In her new book Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity, Harvard Professor Claudia Goldin traces how generations of women have responded to the problem of balancing career and family. The following excerpt explores how pharmacists are one of the handful of professions to achieve gender equality.

Not only is the occupation of pharmacist egalitarian; it is also highly lucrative. Relative to women in all other occupations, female pharmacists rank fifth (out of almost five hundred occupations) in terms of their median earnings, as reported in the US census for full-time, full-year workers. (Lawyers are seventh among women.) Female pharmacists don’t just have high incomes relative to other comparably educated women; they also earn almost the same as male pharmacists when adjusted for hours of work.

What accounts for the gender equality among pharmacists yet the large inequity remaining in the legal field? After all, both professions have experienced similar increases in the fraction of women entering the field, and both require specialized post bachelor’s training, in which women have thrived.

The answer lies in the very structure of the work. These occupations once shared similar characteristics. Long and irregular hours had been an important feature of the lives of both pharmacists and lawyers. Each occupation involved a high degree of self-employment and carried the risk that ownership always entails. Whereas these features still define the situation of lawyers today, none of them applies to modern pharmacists.

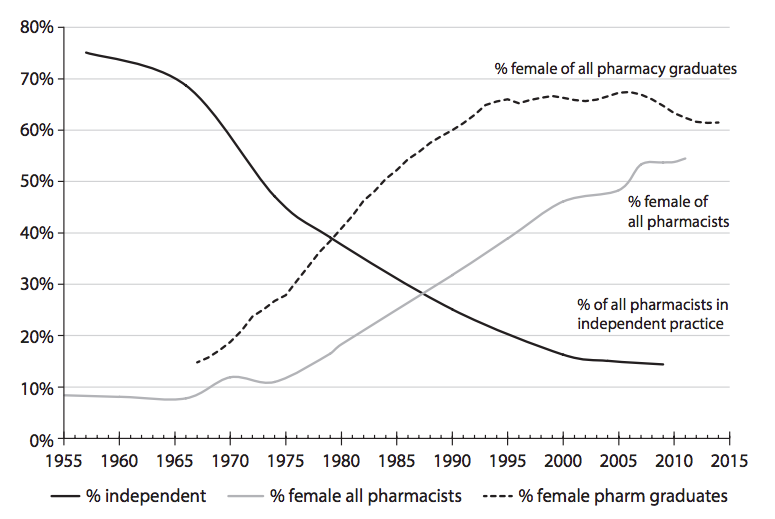

Vials is a recent, short-lived, funny sitcom set in an independent pharmacy called Gateway Drug. The store is owned by a cantankerous pharmacist named Rich and run by various technicians and Rich’s rebellious daughter Lisa, a newbie pharmacist. A half century ago, pharmacies like Gateway Drug were the main way consumers got their prescriptions filled and their drugstore needs met. The pharmacists and pharmacy owners of the past were almost all men. In 1965, female pharmacists constituted less than 10 percent of all pharmacists (see figure 9.3) and were usually employed by a male pharmacist who owned the store. In that year, about 75 percent of all pharmacists were either owners of independent practices or were their employees (the other 25 percent worked in chains, hospitals, and the like). The female pharmacists earned 67 cents on the male pharmacist dollar, largely because they didn’t own the stores.

Pharmacists who worked longer hours in those days (when even pharmacists were watching Perry Mason on TV) earned considerably more per hour than those who worked fewer hours. The self-employed were far more highly remunerated than were employees. Women with children must have earned far less than those without children, even if they worked the same hours, because they were unable to work particular hours on demand. The occupation of pharmacist in the midtwentieth century seems a lot like some occupations in the financial sector today, and like today’s lawyers and accountants.

The products that pharmacies sold and the services they offered were somewhat different from today’s. Drugs were often compounded specifically for the client, and the relationship between pharmacist and client was more intimate. Pharmacists could even be roused at late hours to fill an urgent prescription for a familiar client.

Then things began to change. No longer were pharmacists distinct from one another. They didn’t give as much personal service, and they didn’t have to memorize their clients’ individual medical needs. I doubt that anyone reading this page has gone to the pharmacy in recent years, handed over a refill request, and demanded that the pharmacist to whom they originally gave the prescription be the one to fill it. Yet when we see our tax accountants and divorce lawyers, we expect to deal with a particular professional, not their officemate.

What changed in pharmacies? Drugstores became big business, increasing both in size and in scope of operations across the twentieth century. From the 1950s to today the fraction of independent pharmacies plummeted, and with that transformation, the fraction of pharmacists working in independent practices dropped drastically too. Changes in our health care and health insurance systems reinforced these trends and produced an increase in the share of pharmacists working in hospitals and in mail-order pharmacies.

Each of these shifts reduced the number of self-employed pharmacists and increased the fraction working as employees of corporations. Whereas the corporate sector isn’t generally viewed as an agent of progressive change, in this case it played exactly that role. The shift of pharmacies to the corporate sector meant that ownership was no longer relevant to a pharmacist’s job. Since men had been the owners and women were primarily their assistants, the shift meant that men and women could be more equal as pharmacists. The person receiving the net profits from the enterprise was no longer the male pharmacist. It was the stockholders.

Several other transformations reinforced these changes. Drugs became far more standardized, and, with few exceptions, compounding was no longer needed. Information technology gave any pharmacist access to the list of all the prescription drugs a client was taking, and that knowledge allowed him or her to give appropriate advice on drug interactions to any client.

Personal contact with the pharmacist was no longer important for an individual customer’s health and well-being. Late-night pharmacies meant that all pharmacists did not have to be on call. A close relationship with your pharmacist was no longer necessary to give you late night entrée to the drugstore.

Throughout these transformations, the job of a pharmacist did not become easier, and the position did not become less professional. Most recently, pharmacists have been called into the frontlines of managing and administering part of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. In fact, drugs and medications have become far more complex than they were fifty years ago, and pharmacists have to know considerably more than they did in the past. The educational demands in the training of pharmacists increased. Whereas an undergraduate degree in pharmacy plus one year (and the passing of boards and some experience) was once sufficient to become a practicing pharmacist, since the early 2000s a six-year PharmD degree (two undergrad years and four grad years), plus boards and practical experience, have been required.

Fast-forward to the pharmacies of today. Gateway is an anomaly. Only about 12 percent of pharmacists work for independent local pharmacies. Huge national chains like CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart, and a multitude of hospitals, now employ the majority of pharmacists. Along with mail-order pharmacies, stores like these fill the bulk of our prescriptions.

More than 50 percent of all pharmacy graduates today are women, and that has been the case ever since the mid-1980s. Female pharmacists are no longer the sidekicks of the male pharmacist-owners. They are their equals. Both are primarily employees, not owners. Pharmacists today are largely the personnel of a corporate entity.

“The shift of pharmacies to the corporate sector meant that ownership was no longer relevant to a pharmacist’s job. Since men had been the owners and women were primarily their assistants, the shift meant that men and women could be more equal as pharmacists.”

Together, these changes meant that one pharmacist could easily be substituted for another, and that meant that pharmacists, by and large, did not have to work long and irregular hours. There are, of course, some pharmacists who work evenings, weekends, and vacations—the ones who staff the twenty-four-hour pharmacies, the hospital pharmacies, and those that are mail order—and they often still earn hardship pay. But the midnight owls may be rarer in pharmacy than in other fields where a large fraction of professionals are on call. The main point is that because there is almost perfect substitution, no one pharmacist is worth a tremendous amount more if he or she gives extra time to the job. Yet all are still valued professionals.

As pharmacists became better substitutes for each other, the hourly wage penalty to working part-time just about disappeared. The median female pharmacist now earns around 94 cents on her male counterpart’s dollar. Pharmacy is one of a handful of professional occupations in which there is no discernible part-time penalty. Managers in corporate pharmacies make more money than the nonmanagers, but most of the difference is because they work more hours. The pharmacist who works more hours gets higher pay but doesn’t get much more per hour. Pharmacy pay is just about linear in hours worked—which means that if the number of hours doubles, earnings double (and the same happens for any multiple).

As a result, there is no discernible premium in hourly pay for pharmacists today who work long hours. If Lisa works sixty hours a week, she earns twice as much as a pharmacist who works thirty hours a week. If Lisa, or Della the pharmacist, wants to make more money, she works more hours. But her hourly rate doesn’t change. As we saw, the same is not true among lawyers.

Because working more hours doesn’t make your hourly pay go up, lots of female pharmacists—particularly moms—work part-time. Around one-third of female pharmacists work fewer than thirty-five hours per week when they are thirty years old and continue to do so for at least another decade. And because the occupation is flexible, few pharmacist moms take off a lot of time after they have a child. There are very few breaks in employment for female pharmacists relative to lawyers and financiers.

Yet another surprise about pharmacy is that each of the three big changes—the rise of the corporate sector, the standardization of drugs, and the use of sophisticated information technology—occurred because of reasons having little or nothing to do with the large influx of women into the profession. About 65 percent of all PharmD graduates are now women, as compared with 10 percent in 1970, an increase of 55 percentage points.

Pharmacists today are paid very well, and their incomes have increased relative to those of other professionals. From 1970 to 2010, the income of the median pharmacist—working full-time, year-round—increased relative to that of the median lawyer, doctor, and veterinarian (for male and female professionals). In sum, pharmacists became virtually perfect substitutes for one another. Pharmacy, in consequence, has become a highly egalitarian profession. Earnings are substantial, and pay did not decline as women entered the profession in record numbers, a contrast to the usual notion that when women enter an occupation, earnings plummet.

Excerpted from Career And Family:Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity © 2021 by Claudia Goldin. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Learn more about our disclosure policy here.