During the Second World War, economists at Iowa State College published a pamphlet titled “Putting Dairying on a War Footing,” which would later come to be known as Pamphlet No. 5. What followed was a months-long battle for academic freedom litigated throughout Iowa.

Editor’s note: The current debate in economics seems to lack a historical perspective. To try to address this deficiency, we decided to launch a Sunday column on ProMarket focusing on the historical dimension of economic ideas. You can read all of the pieces in the series here.

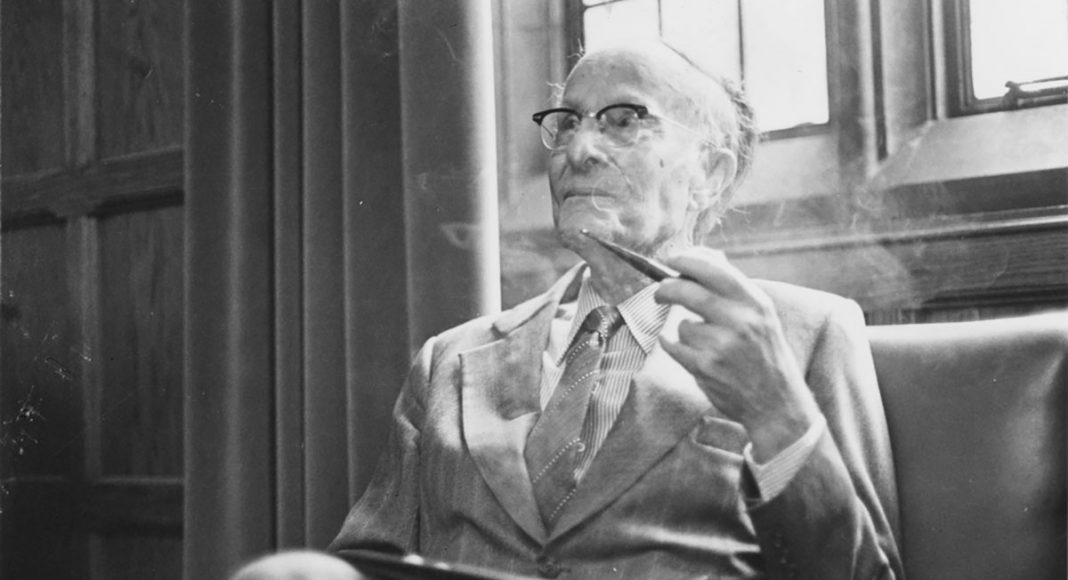

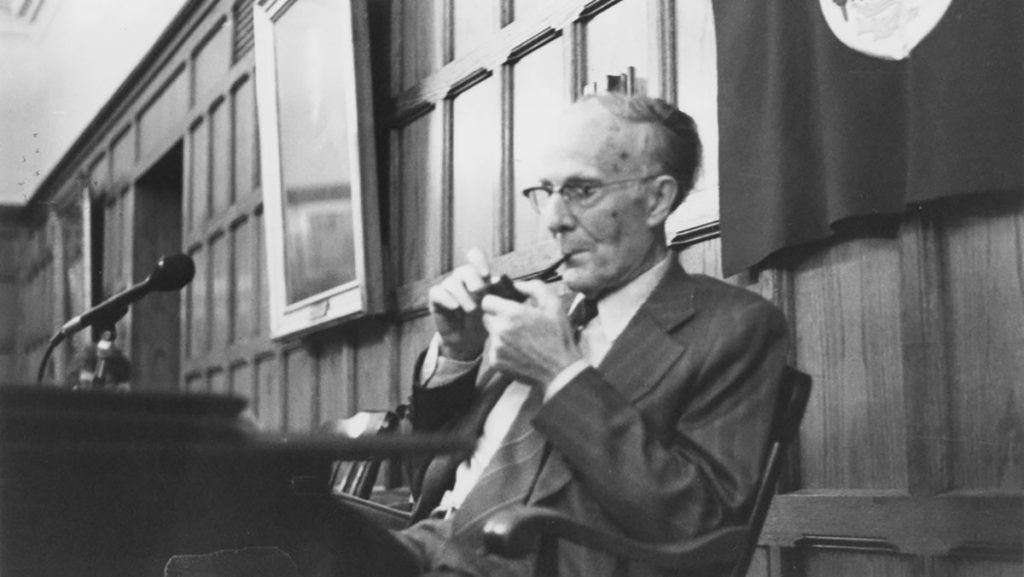

There used to be an “Ames School” of economics. At Iowa State College between about 1930 and 1945, a group of economists, led by then-identified “agricultural” economist T. W. Schultz, pushed two methodological experiments. One experiment, quite popular across Iowa, was the identity-crafting promotion of applied economics through making recommendations reaching all the way to grassroots decision-making. Iowa State’s economists analyzed economic and social forces to recommend rational strategies for various producer and consumer groups across Iowa. The other experiment, to assert academic freedom and to pursue intellectual honesty, proved more painful and unpopular than any other “school”-branding maneuver ever tried.

Yet, painful as it was, Schultz believed the assertion of such freedom, even if facing opposition from various groups, was the right thing to do.

One keenly interested group included Iowa’s dairy and butter producers, who were essentially financial supporters of Iowa State’s economists since their taxes passed through state channels to pay the economists’ salaries. To them, the fact that these economists would turn around and publish their conclusion that American consumers should directly purchase less dairy and butter products during wartime was viewed as the ultimate betrayal that could affect their livelihood.

However, as Schultz and others in Iowa State’s Department of Economics and Sociology understood free choice, among various assorted rights of academic freedom stood one essential right still unconfirmed: the freedom to pursue intellectual honesty. The butter-margarine test case for this, pursued through 1942 to 1944, attained notoriety far and wide. While professionally dangerous to the group’s very survival, that push was a matter of principle that Iowa State’s economists believed was beyond any moral hedging. What they pushed for, and accomplished, in effect, was to force-create some institutional structure capable of protecting autonomous space for social scientists to reach conclusions potentially opposite of what their financial supporters personally desire.

Their experiment in academic freedom led Iowa State’s economists into a situation so brutal that archived boxes are overflowing with preserved details about its casualties. These materials reveal how multiple strong personalities, divided into advocacy for conflicting goals, and with it imprinted on everyone that the unfolding situation threatened their job security, understood they were in a sense trapped. How so? Well, here is the general outline of it:

“Schultz believed the assertion of academic freedom, even if facing opposition from various groups, was the right thing to do.”

Schultz arrived at Iowa State College in 1930. Through some dozen years from that time, Schultz helped forge the school’s economists into a positive group identity. All of their research findings, with all expressed opinions and recommendations, whether implied or in increasing degrees overt, supported Iowans and their state’s economic interests. Schultz, widely respected and liked, appears to have been a unique force capable of encouraging or prodding a pretty good pre-existing group of economists to a whole new level of research, scholarly productivity, and excellence. All of this research and scholarship supported the agricultural interests of Iowans, who understandably gained deep trust in Schultz and Iowa State’s economists. Yet was such invariable support for Iowa interests merely an artifact of relatively easier times?

The Second World War was anything but an easy time. In October 1942, the US Secretary of Agriculture asked Schultz to guide Iowa State’s economists to develop a wartime national food policy. The idea was to introduce the policy through topical pamphlets. High-level administrators throughout the college signed their approval. Iowa State’s president provided his endorsement letter. The Rockefeller Foundation supplied a generous grant to help subsidize the publication and distribution of pamphlets, which would be published by the Iowa State College Press. Iowa State’s economists were expected—in words most concisely recorded by the Rockefeller Foundation—to produce “recommendations as to food production, distribution and consumption policies.”

Iowa State set to outlining, drafting, and producing 15 pamphlets. Between January and April 1943, the first four pamphlets all gained warm reception from the public. It was the fifth pamphlet, authored by doctoral student Oswald H. Brownlee, which would exact some damage just about everywhere, it seemed: morale pain and projected revenue loss to farmers, fractured relations between Iowa State and Iowa’s citizenry in general, a break-up of an entire economics group, and just possibly, some added piece in an accumulative public distrust of expertise. In the midst of all that, Iowans watched Schultz accept a new position at the University of Chicago.

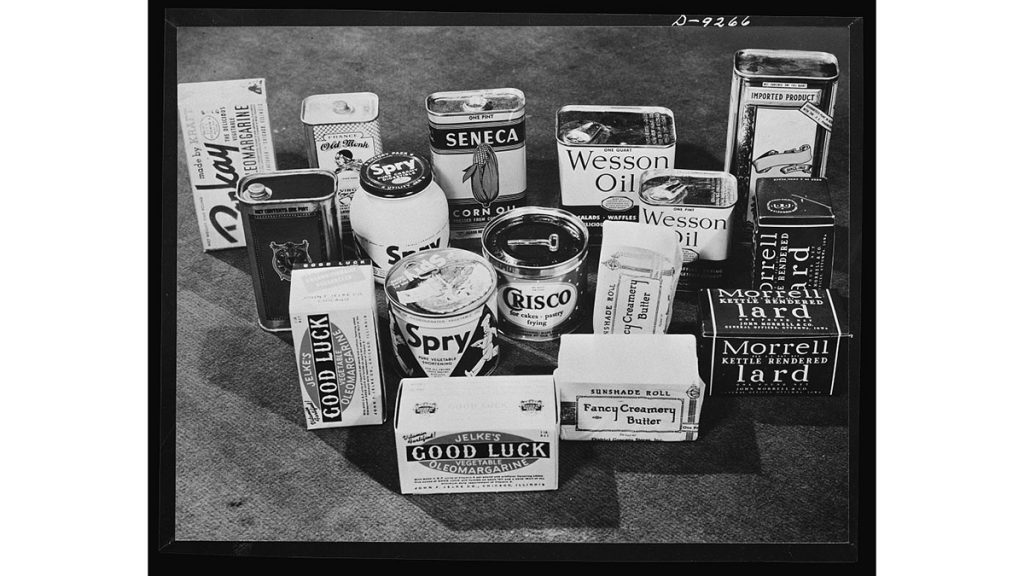

“Putting Dairying on a War Footing” was that fifth pamphlet’s title. Iowans called it “Pamphlet No. 5.” The policy objective assigned to Pamphlet No. 5 was to envision practical means for getting healthy dairy products to US soldiers. One identified means was for American households to substitute more margarine (then called oleomargarine) for butter, which would enable more milk to be used in less perishable forms. The pamphlet added that butter and margarine were roughly equivalent in taste and nutrition, which was a possibility that national dairy interests always nixed in concert. Such an admission, or just enabling such a belief, could only seem certain to harm Iowa’s farmers. Such an admission by Iowa State, to the sensibility of Iowa’s farmers, seemed criminal. Tax support from Iowa’s farmers paid the salaries of those who published that admission, and this crime seemed to merit punishment in the form of job firings. Iowa’s farmers took action, motivated by as deep and complex a sense of hurt, betrayal, and moral indignation as one can imagine.

The showdown would come to be known as Iowa’s Butter-Margarine War.

An avalanche of complaints soon buried the school’s president, who began ducking attempts by dairy leaders to meet with him. Stories and letters ran in industry journals and seemingly every newspaper in the state, with dozens of pieces published in the Des Moines Register alone. Colorful expressions and opinions came from both sides, in differing proportions, and in differing outlets, of course. In general, both sides tended to accuse the other of lies or hysterics. A meeting large enough to pack an auditorium was held on the Iowa State campus and was followed by so many convened committees, nearly all ad hoc, to require at least two hands to count.

Every one of these committees took a terribly long time to effectively do nothing, but long enough to appear as if they tried to do something. None of these committees were small in number either: “Special Committee” (five members); “Joint Committee” (twelve members—six from Iowa State and six from Iowa industries); a new pamphlet-review committee (five members); a committee to oversee retraction of Pamphlet No. 5; and, a committee to oversee rewriting of Pamphlet No. 5 (once it was officially retracted). These were just the initial few committees at Iowa State.

The Iowa Board of Education jumped into it, holding an emergency session about Pamphlet No. 5. Numerous position statements came forth, including from the National Dairy Council, the American Dairy Association, the National Dairy Union, and the Iowa Dairy Association. Iowa State’s administrators, who were not social scientists, formed their own committee to craft some definition of the role that social science should serve at their school, which they decided should only involve “factual” science.

Peripheral battles were next waged over the other pamphlets in the series—some of which were, on their own terms, almost as nasty as the central battle. Schultz held meetings with many people, including Iowa State’s president. A representative of the US Secretary of Agriculture contacted Iowa State to report that people in Washington liked Pamphlet No. 5. The Rockefeller Foundation chimed in saying likewise, as did the Social Science Research Council, an economist at Harvard, a farm management professor at the University of Illinois, a food researcher at Stanford University, and others as well.

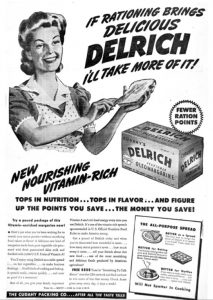

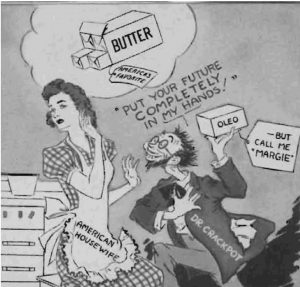

Butter supporters and margarine makers published clever advertisements, including a full-page item in the Des Moines Register on June 2, 1943, and a cartoon in the Creamery Journal in July 1943 depicting economics as “mad science”—each supporting their side while antagonizing the other. Newsweek covered the story, as did Time, Fortune, the Chicago Journal of Commerce, The New Republic, Reader’s Digest, and Harper’s Magazine.

The press was led to believe that a revised Pamphlet No. 5 was soon forthcoming, but behind the scenes nothing of the sort was happening. The president of Iowa State was busy dismantling and reconstituting the editorial board of the Iowa State College Press. The president also announced a “Committee to Reorganize the Department of Economics and Sociology” (four members, including no one from the department). It was right at that moment that Schultz resigned. Schultz delivered a lengthy letter, dated September 15, 1943, to campus officials as well as right into the newspapers. Among other things Schultz said, he told Iowans how this is a struggle worth having, as Iowa State must learn how to serve “first and foremost, the general welfare of the state and nation.” A week later in a letter to a friend (a letter now held in the University of Chicago archives), Schultz clarified that this struggle was an overdue effort “to do what needed to be done here.”

And with that, Schultz was gone. The state governor of Iowa responded to Schultz’s letter with a little press release reminding Iowans that he supported the president of Iowa State.

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) was watching the whole time. The AAUP announced that they might have to investigate “suppression of ‘academic freedom’” at Iowa State and did so soon after. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) then threatened their investigation. More committees were being created in-house, including Iowa State’s “Committee on Sponsorship of Publications” (five members).

So many vectors of stressors soon hit the same focal point: the committee to rewrite Pamphlet No. 5. Three months almost to the day from Schultz’s resignation letter, that committee fell apart. This happened after committee chairman George Godfrey resigned from exhaustion. At least that is what the press was told, but it was far worse than that: Godfrey, whose official position at Iowa State was an untenured one as assistant to the president, broke from the pressure. What really happened was that Godfrey’s heart gave out. Weeks later, in the hospital, he died. Iowa State’s president saw to it that the committee to rewrite Pamphlet No. 5 was reconstituted with multiple replacement members.

That reconstituted committee was renamed the “Committee on Review of the Manuscript of the Revision of ‘Pamphlet 5.’” The new chair of this reconstituted committee, a tenured professor of chemistry, was now the one under most stress. That chair’s do-nothing maneuvering was to stall, read a couple of rounds of possible revisions of the pamphlet, and then declare that Iowa State’s economists were impossible to work with. In light of that, the chair added, this committee must move, on its own, to disband itself. They all walked away.

It was then that one more new committee was established. That final committee, four members in total, would include the original author of Pamphlet No. 5. That committee was given no choice but to pound out and publish a revised Pamphlet No. 5. The procedural solution for Iowa State’s publication of social science at that point was a new caveat—basically, the dissenting opinion. Whoever might still object to what Iowa State’s social scientists said could just tack on a disavowing appendix, with one’s own name on it. The revised pamphlet was published, May 2, 1944, more than one full year after its initial publication.

Schultz was now nearing the end of his first year on faculty at the University of Chicago. He received a copy of the revised Pamphlet No. 5. He also received at least one additional mailing from Iowa State, a few months prior to that. Back at Iowa State, the Committee on Sponsorship of Publications finished its work, in draft form, by February 1944. The outcome (which would go into final form) was a 13-page policy statement. Iowa State provided a draft copy to Schultz, which is still in his archived papers. Iowa State’s policy statement included our modern understanding of publication methodology for social science: “There is no reason for committees or other formal proceedings before publication.” The statement added that “the desirable way to handle such publication is really that of scientific papers in general,” which could include peer assessment through “informal review by colleagues” at any level, including “in the wider field of international science.”

In retrospect, it seems impossible to believe that Schultz and others could not foresee that what they put into “Pamphlet No. 5” could potentially burn down the house. It did that and more. As Harper’s Magazine put it, in December 1943, it was an explosion that had “blown up the works.” In fairness to Schultz, how could any one person anticipate and imagine every potential point of battle that so many powerful and determined people could create for waging Iowa’s Butter-Margarine War?

To my knowledge, Schultz never chose to reflect in any published detail about what happened at Iowa State between October 1942 and May 1944. The whole situation must have been more painful for more people than he expected. Lastly—and not to take a thing away from what was happening worldwide during these years—in Iowa during 1942 to 1944 there really was a sort of war. When it was over, sixteen of twenty-six faculty members who were in Iowa State’s Department of Economics and Sociology in 1943 were no longer there by 1945. The postwar economy shifted towards policy opportunities for economists, of course. But there was more to it. At least six of those sixteen who left ended up, in different roles and for differing durations of time, at the University of Chicago.

Schultz, identified thereafter as an essential contributor to the “Chicago School” of economics, was at the Iowa State campus one October morning in 1979. At his room or while already at breakfast, he received a phone call. Schultz learned that morning that he had received a Nobel Prize.