A new paper shows that platform mergers can harness network effects at the cost of reducing the platform differentiation that users value.

The societal importance of digital platforms is universally recognized, but the economic forces affecting the size of these platforms are still poorly understood. The typical explanation for why digital platforms are so large is that they harness network effects, which occur when the benefit to using a platform for one user increases with the number of other users on the platform. Yet, when looking at competition between digital platforms, we don’t always see users naturally shifting to a single platform, which a simple theory of network effects would predict. Instead, platforms often cement their market dominance by acquiring or merging with competitors, such as Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram.

Whether platform mergers are good for users is an empirical question, since theory does not have clear predictions about their effects. On the one hand, by pooling users onto a single platform, mergers may create more and better interactions among platform participants and a superior user experience. On the other hand, mergers may hurt users by eliminating competitors. This harm could materialize when a platform acquiring a competitor takes advantage of its new dominant position to increase prices, lower quality, or reduce innovation. If two competing platforms cater to different types of users in a way that a single combined platform cannot, an acquisition can also hurt consumers by reducing platform differentiation.

Measuring the economic consequences of platform mergers is difficult, since this requires obtaining data about the users of both platforms, before and after the merger. In our research, we are able to overcome this challenge by considering platforms for peer-to-peer dog-sitting services. These platforms facilitate matches between pet owners and pet sitters with an interface that handles search, communication, and payment between the two sides of the market. Rover is the platform leader in the US, and in 2017 it acquired and shut down its main competitor, DogVacay.

Three features of this merger make it well-suited for measuring how large network effects are and whether they can justify a monopoly over competition. First, the dog-sitting market is segmented by geography, so that users in a city mainly interact with each other and not with users in other cities. Second, the market shares of the two platforms differed across cities. In Seattle, for example, Rover was already the dominant platform even before the merger, while in other cities market shares were more evenly split. This variation allows us to consider markets like Seattle, which were already dominated by Rover, as a control group when studying the effects of the merger on markets that were more evenly split or where DogVacay was dominant. Third, Rover’s platform fees did not change immediately after the merger, meaning that at least in the short term, the dominant platform did not take advantage of its increased market power.

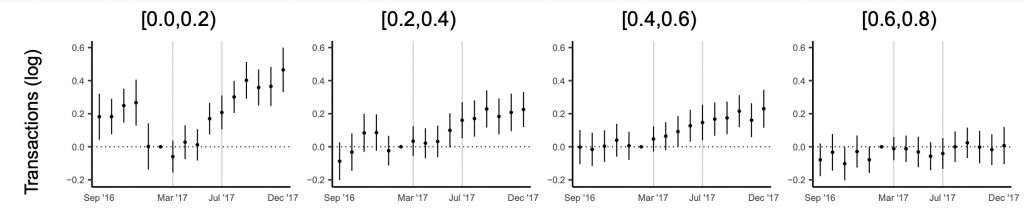

Our first result confirms the existence of sizable benefits from network effects. Rover’s platform design remains the same post-merger, with the exception of an influx of users from DogVacay. Therefore, we would expect that the bigger the influx of users from DogVacay, the bigger the benefits to users on Rover pre-merger. This would be true for both pet owners and sitters. Increasing owners and sitters at the same rate—i.e., holding constant their relative shares—could benefit both sides of the market by allowing more and better opportunities to match. Indeed, that’s what we find: users who were already on Rover before the merger were retained at higher levels and exchanged more transactions in markets where DogVacay was relatively bigger. The effects in Figure 1 show a 26 percent increase in transactions by Rover users in geographies where Rover had less than 20 percent market shares before the merger (first plot from the left), and around 17 percent increase in transactions in geographies where Rover had between 20 percent and 60 percent of the market (second and third plot from the left). This increase in transactions, which occurs for sitters as well, is consistent with sizable network effects benefits.

Figure 1: Transactions by pet owners on Rover. The first vertical line denotes the merger announcement, while the second vertical line indicates when DogVacay was shut down

In a naive model where network effects are the only mechanism changing user utility after the merger, we would expect the merger to improve outcomes the most in more evenly split geographies. This is because in geographies where both Rover and DogVacay had approximately 50 percent market share, the merger effectively doubles the number of people each user can interact with, while in geographies when one platform was already dominant the change in platform size is much smaller.

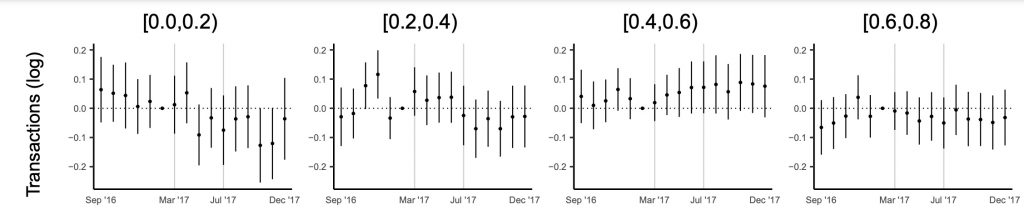

Figure 2 disproves the naive theory of network effects. The aggregate number of transactions in a geography remains relatively constant over time, relative to our control geographies. In particular, we find that on average, matching outcomes are not significantly different between a single dominant platform and two competitors.

Figure 2 tells us that other economic forces are present, which offset platform-level network effects of Figure 1. In particular, we find that DogVacay users, even though they also enjoy the benefits of a larger platform, are on average worse off because their preferred platform was shut down.

It seems puzzling that users had such strong preferences for transacting on DogVacay, given the close similarities between Rover and DogVacay. We argue that this preference is explained at least partly by the role of repeat transactions. If buyers have already found a suitable and reliable seller with whom they can transact offline, there is little reason for them to switch to a new platform

“we show that platform differentiation can be an important mechanism offsetting the network benefits of larger platforms, even in industries where platforms appear very similar.”

Our study has implications for merger evaluation beyond the pet-sitting market. Despite the existing emphasis on pricing power in antitrust policy, our results suggest that dominant platforms, especially if they are still in their growth phase, are unlikely to raise prices as a consequence of increased market power. Instead, we show that platform differentiation can be an important mechanism offsetting the network benefits of larger platforms, even in industries where platforms appear very similar.

To evaluate the costs of a reduction in platform differentiation, regulators need to understand whether users have heterogeneous preferences for different platforms. For example, regulators can measure whether users tend to use one or multiple platforms at the same time (multi-homing). Other data may be acquired from surveys eliciting the preferences and characteristics of platform users. These metrics may uncover whether platforms specialize in matching different types of users, a theoretical possibility highlighted by a 2018 paper by Hanna Halaburda, Mikołaj Jan Piskorski, and Pınar Yıldırım. If heterogeneous preferences are strong and platforms specialize in a particular user type, shutting down acquired competitors may be detrimental to users, even despite the sizable benefits of network effects.

There is still relatively little research that uses data to measure the benefits and costs of competition among digital platforms. We show that, at least for one industry, the role of network effects, pricing power, and platform differentiation balance out in the short run. In other industries, where the benefits from scale are not limited to cities but rather extend to global networks, network effects may be more likely to justify dominant platforms. On the other hand, in industries where heterogeneous preferences play a larger role, competition is likely to be optimal for users.