India’s Covid-19 crisis is a reminder that Indian democracy is also in a crisis, partly due to an information ecosystem where facts and criticism are suppressed, hateful voices are amplified, and public conversation steers away from vital issues like health care.

India is currently facing a crushing second Covid-19 surge that is killing thousands of Indians every day. To understand how India got here, we must understand the weakening of India’s information ecosystem over the last few years.

Just before the current surge, the country started to open prematurely at a time when India’s mammoth vaccination drive had just begun. The country was in a jubilant mood, based on the belief that India was in its Covid “endgame.” While Covid-19 cases were already on the rise in India, on March 21, Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared in national front-page advertisements inviting people to Kumbh, a mass religious gathering of Hindus. Some seven million people attended. Then, on April 6, five Indian states and territories held elections where tens of millions of people voted. In mid-April, while thousands were dying each day, politicians continued to hold election rallies in the battleground state of West Bengal.

With Indians distracted by a deluge of scandals and conspiracies, public conversation on health care remained on the backburner. At the World Economic Forum’s Davos summit in January, Modi claimed to have strengthened India’s “Covid specific infrastructure.” Such claims received little public scrutiny. India’s Covid taskforce had stopped its regular meetings in the months that preceded the second wave. Hence, India was unprepared when the second wave of the pandemic, appropriately called a “tsunami,” hit the nation. When the country woke up, it was too late: There were no beds, no oxygen, no medicines, and even no crematoriums and burial grounds available.

Over the last few years, India has seen a new style of crisis management: the government relies on suppressing information on social media, and in the worst cases shuts down an area’s internet. Twitter’s transparency report shows a dramatic rise in removal requests from Indian government agencies (rarely made by the courts). Between the first half of 2018 and the first half of 2020, Twitter reported, such non-court requests increased elevenfold to 2,772—the company complied with 13.8 percent of these requests. In February 2021, a young climate activist, Disha Ravi, was arrested for sedition when she helped organize an international Twitter solidarity campaign supporting farmers who protested against a controversial farm bill in India. Hundreds of Twitter accounts and tweets were suspended by Twitter, as demanded by the government.

“Over the last few years, India has seen a new style of crisis management: the government relies on suppressing information on social media, and in the worst cases shuts down an area’s internet.”

Even at the height of the Covid-19 crisis, the suppression of information continues. To minimize negative coverage, the government once again ordered Twitter to censor several dozen critical tweets, and Twitter obeyed. Facebook temporarily blocked the trend #ResignModi, which trended on the platform as people expressed their anger, by “mistake.” Certain critical posts that the government labeled as “spreading misinformation” were removed from Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. In some states, the government tried to undermine the severity of the crisis by underreporting data and intimidating those who exposed the reality by pleading for help. In the city of Bhopal, the actual number of deaths in April are estimated to be 25 times more than the official figure of 109. To give a positive spin on the news, the Health Minister of India emphasized that India’s fatality rate was the lowest in the world—at a time when India’s Covid fatalities were the highest.

Twitter: Tool for Help—and Propaganda

Amidst all this, Twitter became a source of help for Indians, especially because a significant number of politicians, government officials, institutions, and influential figures are active on the platform. Twitter is akin to a town square, where the whole country is having a conversation. Tens of thousands of users tweeted SOS calls for help every day as they searched for beds, oxygen, or medicine for their loved ones; in many cases, the Twitter community helped them with important leads. Twitter has been a useful source of information during India’s pandemic crisis, as it helped match those in need with life-saving information.

Many crowdsourced efforts have been spearheaded by Twitter users to help those in need, but not all collective actions on Twitter are meant for the public good. For years, many Twitter accounts have collectively organized in India to promote extreme and hateful ideologies, diverting the public from urgent issues like public health. These accounts engage in coordinated Twitter campaigns and use Twitter’s “trending” topic feature to amplify their agenda. There exists no effective mechanism that Twitter uses to suppress dehumanizing trends that blatantly target entire communities.

“For a company like Twitter, with such advanced technical expertise, it is dangerously negligent to be incapable or unwilling to identify trends that target and dehumanize entire communities.”

A dangerous and orchestrated Twitter hashtag that trended nationally in India on February 29, 2020, was a call for an economic boycott (#आर्थिक_बहिष्कार) of the Muslim community, during the deadly Delhi riots. It was a sensitive moment for India as the country’s national capital saw a bloodbath that killed 53 people, the majority of them Muslims. During this sensitive time, Twitter became an amplifier of a call for economic boycott. This wasn’t the first time that a call for such boycott trended nationally—a similar trend (#मुस्लिमो_का_संपूर्ण_बहिष्कार) had trended nationally in India in October 2019 for a day. During the first wave of the pandemic in early April 2020 hashtags such as #CoronaJihad and “Muslims means terrorist” (#मुस्लिम_मतलब_आतंकवादी) trended nationally on Twitter, following reports of a Covid-19 super-spreader event in Delhi linked to an Islamic congregation.

For a company like Twitter, with such advanced technical expertise, it is dangerously negligent to be incapable or unwilling to identify trends that target and dehumanize entire communities. Suppressing such dehumanizing content does not require scanning millions of tweets, but just keeping a tab on those 20 odd hashtags/phrases that trend nationally on Twitter every day. But Twitter did not bother to even monitor its national trends, as verified far-right journalists tweeted calls for such boycotts. In contrast, in February 2021, when online activists made a hashtag #ModiPlanningFarmerGenocide in support of the farm law trend, Twitter blocked several accounts using the hashtag, following a strong reaction from the government.

There is no dearth of dehumanizing content on Twitter in India that is amplified each day, either as recommendations or as trends by Twitter algorithms. This creates a peculiar marketplace for ideas, where the most outrageous and outright dehumanizing content trends nationally and poisons the public conversation, while critical voices are suppressed. Such an ecosystem emboldens hate speech not just by anonymous trolls but also by verified personalities trying to capture this extreme audience.

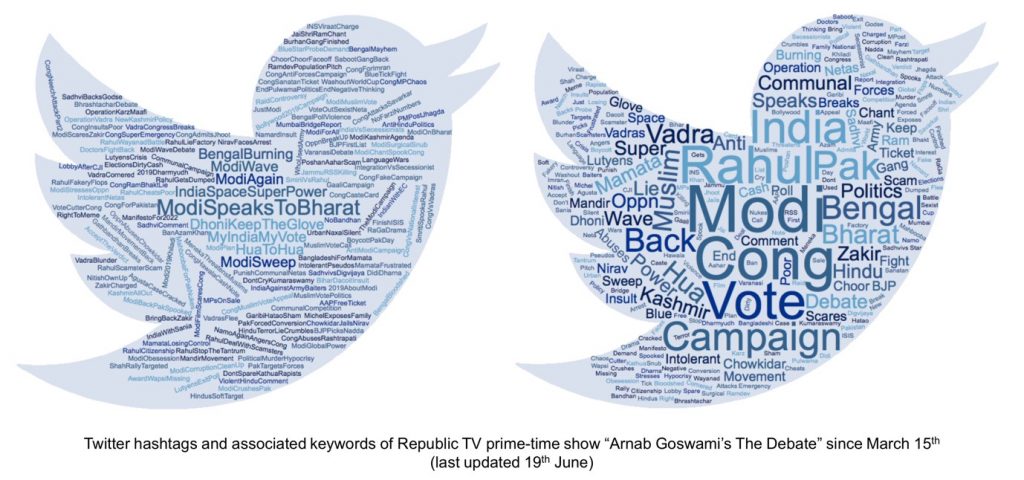

The real victim of this information ecosystem is public discourse on issues of governance. For example, during the 2019 Indian national elections, a pan-national survey of around 270 thousand voters (Figure 1) found that jobs, better health care, and clean water were the three most important issues for them. However, the primetime news in India did little coverage of such issues during elections. A word-cloud analysis of Twitter hashtags promoted during prime time by Republic, India’s most popular English news channel, (Figure 2) showed that these vital issues like jobs, health care and water found little to no coverage during elections, as opposed to hot-button topics like Pakistan, dynastic politics, and communal politics.

The Need for Better Algorithmic Regulation

Following far-right groups, other political and social groups have also begun organizing political campaigns on Twitter. While there is no dearth of diverse critical voices on Indian Twitter despite the attempts at censorship, the information ecosystem that Twitter amplifies is still filled with outrage, harassment, and fractionalization. As a result, the entire information ecosystem of India is being poisoned.

This is a concern that has been highlighted in the 2019 Stigler Center report (that I contributed to) on digital platforms and the media: Since digital platforms are legally considered carriers of information under the Section 230 exemption of the US Communications Decency Act, they lack the accountability for the content they feature or recommend through their algorithms, unlike traditional news media, which is legally accountable for every word it prints. The report finds that these giants enjoy a “hidden subsidy worth billions of dollars,” and at the same time enjoy immunity from the consequences of the content they trend and recommend.

Although Twitter has followed many censorship dictates of the Indian government, it still pretends to be an arena of freedom of speech. More realistically, Twitter is being used as a propaganda machine in India by competing groups, and its algorithms amplify orchestrated and visceral propaganda through its recommendations and trends. Twitter is not a passive party in India’s information ecosystem: Along with WhatsApp, Twitter is the favored platform for spreading misinformation, disinformation, and xenophobia in India. Both these platforms work very differently: Twitter editorializes its content, while WhatsApp chat rooms cannot be editorialized thanks to the end-to-end encryption. Hence, the solutions needed to improve both these information systems are distinct. As I wrote in a previous piece about WhatsApp’s misinformation problem in India for ProMarket, there is no one-size-fits-all policy that will work for all digital platforms.

Given the situation, regulators and policymakers, especially in the US, have a role to play. The American public should delve into the role US companies are playing in destabilizing democracies around the world by wreaking havoc on their marketplace for ideas. For example, in Myanmar, Facebook and its subsidiary WhatsApp have been used to spread hate against the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Although it may be difficult for social media companies to monitor every hate message on their platform, these digital giants are fully responsible for the content they feature or recommend. Ideally, these companies should have self-regulated themselves and should have never allowed hateful and dehumanizing content to trend and be recommended on their platforms. Unfortunately, companies like Twitter have failed to do so over the years. Hence, policymakers need to develop guidelines regarding what social media companies like Twitter can algorithmically showcase as trends and recommendations to their users so that they follow historically well-established journalistic guidelines of publication. If we fail to do so, a divisive information ecosystem would fractionalize nations around the world along narrow lines and hinder focus on things that matter, such as health care and public goods.