Lobbying on free trade agreements has been dominated by a few very large firms, which experience large gains as a result of the entry into force of these agreements. By contrast, losing firms have had no voice in the lobbying process, finding it too costly to be politically organized.

Recent decades have seen a proliferation of regional trade agreements. There are currently more than 300 of these agreements in force, most of which take the form of free trade agreements (FTAs). For example, the United States has 14 FTAs in force with 20 countries, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS). Multilateral rules require members of regional trade agreements to reciprocally eliminate “duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce” on “substantially all the trade” between them.

According to Dani Rodrik, FTAs “are shaped largely by rent-seeking, self-interested behavior on the export side. Rather than rein in protectionists, they empower another set of special interests and politically well-connected firms, such as international banks, pharmaceutical companies, and multinational corporations.”

Rodrik’s argument seems in contrast with the standard view that trade liberalization is opposed by import-competing interests who lobby in favor of protection. This standard view is elegantly captured in Gene Grossman’s and Elhanan Helpman’s “Protection for Sale” model and has been supported by several empirical studies. It should be stressed, however, that this literature is focused on unilateral and sector-specific trade policies, so domestic firms have nothing to gain from trade liberalization. By contrast, FTAs are reciprocal—allowing exporting firms to improve access to foreign markets for their final goods—and cover multiple sectors, reducing the cost of importing intermediate inputs.

Firm-level Lobbying on Trade Agreements

In a recent paper, we study theoretically and empirically how firms shape the political economy of trade agreements. The contribution of our paper is threefold. First, we build a unique dataset on firm-level lobbying expenditures on FTAs. Second, we provide systematic evidence that the politics of trade agreements is dominated by large pro-FTA firms, in line with Rodrik’s argument. Finally, we develop a new model of endogenous lobbying on FTAs by firms of different productivity, which can explain the observed variation in the extensive and intensive margin of firm-level lobbying on trade agreements.

We start by looking at the data, exploiting detailed information from lobbying reports available under the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) of 1995. The LDA requires individuals and organizations to file semi-annual reports providing information on their lobbying activities at the federal level and imposes significant civil and criminal penalties for violations of its requirements. All lobbying expenditures must be disclosed, no matter how small. Data on lobbying reports have been used in recent studies on lobbying.

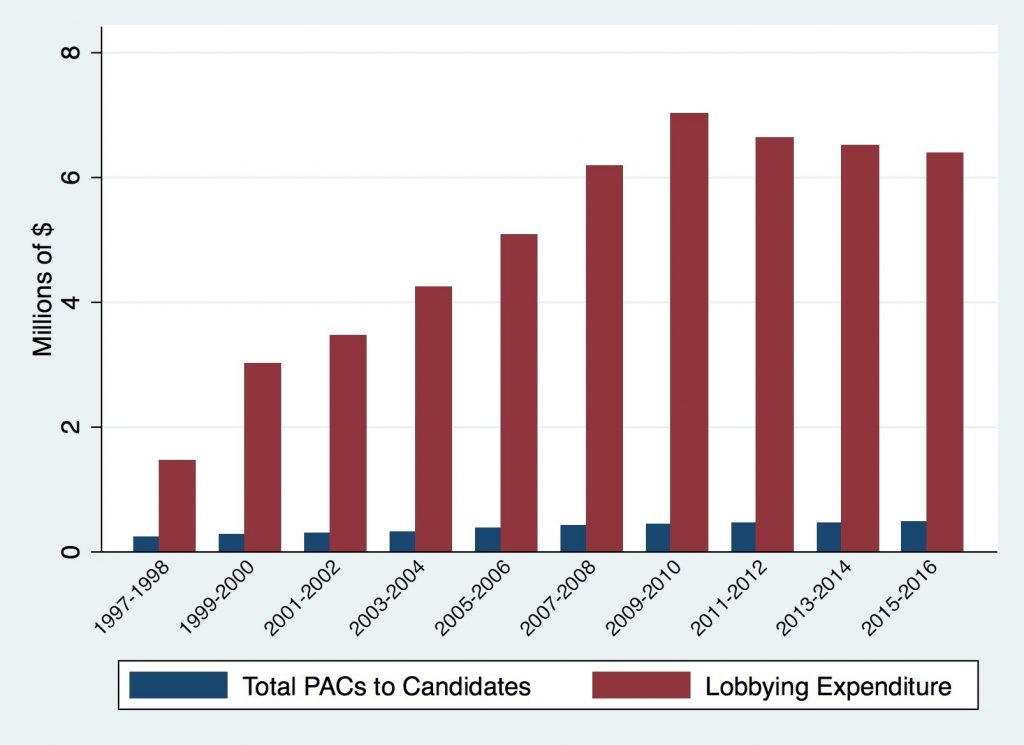

Using this data has two key advantages compared to the data on campaign contributions that were used in earlier studies. First, data on lobbying expenditures can be directly traced to the issues targeted by lobbyists, which is not possible for data on contributions. This is because the LDA requires disclosure of not only the amounts of lobbying expenditures, but also the issues for which the lobbying is carried out. Second, lobbying expenditures are the most important channel of political influence, more than ten times larger than PAC contributions (see Figure 1 below).

We have collected all reports related to the ratification of FTAs, but we focus on lobbying by individual firms, which are the key players when it comes to lobbying on trade agreements (total lobbying expenditures on FTAs by manufacturing firms is more than 10 times larger than spending by industry groups and 58 times larger than spending by unions). Our dataset provides information on the identity of the lobbying firm, its lobbying expenditure on a particular FTA, and whether it supported or opposed the agreement.

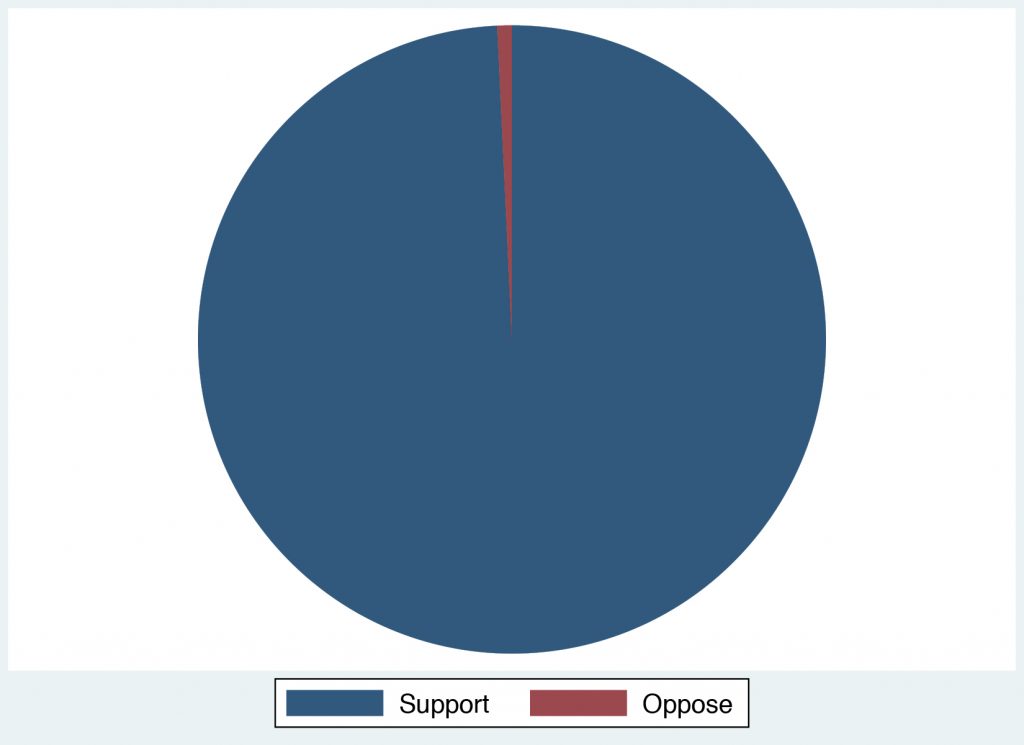

Using this dataset, we uncover new facts about firm-level lobbying on trade agreements. The most striking of these facts is that virtually all firms that lobby on FTAs support their ratification: in 99.25 percent of the cases, lobbying firms are in favor of the trade agreements (see Figure 2 below).

This is the first paper to show that lobbying on FTAs is dominated by firms that support these agreements, in line with Rodrik’s arguments. Also in line with his arguments, we find that firms that lobby on FTAs are larger and more internationalized (i.e., more likely to be multinationals, to be engaged in export and import activities, and to operate in tradable sectors) than non-lobbying firms.

Selection Into Lobbying by the Largest Winners

Our empirical findings cannot be rationalized by existing models on the political economy of FTAs, in which lobbying is carried out by industry groups or by homogeneous firms. Explaining why the politics of trade agreements is dominated by large pro-FTA firms requires a new model of lobbying by heterogeneous firms.

We thus develop a new model of the political economy of trade agreements, in which heterogeneous firms choose whether and how much to spend lobbying in favor of or against the ratification of a proposed FTA between two countries. The economic structure of the model allows us to study the distributional effects of the agreement, which leads to the reciprocal elimination of tariffs across all sectors.

We consider first the distributional effects of an FTA—which firms gain, and which firms lose from the agreement—in the canonical model of firm heterogeneity in trade. The entry into force of an FTA creates winners and losers. Non-exporting firms lose, since they suffer from the increase in competition in the domestic market and do not benefit from improved access to the foreign market. By contrast, exporting firms gain, with the most productive among them being the largest winners. Crucially, these “superstar” firms have higher stakes in the agreement than the biggest losers: their gains are larger in absolute terms than the maximum losses incurred by non-exporting firms.

In the canonical model, each individual firm has no mass and thus no impact on market and policy outcomes. We show that the key insights about the distributional effects of an FTA can be extended to models with heterogeneous oligopolistic firms, if large exporting firms are sheltered from losses in their domestic market, due to the presence of a competitive fringe or comparative advantage.

To model lobbying in favor of or against FTAs, we follow the literature on contests. Applied to trade agreements, lobbying in favor of or against the FTA in a contest game is made anticipating the impact of lobbying on the probability of ratification. This probabilistic objective captures the trade policy uncertainty emphasized in recent studies. In the absence of uncertainty, it would be hard to explain why firms may spend millions lobbying in support of agreements that do not enter into force (e.g., the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement).

We derive a condition under which only firms that gain from the trade agreement lobby. This condition is simple and intuitive: it requires that the marginal impact of lobbying on the probability of ratification is capped, so that only firms with the highest stakes in the FTA have incentives to lobby. Because firms with the highest stakes are also the largest and the most open to trade, our model predicts that only the largest exporters lobby on FTAs. The equilibrium features free riding: smaller pro-FTA firms that do not lobby benefit from the lobbying efforts of larger firms (operating in the same sector and/or in other sectors of the economy).

“Virtually all firms that lobby on FTAs support their ratification: in 99.25 percent of the cases, lobbying firms are in favor of the trade agreements.”

The model provides a simple explanation for why lobbying firms are always in favor of FTAs. It is also consistent with the other facts that emerge from our dataset: it can explain why lobbying firms are larger and more likely to be engaged in international trade than non-lobbying firms.

The Intensive Margin of Lobbying

We use the model to derive testable predictions about the determinants of firms’ lobbying on FTAs. First, larger firms should spend more lobbying in support of trade agreements. Second, individual firms should spend more supporting FTAs that generate larger gains—i.e., larger improvements in their access to foreign consumers and suppliers and smaller increases in domestic competition. Third, lobbying expenditures should increase in the probability that legislators are biased against ratifying the agreement. Intuitively, when politicians are more likely to be in favor of the agreement, firms tend to free ride on their political bias, thereby decreasing their contributions.

To assess the validity of these predictions, we exploit both cross-firm and within-firm variation in lobbying expenditures on trade agreements. In line with the first prediction, we find that larger firms spend more in favor of the ratification of a given agreement. In line with the second prediction, we show that individual firms spend more supporting FTAs that generate larger gains in terms of improved access to foreign consumers and suppliers and smaller increases in domestic competition. Finally, individual firms spend more in support of FTAs when US congressmen are less likely to be in favor of ratification, in line with the third prediction of our model.

Overall, our analysis shows that lobbying on FTAs has been dominated by a few very large firms, which experience large gains as a result of the entry into force of these agreements. By contrast, losing firms have had no voice in the lobbying process, finding it too costly to be politically organized.

Our findings support Rodrik’s view that trade agreements are shaped largely by rent-seeking, self-interested behavior of politically well-connected firms on the export side. They are also in line with studies focused on unilateral and sector-specific trade policies, which show that large firms lobby in favor of tariff reductions and resonate with arguments by political scientists, who emphasize that large pro-trade firms play an outsized role in trade politics. We see this paper as a first step in understanding how lobbying by heterogeneous firms can shape the politics of trade agreements. An important avenue of future research is to understand the extent to which firms shape the content of trade agreements.