We are all victims of what George Stigler described as “the pervasive use of state support of special groups” and of governance failures everywhere. But we should not be helpless, writes Anat Admati.

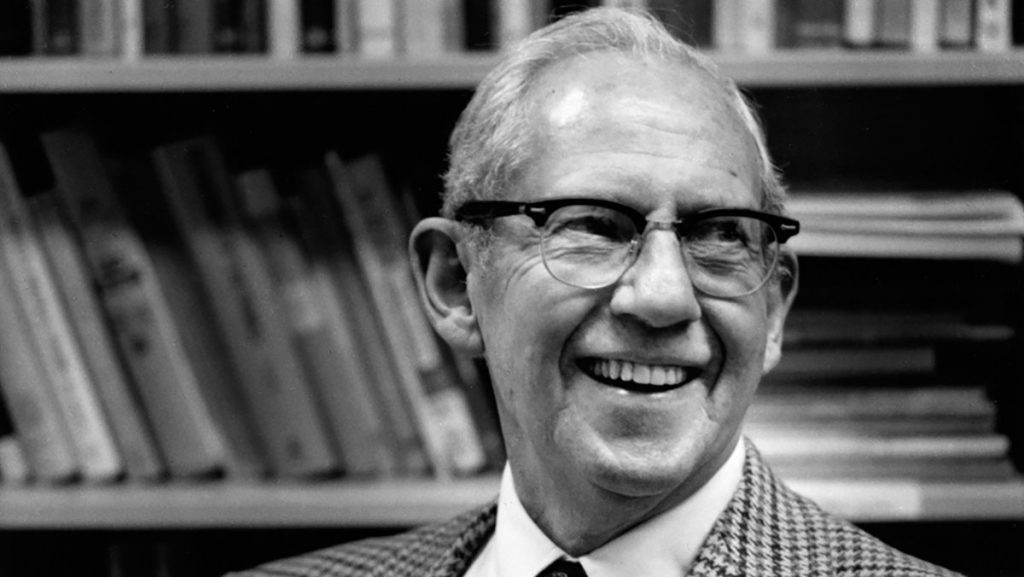

Editor’s note: In 1971, George Stigler published his article “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” To mark the 50-year anniversary of Stigler’s seminal piece, we are launching a series of articles examining his theory’s past, present, and future legacy.

This piece is also part of our series on Corporations and Democracy, designed to continue the conversation initiated at a December 2020 conference by the same name. See the conference’s website for a summary of the event, the program, full videos, and other links.

In his 1971 article on the theory of economic regulation, George Stigler noted insightfully that the engagement of corporations with governments affects economic outcomes, and that imbalances of power and expertise can distort democracy and harm society. “Until the basic logic of political life is developed,” Stigler lamented in the conclusion, “victims of the pervasive use of state support of special groups will be helpless to protect themselves.”

Stigler’s article appeared shortly after his colleague Milton Friedman published an impactful essay urging business managers to “make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of society” to fulfill their “social responsibility.” In his essay, Friedman accepted that government actions should be guided by democratic processes, but he ignored the possibility that managers who follow his dictum to increase profits may seek to distort these democratic processes, so that the “rules of society” benefit their special interest even against society’s interest. Stigler, on the other hand, asserted that such distortions happen “as a rule” in the context of regulations.

Whereas Friedman based his recommendations on a presumption that managers operate in “free and competitive markets without deception and fraud,” Stigler asserted that corporations often coerce governments to create regulations that prevent competition. In reality, corporations engage with governments at every level of policy. This engagement can have an impact throughout the often lengthy and complex processes of the writing and enforcement of laws, regulations, and trade agreements. In addition, governments often enter transactions with corporations to buy goods and services, which involves choosing providers and setting and enforcing the contract terms.

As Cass Sunstein argued, Stigler’s “thesis” and the notion of industries “acquiring” regulations are false if taken literally. Steven Vogel noted that corporations often lobby against regulation. Regulatory capture may actually lead to inadequate yet overly complex rules that create revolving job opportunities for those familiar with the details. Complexity can obscure the regulations’ poor design and ineffectiveness.

But Stigler also presented a more nuanced and balanced view of the process by which rules are set that applies beyond regulations to legislatures and other related contexts (e.g., the setting of accounting standards). Institutional decisions, in government and elsewhere, especially the setting of rules, are determined through political processes. According to Stigler, politics “is an imponderable, a constantly and unpredictably shifting mixture of forces of the most diverse nature, comprehending acts of great moral virtues (the emancipation of slaves) and of the most vulgar venality (the congressman feathering his own nest).” Political processes, in other words, are complex and messy and their outcomes may benefit society or instead reflect corruption and abuse of power.

In August 1971, shortly after the publication of Stigler’s article, Lewis Powell, a corporate lawyer later appointed to the Supreme Court, sent a memorandum to the Education Director of the US Chamber of Commerce that called for corporate America to become aggressive in molding society’s thinking about business, government, politics, and law. The memorandum inspired campaigns to insert anti-government and anti-regulation narratives into channels of intellectual and political influence. Ronald Reagan reflected such attitudes, famously saying in his 1981 inaugural address “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.”

Political battles involve people and groups trying to influence those with power to make important decisions. As Stigler recognized, these people and groups may have conflicting preferences and may also differ in their levels of resources and knowledge of the issues. These asymmetries can have significant effect on the outcome. In a 2014 study, for example, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page showed that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on US government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”

In The Business of America Is Lobbying, Lee Drutman described the growth in lobbying activities by corporations and trade organizations in recent decades. Alex Hertel Fernandez explored how business groups and wealthy activists have reshaped American policy through coordinated efforts state by state in State Capture and elsewhere. As Jane Mayer exposed in Dark Money, the influence of money on political outcomes is often invisible to the public. Conflicted “experts” can impact policy disproportionately when issues are not salient.

Economists and the Importance of Engagement

Economists often naively assume that “social planners” make decisions in the public interest. Stigler was right to debunk this Panglossian view of regulations. His call to economists to study political behavior highlights the blind spots to the importance of politics that Milton Friedman displayed in his 1970 essay and that continue to pervade mainstream economics and other areas in business schools and beyond.

The financial sector provides stark illustrations of how political processes can lead to persistent government failures to counter the distorted incentives within a powerful industry. In May 2009, shortly after the near implosion of the financial system and the extraordinary supports numerous institutions at the center of the “free market” system received from the government and central banks, Illinois Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) said that “banks are still the most powerful lobby on Capitol Hill and they frankly own the place.”

A memoir titled Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins by Jeff Connaughton, who spent 25 years in a variety of jobs in Washington, DC, including in government and as a lobbyist, explains how banks have come to “own” the US federal government, including regulatory agencies. In one scene in the book, former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker tells Delaware Senator Ted Kaufman that the threats bankers make about the consequences of regulations they dislike are “all bullshit.”

“Bad systems can persist when the issues are not salient to the public. Change requires that people in a position to challenge ‘the tyranny of the status quo’ speak up and help to create political will for change.”

Since getting involved in the policy debate on financial regulations after the 2007-2009 financial crisis, I have witnessed firsthand the political process by which policy gets distorted and I have encountered many false and misleading claims (the “bullshit” to which Mr. Volcker referred) that affect important policy. If powerful people choose to maintain or enact bad policies and refuse to engage on how to improve them, they may get away with it if not enough people understand the issues.

Realizing that regulatory reforms were overly complex and yet entirely inadequate, four of us academics posted a paper debunking some “fallacies, irrelevant facts and myths” in summer 2010. After a year of additional efforts by a small group to impact policy through media and other channels (which did not move the needle), Martin Hellwig and I wrote the book The Bankers’ New Clothes, which explains the issues, including the confusing jargon, accessibly in the hope of enabling more people to participate in the debate and create political will to improve the rules.

The book received much praise and opened more venues for potential impact, but even with additional advocacy, the ultimate impact was limited. Despite the spectacular failures of pre-crisis regulation and the harm from the Great Recession, policy failures persist and flawed claims continue to obscure this fact and impact policy. The many enablers of the system, including academics, may have conflicted interests or stay passive to focus on more rewarding objectives and avoid politics and “controversy.” (Challenging people is not fun!) Often, however, they appear to display willful blindness and other forms of subtle capture, including what Sunstein called “epistemic capture.” The fact that the financial system did not collapse during the Covid-19 pandemic does not prove that it is resilient or efficient.

Even the purportedly apolitical and blind justice system is subject to the political forces that Stigler lamented. Michael Lewis ended his 2010 book The Big Short with a reflection on the persistent banking culture he first described in his 1989 book Liar’s Poker and the possibility that investment banks becoming public corporations (instead of partnerships) led to governance breakdowns and recklessness with other people’s money. The 2015 movie “The Big Short” brought up fraud and ended instead by noting that no executive went to jail after the financial crisis.

To be sure, much of the recklessness The Big Short book and movie describe was legal and tolerated by the flawed regulations in place. But fraud and deception were, and remain, pervasive in finance and beyond. As Vikramaditya Khanna explained, whether corporations and executives are held accountable depends on the legal system. Numerous examples suggest, as I discussed in this ProMarket post, that legal systems, particularly in the US, often fail to create proper accountability and deliver justice in the corporate context.

In a powerful recent book titled Why the Innocent Plead Guilty and the Guilty Go Free; And Other Paradoxes of Our Broken Legal System, Judge Jed Rakoff discusses the justice system in the US that he has observed from different perspectives for decades, and he points to political forces within this system quite related to Stigler and to the challenge of democracy in creating and enforcing proper rules. Rakoff laments that in the US “we imprison thousands of poor Black men for relatively modest crimes but almost never prosecute rich, white, high-level executives who commit crimes having far greater impact.” Rakoff aims, as Martin Hellwig and I did in writing our book, to educate and expand the circle of advocates for better policy.

Focusing on injustices that fall disproportionately on poor people, Rakoff explains how the system “too frequently convicts innocent people—often on the basis of dubious forensic science and shaky eyewitness testimony—and sometimes even coerces them into pleading guilty to crimes they never committed.” The underlying causes of this situation involve societal and political forces, including “tough on crime” attitudes and declared “wars” on drugs or terror, as well as the cost of legal representation and the incentives of individuals across the political and legal systems. Here again, the political processes distort the outcome.

Bad systems can persist when the issues are not salient to the public. Change requires that people in a position to challenge “the tyranny of the status quo” speak up and help to create political will for change. In the context of the justice system, as in finance, too many remain silent. Rakoff observes that among the enablers of the broken justice system are judges who fail to use their opportunities to speak up and hold power to account. Elected judges may find it politically unpalatable to appear “soft on crime,” but Rakoff forcefully challenges federal judges, who have lifetime tenure and are held in high regard by the public, to do more. Noting the inhumane treatment of people found guilty in the current system, he asks: “Unless we judges make more effort to speak out about this inhumanity, how can we call ourselves instruments of justice?”

The broad applicability of Stigler’s insights demonstrates just how much politicians, economists, and lawyers have in common, and how much we need to engage with one another across silos. Recent scandals such as Wirecard in Germany, Carillion in the UK, and Purdue and Boeing in the US, suggest that much remains to be done.

We cannot always trust that generic drugs work as promised, that children’s products are safe, or that our tap water is clean. Those who benefit at the expense of others and who can but fail to prevent harm prefer to obscure the facts, leading people to make false assumptions about the workings of the system and the trustworthiness of people and institutions. We are all victims of what Stigler described as “the pervasive use of state support of special groups” and of governance failures everywhere. But we should not be helpless.

It is on all of us, particularly unconflicted experts, to find ways to engage with the processes by which rules are written and enforced in the private sector and in government if we want markets, corporations, and democracy to serve society. By engaging, we can try to move the “imponderable” politics towards high moral goals and away from cronyism and corruption.