Over the last two decades, the share of senior corporate executives holding national political office has increased in the United States as well as some other countries. At least in the case of the US, business politicians are more likely to self-finance their campaigns and to enjoy a fundraising advantage over their opponents. On the balance, the election of business politicians appears to have shifted the balance of power toward corporate interests.

The first two decades of the 21st century have witnessed an increase in the number of business leaders running for (and winning) political office. While Donald Trump is perhaps the best-known business politician, a number of other notable corporate executives have also decided to enter politics. For example, Michael Bloomberg, co-founder of Bloomberg L.P., unsuccessfully ran for US President in 2020, while Jon Corzine, the former CEO of Goldman Sachs, was elected US Senator in 2000 and in 2005 became the governor of New Jersey (Corzine left office in 2010). Prominent international examples include Silvio Berlusconi (Italy), Yulia Tymoshenko (Ukraine), Saad El-Din Rafik Al-Hariri (Lebanon), Thaksin Shinawatra (Thailand), Sebastián Piñera (Chile), and Malcolm Turnbull (Australia), among others.

The growing prominence of business leaders in government has motivated public debate about their effect on policy and raised legitimate concerns that business politicians may unduly shift the balance of power toward corporate interests. To examine whether these concerns are justified, we assemble a dataset on corporate executives’ involvement in US politics and analyze their impact on firms, industries, and legislative outcomes over the last forty years. Here we complement the data collected in our paper with data on business politicians from four other countries: Australia, Germany, Great Britain, and Switzerland.

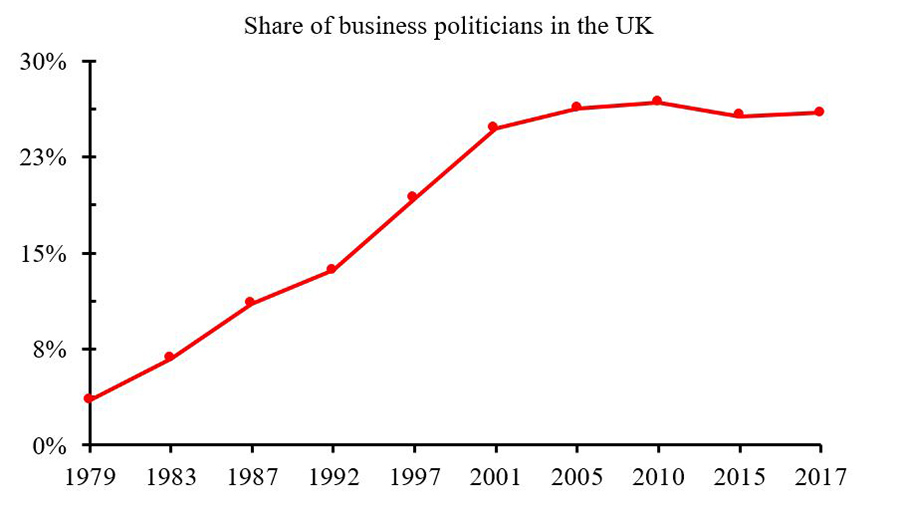

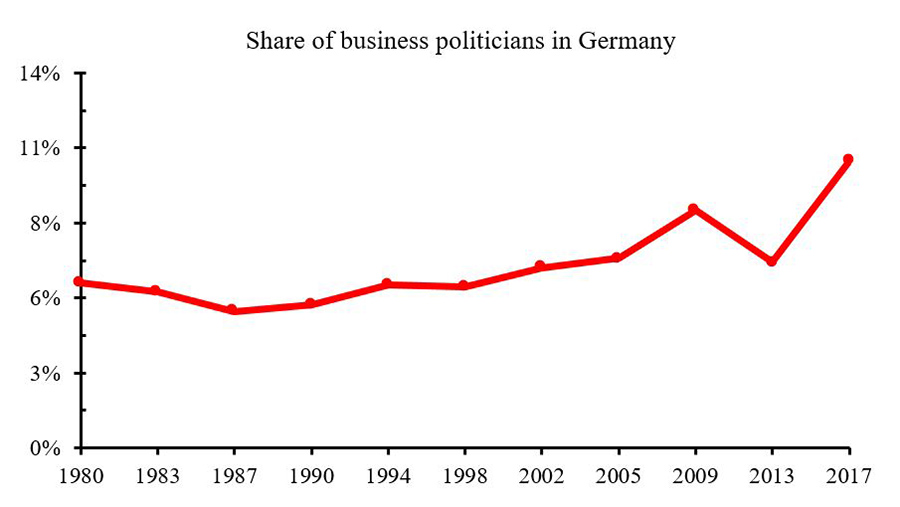

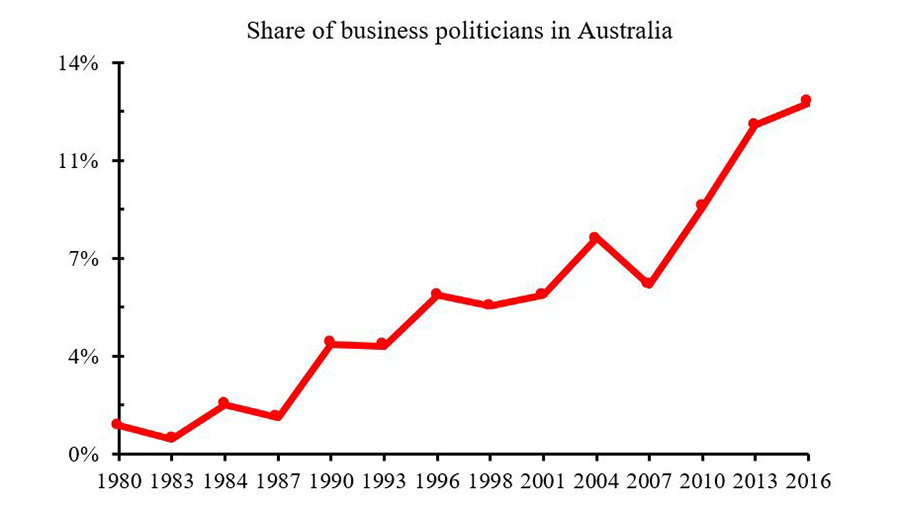

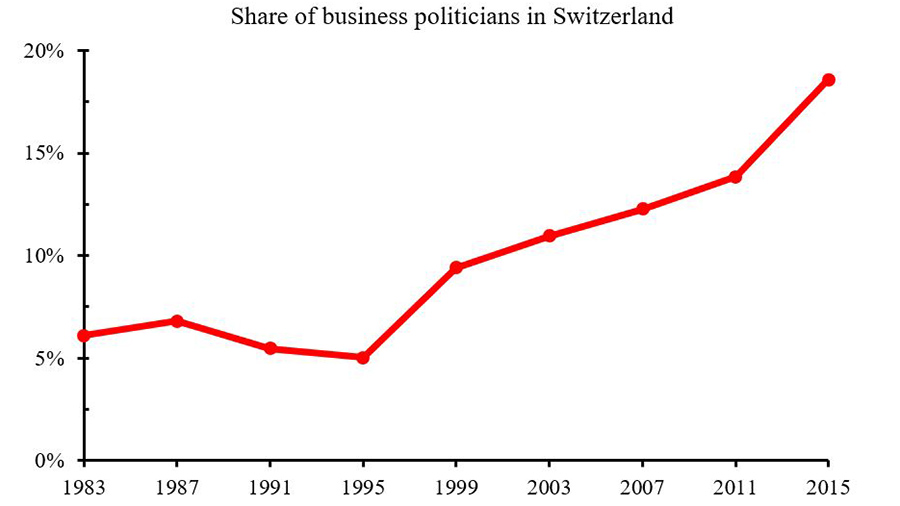

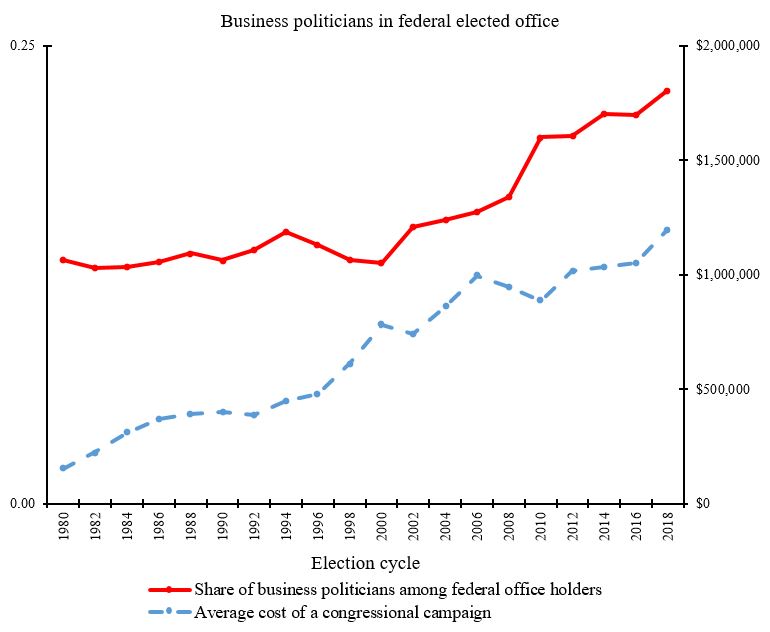

In Figure 1, we plot the share of politicians who, prior to being elected to national office (such as the British Parliament), had been senior corporate executives such as CEOs or Chairpersons. While the exact pattern varies from country to country, the share of business politicians in each of the four countries we examine is invariably higher today than at any other point during the last forty years. This is also true for the United States, where the share of business politicians in federal elected office increased from 13.3 percent in 1980 to 22.6 percent in 2018, with most of the increase occurring over the last two decades (see Figure 2).

One factor that may have contributed to the increase in the number of business politicians is the rising cost of political campaigns. When campaigns are expensive, candidates who can either self-fund themselves or have access to a network of wealthy donors are likely to enjoy an electoral advantage. Indeed, Figure 2 shows that, at least in the United States, the increase in the share of business politicians has been accompanied by an increase in campaign expenditures.

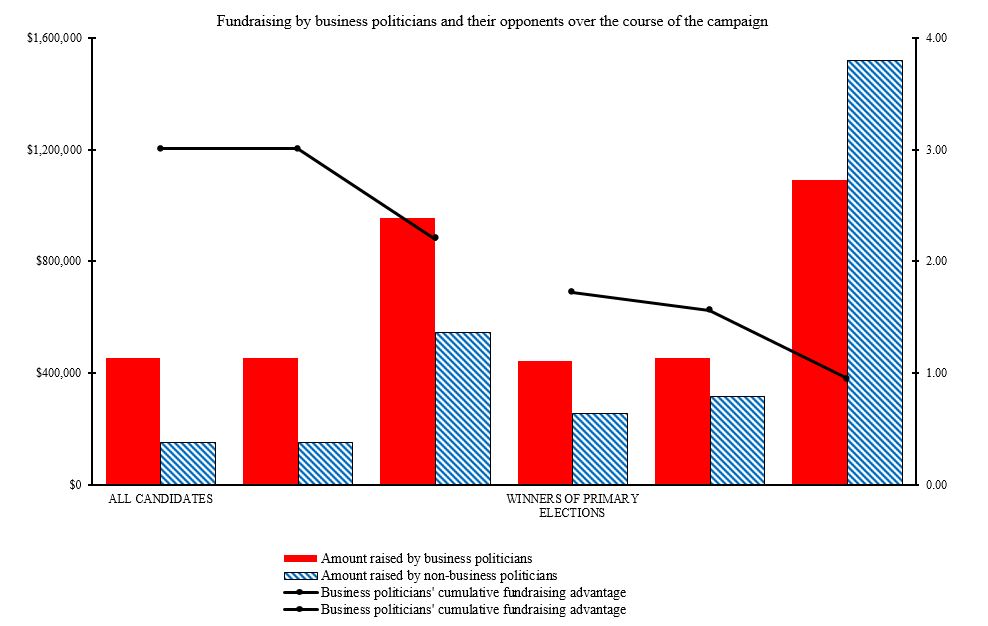

While we cannot establish a causal link between campaign finance and the rise of executives in politics, there are several pieces of evidence suggesting that business politicians have a fundraising advantage over their opponents. First, business politicians are more likely to self-fund their campaigns. Twenty-four percent of business politicians contribute at least $1 million of their personal funds to their campaigns, compared to four percent of non-business politicians. Second, business politicians outraise their opponents early on in the campaign, which prior research suggests is important for electoral success. Notably, some of the fundraising advantage of business politicians comes from their firms, which donate six times more money to their executives running for office than to other political candidates.

Figure 3 demonstrates graphically that business politicians’ fundraising advantage is substantial and that it is particularly large during the early stages of the campaign. To construct the figure, we first compute the duration of each electoral campaign as the number of days between the filing date on the Statement of Candidacy and the election day. Based on this duration, we split each campaign into three equal time intervals (or stages): the beginning, middle, and end of campaign. For each stage of the campaign, we first collect contributions from PACs and individuals received by business politicians and their opponents. We then compute business politicians’ cumulative fundraising advantage at each stage of the campaign by calculating the ratio of business politicians’ cumulative campaign contributions to their opponents’ cumulative campaign contributions.

In the full sample of all candidates, business politicians raise three times more money than their opponents early in the campaign (left panel of Figure 3), suggesting that they are in a better position, relative to their non-business peers, to bear the increase in campaign costs.

Why does the increase in the number of business politicians matter? One reason is that business politicians are likely to enact laws favorable to business even if the voters who elect these politicians may not necessarily welcome pro-business legislation. Evidence gathered by John Matsusaka, for example, shows that legislators often vote their own preferences even when their personal views diverge from the majority of their constituents. By using close elections for identification, our paper shows that business politicians indeed shift the balance of power toward corporate interests over and above what would be expected had they simply followed the preferences of their constituencies.

On the balance, there has been a marked increase in the number of corporate executives seeking political office, and this increase appears to have shifted the balance of power toward corporate interests.

Authors would like to thank Tingquan Pan as well as Imran Cader and Tilman Kemper for help with collecting some of the data used in this article.