A whole century has passed since Sadie Alexander became the first African American to receive a PhD in economics in the United States. Economist Nina Banks, editor of Democracy, Race, and Justice: The Speeches and Writings of Sadie T. M. Alexander, speaks with ProMarket about Alexander’s legacy and why it’s still relevant today.

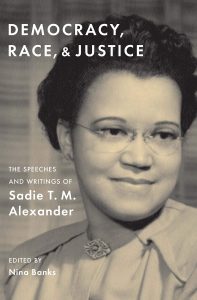

A hundred years ago this month, Sadie Tanner Mossell, Georgiana Simpson, and Eva Beatrice Dykes were the first three African American women to receive a PhD in the United States. Sadie Tanner Mossell, later known as Sadie Alexander, was the first African American to receive a PhD in economics. Unable to secure a job in economics, Alexander went on to become a lawyer. A new collection of her speeches and writings, Democracy, Race, and Justice: The Speeches and Writings of Sadie T. M. Alexander, reveals that even though Alexander was not employed as an economist, she used her training to push for equal rights and equal opportunities for African American workers.

“Racial discrimination undermined Alexander’s life as well as the collective memory of her work and breadth of economic thought,” Nina Banks, associate professor of economics and an affiliated faculty member in Women’s and Gender Studies and in Africana Studies at Bucknell University and the current president of the National Economic Association, wrote in a recent Washington Post piece. “But the speeches that she left behind attest to her brilliance and the relevance of her prescient observations to our current political economy. Indeed, she identified economic deprivation as the major obstacle for political, racial and economic equality, all of which remain elusive today. Her solution—full employment job guarantees—may be what we need to finally address persistent job discrimination, involuntary unemployment, inadequate wages and the racial disparities these injustices exacerbate.”

Banks spent years researching and restoring Alexander’s work. The book, edited by Banks, documents Alexander’s speeches throughout World War I and the Great Migration, the Great Depression, World War II and the postwar era, and the Civil Rights era of racial unrest. In an interview with ProMarket, Banks discussed Alexander’s work, including full employment job guarantees, and why it is still relevant today.

[The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.]

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

This book was a long time coming. Back in 2003, when I started researching Sadie Alexander, I went to the University of Pennsylvania archives in search of whether or not Sadie Alexander had continued to think about economic issues, because in those days, economists assumed that after she became a lawyer, she had given up her interest in economics. I was motivated by the work of other feminist economists, and especially the work of Julianne Malveaux, who had published an article in 1991 in the American Economic Review, “Missed Opportunity,” which looked at her thoughts on the absence of Sadie Alexander’s thinking on the economics profession.

When I went to the archives, and I was reading through this huge amount of materials, over 81 boxes, what I realized very early on is that Sadie Alexander had always thought about economic issues and had spent her life focusing on the economic concerns of African Americans. I received permission from the University of Pennsylvania in 2005, to write an edited volume of her speeches, because I realized that really a common theme of her work in economics was economic justice. Since 2005, I’ve been in possession of these speeches, but there have been a lot of challenges in trying to disseminate the research and to do the research. But her focus on economic justice was always the motivation, and then to really restore her economic thought to the discipline of economics—that was a goal early on as well, which has finally been realized with the publication of this book.

Q: In your acknowledgments, you write that you met with young economists at Oberlin: “They shaped my thinking on Sadie Alexander and economics as well as the many ways in which mis-education sometimes serves as a catalyst for critical thought and action as it did for Alexander.” I wondered if you could elaborate on that in terms of how it shaped your thinking, and also on how today’s young women—Black women economists—play into why this work is so important.

In 2014, a group of undergraduates at Oberlin contacted me about giving a talk to them on Sadie Alexander. That was the first invitation I had received. I was really struck because they were a part of a women in economics group and a rethinking economics group. What they said is that they felt that their education was not sufficient, because it wasn’t grounded in social justice, economic justice. They had read the article that I did, I think, on Sadie Alexander’s thoughts on the black worker and economic justice. And so they wanted to hear more about that.

Sadie Alexander had an interdisciplinary education. She was influenced by training in history, historical analysis, and sociology, in addition to economics. But she was also mis-educated at the University of Pennsylvania when it came to African Americans and African American history. She faced a lot of hostility. She had a sociology class that disseminated this view of African Americans being inferior. And so I thought about Sadie Alexander’s mis-education and the role that it played in her attempts to really dispel this notion of African American inferiority. All of her early speeches were about the contributions of African Americans to our nation. And the Oberlin students who thought that they were being mis-educated in their economic classes, because they didn’t have sufficient grounding in economics that focused on theories of social justice. That was the parallel there.

I don’t focus on just Black women when it comes to Sadie Alexander, because Sadie Alexander didn’t develop an economics that was focused on Black women in particular. There’s this notion out there that Sadie Alexander emphasized Black women and she did not. When she talked about Black women in particular, it was about Black women as a political force, and Black women’s leadership, potential, and skills as leaders. But when it came to the economy, Sadie Alexander focused on both African American men and women, probably more African American men even than women if I think about some of the issues that she was talking about over her lifetime in terms of the labor market.

Why that is a really important point for me to emphasize that she didn’t focus on Black women in particular, is that the early women economist were pigeon-holed, and stereotyped into this narrow box of women’s issues. And when I read people saying that Sadie Alexander emphasize Black women, to me, that is a form of discrimination that the early women economist experienced. So I’m pushing back against that, because that is a form of discrimination against Sadie Alexander’s thinking, she was not narrow. She was, in fact very, very broad.

Her economics should be a source of inspiration to all economists and people who are interested in economic issues and economic policies, beyond Black women. I certainly would hope that Black women look up to her, and other women would look up to her, and other men would look up to her, but her focus was broader than Black women. I’m glad you asked me that question.

“We must provide the hope and the certainty of productive employment to everyone, and especially to Negro young people. The basic purpose of this comprehensive design, this total process, is the development of the deprived, the neglected—the discriminated against—the minority—to its full potential. This is necessary not only to meet the ends of social justice and morality, to fulfill the guarantees of our constitution and laws, but because in this era of automation, when tens of thousands of unskilled and semi-skilled jobs are being eliminated, it becomes an economic imperative which is basic to our very existence as a free society.” — Sadie T. M. Alexander, 1963

Q: Alexander’s work on the labor market and some of the topics that you touched upon in the collection of her writings and speeches, like the full employment jobs guarantee, continue to resonate. What do you think about how her ideas can be applicable today?

When I did the webinar the other day for the book launch, one of the things that I said is that it took me a long time to be able to bring this book to fruition. But I actually think this is the right time for it to be published, that her ideas will resonate today more so than they would have in 2010, or 2015, because we are thinking about a lot of the same issues that she thought about. Full employment job guarantees is certainly one of those, but we’re talking now about the role of racial oppression in our history and with the focus on critical race theory, and these attempts to outlaw it. Sadie Alexander always talked about blocked opportunities that were structural, as well as ideological and the need to incorporate African American History in American schools in the curriculum. So, that’s also very current.

My favorite speech is the speech “Coming Events Cast Their Shadow,” where she’s really concerned about the tendency for an electorate to put a fascist in office who says that he can solve all of their problems. That’s very current. I really think that this is actually the best time to publish it, because there are so many issues that she raised, which readers will really ponder.

Q: I’m glad you mentioned that essay, because it goes back to what you said earlier, that she wasn’t just writing about Black women or Black men. She was also writing about white workers and their fears and how that played into the forces and the dynamics of the labor market.

If you think about it, when she was an undergraduate and a graduate student, that period of time during World War One was so important in terms of our history. It’s the beginning of the great migration of African Americans from the South to the North. They moved to the North with all of these hopes of being able to be incorporated into the expanding industrial economy. And she writes about that in her dissertation. Only they find blocked opportunities in the North as well.

One of the other things that happens during that period and shapes her thinking, is racial violence, mob violence against African Americans, which is part of what they left in the South. Hoping to escape, they go to the North. And in 1918, there’s a surge of racial violence in Philadelphia, white mobs are attacking African Americans over issues of housing. And then, of course, the Red Summer of 1919. And even two weeks before she graduated, with her doctorate degree, the Tulsa massacre. So racial violence and the tendency for white Americans to engage in mob violence against African Americans that always shaped her thinking, especially during periods of an economic downturn. That influenced her thoughts about the role of government in the macro economy, because she was always mindful that white workers thought the Black workers were competing against them for what they perceived to be as their jobs.

Q: In one of the sections, you write: “What is striking about the New Deal policies that Sadie Alexander identified as racially neutral in language, yet they still had a detrimental impact on Black worker and their families by worsening racial disparities.” There are a lot of comparisons now about the US living through a historic moment, the New Deal, and President Joe Biden having an opportunity to be the next FDR. But as Sadie Alexander pointed out, while some policies might appear racially neutral, they can be detrimental to Black workers. Is there anything to learn from her work as we move forward and try to figure out this post-Covid economy?

Those policies seemingly were racially neutral, but we know that Southern white democrats really wanted to have policies that excluded Black workers from benefits because they wanted to maintain this labor force in the South that had few options. That was part of what was going on. I know that there’s an attempt to correct some of those exclusions now in terms of agricultural workers, who still face some exclusions, and certainly domestic workers who still face some exclusions. I think the takeaway is to be mindful of the impact of policies on racial ethnic groups. How does it affect people? In some countries, there’s an attempt to look at policies from a gender standpoint. And so we need to be mindful of those policies in the United States, in terms of their racial, ethnic effects. Do they create disparities, for example? And so the takeaway is that policies that are seemingly racially neutral, usually are not.

The other thing is that African Americans have a unique history in this country. Sadie Alexander always focused on African Americans. That was her priority. If white workers benefited and other workers benefited from the policies that she advocated, then that was great. And sometimes her strategies were to focus on universal benefits, because she wanted white workers to come on board, but her priority was always: What will benefit African Americans so that African Americans can finally be included fully as citizens in this country?

We need to also be mindful of the distinctive history of African Americans in terms of policies that have disadvantaged African Americans and finding policies to make amends for those disadvantages.The big issue there, for example, would be farmers. That’s one example: the policies that systematically disadvantaged African American farmers. To go back now to today and say that the [few] corrective policies that are being advanced that they disadvantage white workers, that they are a form of discrimination against white workers, overlooks a very long history of policies that systematically dispossessed African American farmers of their land.

“Sadie Alexander’s economics should be a source of inspiration to all economists and people who are interested in economic issues and economic policies, beyond Black women.”

Q: As I was reading the book, the debate about critical race theory was playing out in the news. We’re trying to have this conversation about mis-education of generations of Americans and about how to correct that. Where does Sadie Alexander play into it? If teachers are forbidden to talk about critical race theory, would they even be allowed to talk about the work that she had done, or some of the things that she was talking about? What are you thinking when you’re reading the news?

First of all, I’m thinking that teachers are not teaching critical race theory because most people don’t know what that is. The writings of critical race theory are taught in colleges at the undergraduate or especially at the graduate level. What the politicians are really saying is that they don’t want students in K-through-12 to be taught a curriculum that focuses on structural racial oppression. They want a curriculum that puts racism in the past, that [says] slavery was resolved after the Civil War and the civil rights movement, and that racism is the outcome of some bad individuals. That’s not very historical.

We know from reading Sadie Alexander’s speeches now that she’s talking about belief systems that are widely held, and she’s also talking about policies that were put into place, which disadvantaged African Americans. It’s structural, and it’s pervasive. What strikes me about all of that is that the people today who are talking about racial oppression are looking back and giving us this history. But the Alexander speeches, they were unfolding in real time. So even though we can read it as a history, the speeches were about what was taking place at that point in time. It’s very difficult then for people who are opposed to talking about the history of racism to argue against what somebody was saying at the time, who was observing these events unfolding.

Q: I used to cover the jobs report for The Guardian. And if you look at those numbers, the unemployment rate for Black Americans is still twice as high as that for white Americans. Anytime we would ask the experts commenting on the economic trends about it, they would say: “Well, it’s always been like that.” But doesn’t have to stay like that. So, it isn’t all in the past.

Exactly. It is not. And you’re right, that’s the key. It has been pervasive, and it does not have to stay that way. It should be unacceptable that African Americans have unemployment rates that are consistently twice as high as white unemployment rates, if we are in a recession, or even in a period of recovery, or expansion. That gap is unacceptable, because we should be thinking about the impact that it has on people and on their well-being.

One of the other areas where I think Sadie Alexander’s thinking will resonate with readers today is her idea about the importance of investing in public works programs, but not just physical infrastructure of roads, in buildings, but also the social infrastructure or what people are calling human infrastructure today. In 1945, she’s talking about this fully employed economy, job guarantees, and the way to do it is through investments in social infrastructure to combat these big areas of social needs, in terms of clearing up slums or providing access to basic utilities to all Americans. We can think about so many of those needs today as a way of providing full employment to all people who are willing and able to work, which is what she advocated for.