local labor markets can be handled with an econometric model. A national class action is appropriate where, as here, a single national policy—the franchisor’s decision to bind all franchisees to no-poach clauses—is at the center of the case.

The Court also accepted a defense expert’s questionable claim that the allegations against McDonald’s “do not make economic sense.” The expert argued that a no-poaching arrangement reduces the amount of workers at each franchisee, resulting in fewer burgers being sold, and lower royalties for McDonald’s, which is paid a percentage of revenues (which decline in the number of burgers), not of profits (which rise as labor costs fall). McDonald’s would not insist on no-poach clauses that enriched franchisees at its own expense.

But, in fact, McDonald’s makes most of its money by renting land to franchisees and charging them a franchise fee. If McDonald’s enables higher profits for franchisees with the no-poach clause, then demand for franchises increases. McDonald’s can sell more franchises at higher prices taking the form of higher rents and franchise fees. The Court also bungled Gary Becker’s theory of human capital, arguing that the no-poach clause may be justified for encouraging franchisees to invest in relationship-specific training. But relationship-specific training does not require hiring constraints since by definition it is of no value to other firms. And while the court might have meant that restaurants will not train employees who may go to work for other restaurants within the McDonald’s franchise, McDonald’s could internalize this cost by requiring franchisees that poach employees to compensate the original employer for training costs, which are likely trivial for such low-skilled work.

Having nonetheless credited the expert’s argument, the Court held that the rule of reason applies to the case rather than “quick look”—meaning, the case will be a lot harder for the plaintiffs to win. The Court also (incorrectly) held that because the rule of reason applied, the plaintiffs are required to define the labor market(s) at a more rigorous level, and that fed into the denial of class certification. Ironically, the court also held that the rule of reason applied because it did not have “enough experience with no-hire provision of franchise agreements,” but if other courts follow this one and dismiss franchise no-poaching cases at an early stage in the proceedings so that trials are never held, no such experience will ever be gained.

But it seems more likely that as new ideas and information disseminate through the antitrust community and the courts, the judiciary will become more receptive to labor-antitrust claims. Indeed, the Supreme Court itself ruled just last spring that the NCAA had violated the antitrust laws by regulating schools’ compensation of student athletes with non-cash education-related benefits like scholarships. The decision was narrow and long in coming. But coming from the Supreme Court, it ought to spur lower court judges to help antitrust overcome its labor market problem.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.