There are good arguments for getting rid of baseball’s long-standing exemption from antitrust laws, but the reason cited by Republican Senators angry at MLB’s response to Georgia’s new voting laws isn’t one of them.

Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX), Mike Lee (R-UT), Josh Hawley (R-MS), Marco Rubio (R-FL), and Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) propose getting rid of baseball’s longstanding exemption from the antitrust laws. They are not concerned about improving antitrust policy. Rather, they are upset that Major League Baseball pulled the 2021 All-Star Game out of Atlanta after Georgia passed legislation limiting voting rights. The Senators’ comments acknowledged as much: “If Major League Baseball is going to act dishonestly and spread lies about Georgia’s voting rights bill they shouldn’t expect to continue to receive special benefits from Congress,” Cruz said. Their statements went on to declare that baseball has enjoyed a special and very broad exemption from the antitrust laws that other businesses, including other professional sports, do not.

The Senators are correct about one thing: All the other professional sports, including football, basketball, automobile and horse racing, bowling, and others get along just fine without a similar exemption. Further, there are some good arguments for getting rid of it. The reasons for withdrawing an exemption matter, however.

The baseball exemption has a unique pedigree. It does not, as the Senators suggest, come from Congress. Rather, it originated in a lower federal court decision in 1920, and was confirmed by the Supreme Court’s 1922 decision in the Federal Baseball Club case. The newly created Federal League had attempted to develop its teams by making lucrative offers to players from the Majors. Their efforts collided head-on into the “reserve clause,” an anticompetitive labor agreement that limited players’ rights to move to another team even after their contracts had expired. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dismissed their antitrust challenge to the Clause. “Giving exhibitions of base ball,” he wrote for the Court, is not covered by the antitrust laws because “personal effort, not related to production, is not a subject of commerce.” The decision has been criticized for reflecting Justice Holmes’ ignorance about baseball and its commercial status, even in 1922. In fact, the decision was unanimous.

The exemption remains today, even though it is based on the fanciful conclusion that professional baseball, which generates more than $10 billion in annual revenue, is not “commerce.” In every other area where subsequent judicial rules expanded the scope of federal law passed under the Commerce Clause, antitrust decisions went right along with the expansion. For example, the Supreme Court decisively overruled earlier decisions, including antitrust decisions, that manufacturing trusts that ship their products across state lines were not reachable under federal law. Not so, baseball.

“The exemption remains today, even though it is based on the fanciful conclusion that professional baseball, which generates more than $10 billion in annual revenue, is not ‘commerce’.”

The GOP Senators’ proposal is hardly the first of its kind. Congress has entertained numerous efforts to repeal the baseball exemption, although as far as I can tell the other proposals were limited to resolving serious issues about the appropriate reach of the antitrust laws. The Supreme Court has noted these failed attempts in refusing to remove the exemption on its own.

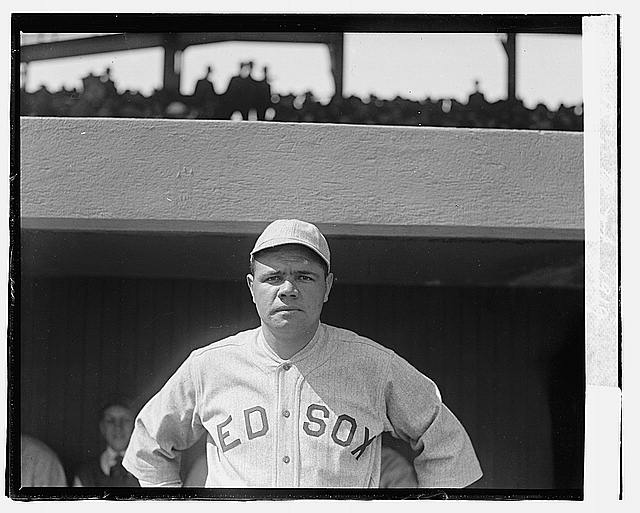

Repealing the baseball exemption would accomplish less than the Senators apparently presume. Most court cases that applied the exemption would come out the same way without it. Most are labor disputes involving things like salaries, retention, and the tradability of baseball players. An acknowledged purpose of the reserve clause itself, which was largely abandoned in the 1970s, was to keep salaries low by tying players to teams. The reserve clause prevented even Babe Ruth from moving to another team. He was able to leverage a raise only by threatening to retire and open a chain of workout gyms. The Clause produced another Supreme Court decision in 1953. George Toolson, a pitcher for the Newark Bears, a New York Yankees farm team, was effectively prevented from moving into the majors. The Yankees did not want him and the reserve clause prevented him from going anywhere else. Again in 1972 the Court applied the exemption, upholding the right of the St. Louis Cardinals to trade star outfielder Curt Flood. It also held that the reserve clause was not involuntary servitude forbidden by the Thirteenth Amendment, because he always had the option to just quit. Outside of baseball, unreasonably restrictive labor agreements are commonly challenged by the DOJ’s Antitrust Division.

Modern MLB labor agreements, although not most of those in the minor leagues, are contained in union contracts and involve mandatory subjects of collective bargaining—that is, wages, hours, working conditions, or conditions of employment. They are protected by the labor antitrust immunity, which exempts even collective bargaining agreements covering the entire league. One modest limitation is the Curt Flood Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton. That Act can be enforced only by players and makes baseball labor disputes with individual players subject to largely the same rules that govern other professional sports.

The baseball exemption has limited life outside of labor disputes. For example, in Right Field Rooftops, the court held that the baseball exemption applied when the Chicago Cubs built a giant scoreboard that obstructed the view from a neighboring apartment building. Its owner had been charging patrons to watch the game from its rooftop. But the exemption did not change the antitrust result: a firm ordinarily has no duty to share its assets with a competitor, particularly one who is free riding and depriving it of revenue.

Another area where repeal of the exemption could have some traction involves league decisions to control the number and location of teams. A 2003 decision held that the baseball exemption applied to MLB’s reduction in the number of league teams. A team reduction would almost certainly not violate the antitrust laws in any event. The court also held that the exemption preempted state law, but that is usually the outcome for networks such as national sports leagues where uniformity of law is important. Outside of baseball, the courts have held that a semi-professional team has no power to force its way onto the National Football League. One court did condemn the NFL’s exclusionary practices directed at the upstart US Football League, but it awarded only $1 in damages.

The baseball immunity does apply to league rules limiting the ability of teams (as opposed to individual players) to relocate, but most of these are not antitrust violations either. The anticompetitive exception occurs if a team was objecting to increased competition from having two teams in the same city. In that case, the baseball immunity might save an anticompetitive restraint.

Removing the antitrust exemption would have a small impact on the way that professional baseball is conducted, although it could limit a few anticompetitive practices. One thing it would not do, however, is to invalidate the Georgia voting rights boycott. The antitrust laws apply only to commercial boycotts, not to political ones. For example, a court rejected an antitrust complaint against the National Organization for Women for organizing a boycott of convention facilities in states that refused to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. The Supreme Court has also held that the First Amendment protected an NAACP boycott against stores that engaged in race discrimination. Even with the baseball exemption removed, the MLB boycott that angers the GOP Senators would remain untouchable under the antitrust laws. If the Senators want MLB to play in Georgia, they will have to repeal the First Amendment as well.