The early history of the Sherman Antitrust Act offers relevant insights to contemporary debates on how to best enforce antitrust laws. In fact, the current controversies regarding the adequacy of US antitrust laws echo the debates surrounding the enforcement of the Sherman Act in the first decade following its enactment in 1890.

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

Antitrust enforcement appears to be a significant priority of the Biden administration. Many of the personnel decisions announced so far, such as Lina Khan as the Chair of the FTC, Tim Wu as a member of the National Economic Council, and Vanita Gupta as Associate Attorney General have brought advocates for new and more aggressive approaches to antitrust into positions of power. An executive order signed by President Biden this month launched a number of new initiatives related to competition policy as well.

But whether or not any change in the approach to the enforcement of antitrust laws will actually be effective is another matter. The FTC recently suffered a major setback in its suit against Facebook, as the judge held that it had failed to establish that the social networking company actually possesses market power. Advocates for more aggressive approaches to regulating dominant technology companies responded by arguing that the ruling proved that existing antitrust laws are inadequate and need to be changed in order to effectively police Big Tech. Others have instead claimed that the challenges posed by technology platforms would be best addressed by creating a new regulator focused entirely on those firms—like an FDA or FCC or FAA, but for the technology platforms.

The early history of federal antitrust laws offers some insights that are relevant to these debates. Although today’s dominant technology companies pose significant challenges for antitrust enforcement, those challenges are not without historical precedent. In fact, the current controversies regarding the adequacy of our antitrust laws echo the debates surrounding the enforcement of the Sherman Act in the first decade following its enactment in 1890.

In the late 1890s, the largest merger wave in American history occurred, as thousands of manufacturing companies were combined into large industrial “trusts.” Following the federal government’s defeat in a case against the Sugar Trust in 1895, the Sherman Act came to be regarded by some federal authorities as useless for restraining horizontal combinations. Yet this pessimism proved unwarranted: renewed efforts to enforce the Sherman Act pursued by President Theodore Roosevelt when he came into office proved to be much more successful, and rehabilitated the statute as a tool for policing anticompetitive behavior by the dominant firms of the era.

“Although today’s dominant technology companies pose significant challenges for antitrust enforcement, those challenges are not without historical precedent.”

The Sherman Act was passed into law amid fears that trusts and cartels, particularly among railroads, exerted a dangerous degree of economic power. In its first decade, the federal government won some significant victories in cases against railroad cartels. Yet its suit against the American Sugar Refining Company, commonly known as the Sugar Trust, ended in a defeat with far-reaching implications. In its decision in United States vs. E.C. Knight Company in 1895, the Supreme Court held that the merger of sugar refiners into a single firm that controlled 98 percent of the industry’s capacity did not fall within the jurisdiction of the Sherman Act.

Consistent with the constitution’s commerce clause, the Sherman Act prohibits efforts to monopolize interstate “trade or commerce.” The court’s reasoning in its decision was that the merger of competing sugar refiners, all of which were located in the State of Pennsylvania, into a single entity that controlled the manufacturing capacity of an entire industry did not violate the Sherman Act, since manufacturing itself was not interstate commerce. The decision was commonly interpreted as holding that the Sherman Act did not apply to manufacturing companies. Since manufacturers were prohibited from forming cartels to restrain competition, the strategy that they had typically followed throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the E.C. Knight decision seemed to give them free rein to merge instead. And, indeed, they did.

During the “Great Merger Wave” of 1895-1905, scores of competing manufacturing corporations merged to form industrial trusts that often dominated their industries. In just one decade, the structure of industrial production across many sectors of the economy was radically changed. Amid outcries that the new combinations held monopoly power and needed to be restrained, the federal government did not attempt to apply the Sherman Act to those trusts. The Attorney General claimed that the jurisdictional problems that arose in the Knight case were so significant that any effort to apply the Sherman Act to manufacturing corporations would inevitably result in “humiliating defeat,” and refused to try.

Yet even at the time of the E.C. Knight decision, some voices argued that the government could have pursued a different strategy to more successfully apply the Sherman Act to that company, and to manufacturing companies more generally. The case made against E.C. Knight had focused on the share of the industry’s manufacturing capacity held by the firm, and failed to document any commercial implications of the trust’s dominant position, such as the manipulation of input or output markets. New cases that focused on the behavior of horizontal mergers and their impacts on national markets might have met with success.

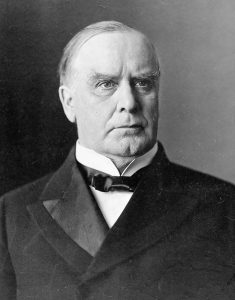

The Assassination of President McKinley and the Sherman Act

The failure to attempt to apply the Sherman Act to the industrial trusts in the years after 1895 is best understood as a political decision, rather than a consequence of the Knight precedent. The president at that time was William McKinley, who had defeated the populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the Presidential Election of 1896 with the aid of enormous sums raised from financiers and industrialists. McKinley’s policy agenda was generally favorable to big business, and his administration likely found the Knight decision a convenient rationale for inaction in the face of a merger wave led by some of their largest donors.

A sudden change in political leadership then demonstrated the possibilities for the enforcement of the Sherman Act that remained open. In 1901, President McKinley was assassinated and succeeded by his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt shared McKinley’s support for the gold standard and for most other elements of the Republican Party’s agenda, but he was much more interested in restraining corporate combinations. As president, Roosevelt cautiously selected new antitrust cases, being careful to avoid the jurisdictional problem raised in the Knight decision, and used the precedents established in some early victories to gradually purse an ambitious enforcement agenda.

Early in 1902, Roosevelt’s attorney general, Philander Knox, filed suit against a 1901 merger of the largest competing railroads operating in the northwest, which was known as the Northern Securities Company. Knox initially expressed skepticism about prosecuting the combination, but Roosevelt insisted they find a way. The Northern Securities Company was a holding company formed to consolidate control over competing railroads, and as in the E.C. Knight case, the defendants argued that the combination had no direct effect on interstate commerce. Yet the government argued that the purpose of the combination was to restrain trade, and cited earlier supreme court decisions holding that railroads were engaged in interstate commerce. Ultimately the federal government’s suit was successful, and its victory in the case in 1904 established an important precedent against mergers of competitors. It also contributed to the end of the wave of mergers that had begun in 1895 and continued to that year.

Roosevelt used the Sherman Act much more aggressively than his predecessors, initiating three times as many suits as the previous three presidents combined. The precedent established in the Northern Securities case was used by Roosevelt’s attorneys general in suits against some large and economically important trusts such as Standard Oil, American Tobacco, and Du Pont. The Standard Oil case in fact relied on many of the same tactics and arguments that had been successful in Northern Securities, although it also included evidence of the predatory and abusive tactics employed by Standard Oil in establishing and maintaining its monopoly. Those three cases were also successful, and resulted in the break-up of the first two, and the divestiture of the third of some recently acquired competitors. Perhaps more importantly, the precedents established in those cases influenced antitrust enforcement for some time.

Roosevelt’s presidency shows that the executive’s discretion over the approach taken to enforcing antitrust law can be quite important. His accession represents an unusual transition in which there was no change in the law, no change in the composition of Congress (and therefore in the prospect of immediate changes in the law), and in fact no changes in senior personnel in the executive branch. Even his attorney general, who was charged with enforcing antitrust statues at that time, had been appointed by McKinley. All that changed was that a new policy agenda was introduced, through the sudden and unforeseen transition from McKinley to Roosevelt.

“The lesson of Roosevelt’s presidency is that an aggressive and creative strategy to work around the limitations imposed by judicial precedents can have an impact.”

In a recent paper, we use the stock market’s reaction to Roosevelt’s sudden accession to the presidency to study the expected impact of the transition, and find that it was quite significant.

On the day that Wall Street learned that McKinley had been shot, the stock market fell by more than six percent, and the corporations that were the product of mergers following the 1895 Knight decision saw their valuations decline much more than others. The assassination was carried out by an anarchist terrorist, and one might be concerned that these stock market effects might have been the product of fears of the consequences of political instability, rather than the policy agenda of the new president. But McKinley did not die immediately. On the following day, his doctors pronounced that he would fully recover. The market responded by rallying, with the recent mergers enjoying differential gains. It was only seven days later that McKinley finally succumbed to an infection caused by his wounds. The announcement of his turn for the worse sent the market tumbling, and once again the recent mergers saw greater losses than other firms on average. Since the shooting of the president was already known, the announcement of his impending death several days later signaled only that a new administration would take power, and the market’s decline on that day was a response to the policy changes that were expected.

We also study the market’s response to the announcement of the Northern Securities suit. Roosevelt and Knox kept their efforts to pursue the case secret, so the government’s announcement of an impending suit was unexpected by the stock market, and conveyed clear information about Roosevelt’s antitrust agenda. Once again, the recent mergers saw their valuations decline differentially. Our findings suggest that the shift in the approach taken to antitrust enforcement had substantial effects for firms more likely to be affected by these efforts.

That prices fell in response to the news of Roosevelt becoming president, and in response to the announcement of his first antitrust suit, is evidence that McKinley’s neglect of the Sherman Act was a deliberate choice that benefitted incumbent firms. Although the Knight precedent created problems for applying the act to industrial trusts, it did not foreclose the possibility of doing so, and Wall Street clearly recognized the potential for a reformer like Roosevelt to use it in ways that threatened the profitability of those firms. The differential declines experienced by the recent mergers confirms that those firms were particularly vulnerable to stricter antitrust enforcement.

The Lesson of Roosevelt’s Presidency

Over the 120-year period since Roosevelt took office, antitrust enforcement has waxed and waned as a policy priority. It has at times been pursued quite aggressively, as when President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Thurman Arnold as Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust. Since the 1980s, it seems to have receded. No administration has neglected the Sherman Act to the degree that McKinley’s did, but there has generally been a lot of continuity in the tenor of antitrust enforcement in recent decades under both Democratic and Republican presidents. It has been quite technocratic in its approach, and challenges of mergers have been rare.

The lesson of Roosevelt’s presidency is that an aggressive and creative strategy to work around the limitations imposed by judicial precedents can have an impact. Roosevelt carefully selected early cases, and pushed Congress to pass the Expediting Act in 1903 to accelerate their progress to the supreme court. Although today’s dominant technology companies may pose unique challenges to antitrust enforcement, it may in fact be the case that the strategies employed so far in the federal government’s cases against them have not been particularly compelling, and that a different and more aggressive approach may be more successful.