Baseball’s antitrust exemption, currently the subject of fierce political backlash, has long been a historical curiosity. Why has a professional sports league enjoyed a legal monopoly for nearly a century?

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

Baseball’s antitrust exemption—which recently became the latest flashpoint in America’s culture wars—has long proven a headache for scholars who seek to explain its existence.

The exemption’s place at the intersection of two specialized fields, sports history and antitrust law, has long hampered efforts to understand it. Sports historians, whose expertise lies in on-field rather than courtroom drama, are often baffled by it. Legal scholars approach its relevant cases abstractly, logically, and out of context, and find themselves similarly confused. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, for one, expressed his bemusement at the exemption’s ability to “survive indefinitely even when surrounded by a sea of contrary law.”

Combining the historical and legal perspectives gives us a novel picture of how and why MLB’s legal monopoly came to be. The major leagues, conscious that the exemption stood on shaky legal grounds, leveraged their cultural influence to sway judges and politicians alike in their favor. They portrayed baseball as essential to America, and the exemption as essential to baseball. The exemption became an existential matter. To challenge it was to oppose the sport, and, by extension, the country itself—and very few dared to go that far.

Federal Baseball: The Beginning of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption

Baseball’s antitrust exemption began with a 1922 Supreme Court case, Federal Baseball v. National League. A few years earlier, a group of entrepreneurs had set up the Federal League to compete with the National League, then the sport’s preeminent institution (and one of MLB’s constituent parts). Federal League clubs aggressively poached National League players, enticing them to jump ship with larger contracts and friendlier labor policies. In retaliation, National League owners bought and shut down every rival team, save for one. Baltimore, that last club standing, sued.

At first glance, Federal Baseball seemed like a straightforward case—the National League itself did not deny that its behavior was monopolistic. The Court, however, ruled that baseball was exempt from antitrust law because it was not “interstate commerce.” Successive generations of legal experts have puzzled over this decision. Baseball seemed to clearly be interstate commerce; as the plaintiffs had argued, “the continuous interstate activity of each [team] is essential to all the others.” Beyond that, the very next term, the Court declared that traveling vaudeville shows, which followed a similar business model, were a form of interstate commerce.

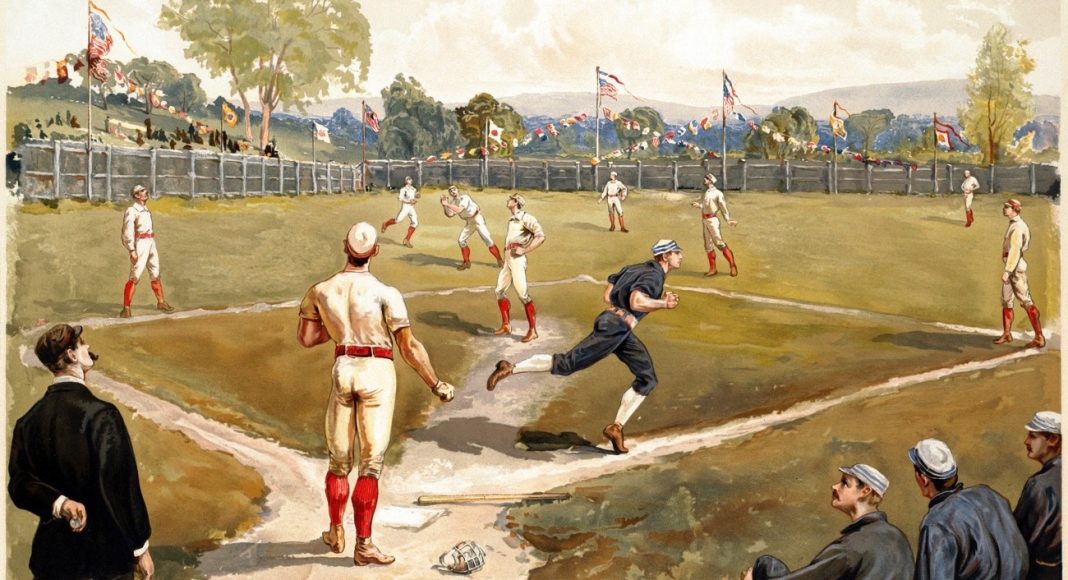

From a strictly legal standpoint, Federal Baseball makes little sense. Seen through a different lens, though, it appears to be the logical conclusion of several cultural trends that had been brewing for decades. These trends date all the way back to baseball’s early years, in the latter half of the nineteenth century. At that time, most Americans knew baseball as an amateur game, unrecognizable from the standardized, professionalized sport it later became. Rules varied, sometimes dramatically, from town to town. Any makeshift surface—an empty lot, an alleyway—could serve as a field. Bases were made of rocks, bats from sticks, and balls from materials as diverse as thread, buckshot, or shoe soles. Above all, baseball was a local, physical activity, not a spectator sport.

The Justices that decided Federal Baseball were all born between 1841 and 1862. Their generation was obsessed with the sport (one obituary to Justice William Day simply read: “Justice Day had one hobby. It was baseball.”) and believed that its amateur roots were more than fundamental to it. As historian Harold Seymour wrote, they “were admirably suited to a young, essentially rural America”—they encapsulated the country’s pastoral, democratic genius. It just so happened that in 1922, both baseball’s amateur ideal and the way of life it represented were under attack.

Driven by the efforts of businessmen who spotted baseball’s potential for mass entertainment, the sport was rapidly becoming more commercial and professional. In the eyes of many, the introduction of money into baseball turned it into a shady pastime, rife with cheating, gambling, and hooliganism. This perception peaked in 1919, when a group of bookies rigged the World Series in what Seymour dubbed “baseball’s darkest hour.” At the same time, America was transitioning from a largely rural, agrarian society into an urban and industrial one, a shift that many saw as the cause of widespread corruption, inhumane conditions, and moral decline.

These changes were best expressed by F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was not only a great chronicler of the era, but also a rabid sports fan. The Great Gatsby opposes the characters of Meyer Wolfsheim, the caricatured Jew who “fixed the World’s Series,” and Tom Buchanan, the New England aristocrat who starred in Yale’s football team. As an unpaid college athlete, Buchanan embodied the fading ideals of both amateur sports and pastoral America; as a crooked, urban immigrant, Wolfsheim represented the specter of industrial modernity.

“In the eyes of many, the introduction of money into baseball turned it into a shady pastime, rife with cheating, gambling, and hooliganism.”

Against this stark backdrop, the National League presented itself as an institution capable of upholding baseball’s amateur ideals and healing a country in crisis. In the wake of its 1919 scandal, it rebranded itself as a virtuous league. It cracked down on gambling in a highly-publicized campaign, forbade alcohol sales in stadiums, banned Sunday games, and raised gate prices to drive out unsavory, working-class fans. By casting itself as the heir to baseball’s history, it painted its rivals as hotbeds of immorality.

Through efforts like these, the National League drew associations with America’s pre-industrial values. In claiming to preserve baseball’s amateur ethos, the League portrayed itself as a vehicle for promoting public health, preserving nature (in the form of the field), and carrying traditional values into the modern, urban age. The League’s arguments relied on two rhetorical conceits that endure to this day: the idea that professional sports are ‘just games,’ no matter how much money is poured into them, and the idea that watching sports somehow makes viewers more athletic. While it is easy to feel jaded about those tropes now, they proved powerful in 1922, when their audience had grown up only knowing amateur sports.

To make its case, the National League leaned heavily on sports writing, a genre which was known for its lack of objectivity. Most sportswriters entered the business because they themselves were fans. At the time, a portion of their salaries was paid by the teams they covered, rather than publishers. Both their access to breaking stories and their employment were contingent on pushing the League’s desired stories. The coverage of the time reflected that bias. Newspapers routinely argued that regulation would doom the sport; the plaintiffs were dubbed “outlaws” and accused of conducting “raids.” Headlines like New “Outlaws” Threaten Peace of Big Leagues, as well as columns declaring that antitrust law “threatene[d] the entire fabric of… baseball,” were commonplace.

Capitalizing on the cultural concerns of the twenties, the National League linked the usually dry topic of antitrust regulation to its own survival, nostalgia for amateur baseball, anxiety over industrialization, and what it meant to be American. In the absence of countervailing media narratives, the League’s arguments imposed themselves as general truths. Their influence on judges’ mindsets emerged in their opinions, which are notable for their refusal to accept that baseball could be a business.

“Capitalizing on the cultural concerns of the twenties, the National League linked the usually dry topic of antitrust regulation to its own survival, nostalgia for amateur baseball, anxiety over industrialization, and what it meant to be American.”

The Federal Baseball Court upheld a previous judgement by the DC Court of Appeals, which had claimed that “baseball was not ‘trade or commerce,’ but ‘sport.’” Several related lower-court rulings echoed this reasoning; in one, Judge Kenesaw Landis (who went on to serve as baseball’s commissioner) wrote that “as a result of thirty years of observation, I am shocked because you call playing baseball labor.” Landis’ case is particularly instructive: His lengthy experience with the sport made him susceptible to the League’s argument—he still saw playing baseball as an amateur pastime, so it was impossible for him to conceive that it had become a salaried profession like any other.

For judges like him, recognizing that baseball was interstate commerce meant accepting that it had become a business. To do so, especially in the intellectual climate fostered by the League, was tantamount to giving up on baseball’s ideals and America’s traditions—and that was a step too far for the judges. Instead, they ended the case there, and hoped that the newly monopolistic major leagues could return baseball to its good old days. They did not.

The Fifties

By 1950, the major leagues had completed baseball’s transformation into mass entertainment and big business. The amateur ideal was all but forgotten; in fact, professional baseball easily replaced it as a symbol of modern America. Its games, stars, and stories, broadcast to all, became elements of a shared culture that united a sprawling country. Even its new mythos—as a meritocracy where any talented player could thrive, regardless of his background—seemed tailor-made for the age of the American Dream and the Cold War.

Ironically, the exemption helped the leagues accomplish this transition. It allowed them to subsume competitors into their “farm system” and negotiate monopolistic media deals to buttress their radio and television empires. More importantly, it enabled them to conduct a controversial practice, the reserve clause.

According to this contractual kink, when a player signed his first contract with a team, that team “reserved” his “rights” forever. Even after his contract expired, he was forbidden from negotiating with other teams; he could only switch clubs by being traded or released. Teams used the clause to form a cartel. They offered players one-year deals at rates far below what they would command on an open market, and they enforced the clause by banning noncooperative players from the entire professional baseball network.

The antitrust exemption came under fire several times in the fifties, partly because the reserve clause was so blatantly anticompetitive, and partly because professional baseball had grown so much that it had clearly become interstate commerce. Several players threatened to sue the leagues over the reserve clause (and three of them did, in Gardella v. Chandler, Kowalski v. Chandler, and Toolson v. Yankees); Congress also repeatedly brought up the prospect of antitrust legislation targeting baseball. The major leagues responded to each antitrust challenge by adapting their earlier playbook to their new cultural context. The shape of their argument—that the exemption was key to baseball, and that baseball was key to America—remained the same. Its content, however, proved very different: it played on the anticommunist, pro-business fervor of its time.

These tendencies were first put on display in the 1949 case Gardella v. Chandler. Danny Gardella, a player, had previously broken the reserve clause by signing a lucrative contract with the Mexican League, which had recently been taken over by a pair of wealthy businessmen. When Gardella sought to return to the United States, Albert Chandler, baseball’s commissioner, blacklisted him. Gardella quickly sued. The case’s international dimension was telling—baseball’s domestic monopoly was so secure that its only competition came from abroad.

This cross-border element also offered the leagues a prime opportunity to display their new patriotic rhetoric. For one baseball executive, Gardella and his lawyers were men “of avowed communist tendencies”; for commissioner Chandler himself, they were “disloyal” to both sport and country. To challenge the reserve clause was to challenge baseball, to challenge baseball was to be anti-American, and to be anti-American was to be a communist. In the end, the leagues’ campaign forced Gardella into settling, and the exemption lived to see another day.

A couple of years later, in 1951, the House Judiciary Committee opened an investigation into the baseball monopoly and the reserve clause. The leagues’ response, articulated over several days of testimony, followed the pattern established in Gardella.

Their argument began by emphasizing the links between baseball as a spectator sport and American identity. Ford Frick, the sport’s new commissioner, described players as “idols,” “titans,” and “divine” before jumping into a list of saccharine baseball tropes (“hot dogs and peanuts,” for example) and calling the leagues’ critics Marxists. Then, the leagues’ representatives went on to claim that baseball could not exist without the reserve clause. Not only was it, in their words, economically “necessary” and “fundamental,” but it was also the source of “sportsmanship” and “fair play,” something “as important to baseball as balls and bats.” The hearings turned the reserve clause from a contractual bullet point into a pillar of baseball and Americana.

The leagues’ testimony was striking for its inversion of the rhetoric that dominated Federal Baseball. In 1922, the National League did everything it could to separate sport from business. In 1951, the leagues happily argued that sport was contingent on a business dealing—the reserve clause. Their testimony was also notable for painting the inherently anticompetitive clause as a free-market development. Philip Wrigley, the chewing-gum magnate and owner of the Cubs, said that it “just sort of grew” and “balances within itself”; Ed Johnson, a pro-baseball Senator, that it was “a natural arrangement” that had “grown slowly like a great oak.” Only in the McCarthyite fever of the time could such a paradox go unnoticed.

The leagues’ defense was a tremendous success. The ensuing House report parroted the leagues’ points, whether about Americana (“baseball is America’s national pastime”), the clause (“baseball could not operate successfully and profitably without some form of a reserve clause”), or the exemption in general (“baseball is a unique industry”). Congress made no effort to independently verify the leagues’ points. Representative Emanuel Celler, who chaired the investigation, later wrote that the pressure he faced from sportswriters and fans convinced him to take no further action—like Gardella, he was forced to settle.

“It is fitting that players led the most successful charge against the antitrust exemption. Only they, who experienced professional baseball from the inside, were in a position to doubt the leagues’ arguments.”

The Most Successful Charge Against the Antitrust Exemption Originated from the Players

After the House investigation closed, two players, George Toolson and Curt Flood, went back to the Supreme Court. Not only did the Court rule against them in opinions that echoed the leagues’ narrative, but it even strengthened the exemption’s legal basis. Even though the baseball was interstate commerce, wrote the Court, it could retain its exemption as an “exception” granted to meet the sport’s “unique characteristics and needs.”

The players finally decided they could rely on neither Congress nor the courts. Taking advantage of a new dispute resolution process they had won through collective bargaining, the players took the reserve clause to arbitration, where it was struck down. So, while baseball’s antitrust exemption endures to this day, its reserve clause was abolished in 1975—and, it must be said, none of the leagues’ doomsday scenarios ensued.

It is fitting that players led the most successful charge against the antitrust exemption. Only they, who experienced professional baseball from the inside, were in a position to doubt the leagues’ arguments. After all, the story of the exemption is one in which an influential institution harnessed its cultural power to sway the public, the judiciary, and the legislative into granting it special treatment.