In an interview with ProMarket, author and ProPublica reporter Alec MacGillis discusses the rise of Amazon and regional inequality, the role of politics in Amazon’s business model, the difference between Amazon today and Walmart two decades ago, and the ongoing attempts to unionize Amazon workers.

America today is a divided country. The biggest divide, however, isn’t so much between Republicans and Democrats—political divisions, despite recent spikes, are as old as the republic—but between those who are on the winning side of its economy and those who are (for lack of a better term) left behind. The last two decades have been characterized by a growing societal and economic chasm: on the one hand, a small number of large American cities, where much of the country’s wealth and prosperity have been increasingly concentrated; on the other, economically disadvantaged, post-industrial towns and rural areas plagued by declining incomes and living standards, displacement, and drugs.

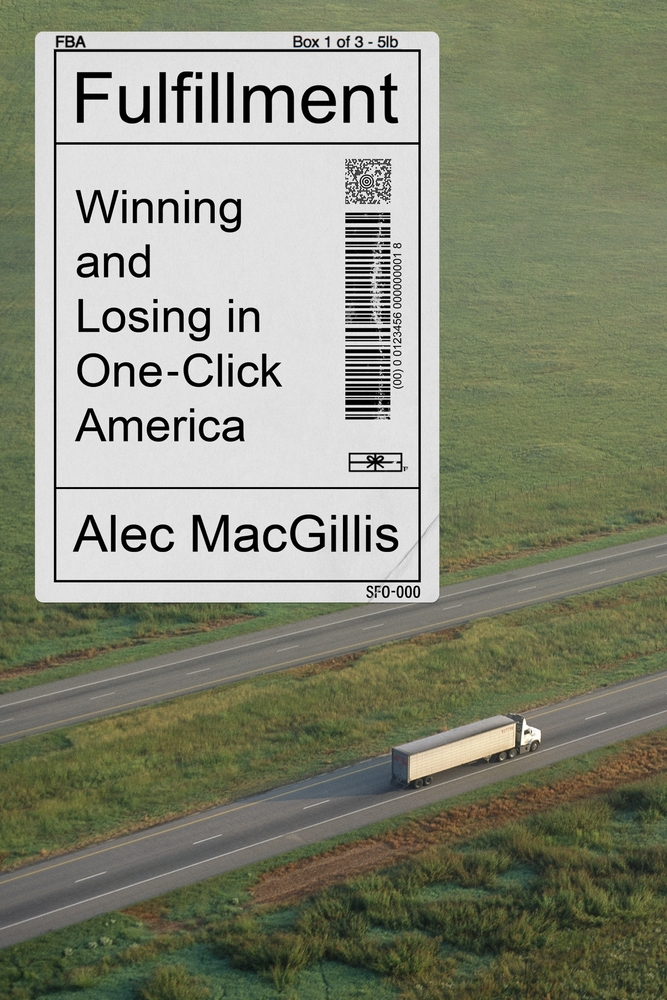

No company better embodies this gap than Amazon, argues Alec MacGillis in his new book Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America. While most of the company’s 800,000 US workers work in its “fulfillment centers” around the country, doing the sort of grueling warehouse work most recently highlighted by the unionization effort of Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama, the company’s headquarters in Seattle, Washington offers a decidedly different working environment, where employees “can think and work” in its ultra lush botanical gardens, a marvel of contemporary architecture.

What differentiates Amazon from other companies is its extraordinary, possibly unprecedented power over the American economy: not only does it control half of US e-commerce, but it is also a food retailer, a major producer and streamer of film, television, and digital content, a manufacturer of hardware, and major developer of facial-recognition technology. Its cloud-computing operation, Amazon Web Services (AWS), is so omnipresent that it’s virtually impossible to be online without relying on it. And its clout has grown even more since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic which, as Shaoul Sussman wrote last year, has made Amazon “inevitable.” Amazon, notes MacGillis, has hired 425,000 workers globally between January and October 2020; it opened 100 new buildings in September 2020 alone, and announcements of new warehouses and delivery centers are an almost daily occurrence.

But Amazon’s incredible success has left an enormous economic impact on America’s cities, argues MacGillis, both symptomizing the country’s vast regional inequalities and at the same time contributing to them. Fulfillment, the product of years of investigative work, is an exploration of an American economy reshaped by a wildly successful company, tracing Amazon’s influence from Seattle and Washington, DC, to post-industrial towns like Sparrows Point, Maryland, once hubs of stable middle-class employment and currently reliant on Amazon warehouse jobs.

We recently caught up with MacGillis, a reporter for ProPublica, for a conversation about the rise of Amazon and its impact on US inequality. In his ProMarket interview, MacGillis discussed the role of politics in Amazon’s business model, the difference between Amazon today and Walmart two decades ago, and the ongoing attempts to unionize Amazon workers.

[The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.]

Q: What did you set out to achieve with this book? Did it start as a book that focuses on Amazon?

No, it absolutely did not. I actually wanted to write a book about regional inequality. I have been going around the country all these years as a reporter, growing more and more dismayed by these growing disparities between places in the country. I think it really started during the Great Recession years, the early Obama years: I was out around the country a lot as a national political reporter for The Washington Post, and I’d be in the Midwest or Appalachia, going through one heartbreaking town after another. Then I’d come back to Washington and would be just overwhelmed by the prosperity and complacency there, and the disconnect from what was going on around the country. After Trump got elected, I knew that I needed to write about this issue, and I spent about a year figuring out what the right frame was, and then came to Amazon as the frame.

Q: Why did you decide to use Amazon as the frame? You’re surveying all these phenomena: extreme inequality and industrial concentration, the decline of American manufacturing, the unresponsive political system. What is Amazon’s role in all these?

For two main reasons. One is that it’s become so ubiquitous in the country. It’s just a handy thread to take you around the country as it now exists and the country that we’re now becoming, just because it’s everywhere. If you just follow Amazon, you’re in all of America. So in that sense, it’s almost like an expression or symptom of who we are. Its ubiquity and dominance in our life is a very clear expression of what we are now as a society and our insane inequalities: the richest man at the top, and the packers and cardboard box makers at the bottom.

But more than that, Amazon is also a contributor to regional inequality, to the extent that regional inequality is linked to the extraordinary concentration of wealth and prosperity in a handful of winner-take-all places. So that’s why it seemed like a good frame—it’s both a symptom and a cause.

Q: A lot of the charges relating to Amazon’s contribution to inequality or to the proliferation of low-wage jobs have been said before about another retail giant: Walmart. How is Amazon different than Walmart 20 years ago?

Its geographic effect is different. Walmart had this notorious, terrible effect on Main Street businesses in all these towns and cities around the country, especially smaller towns and cities. But it didn’t have as much of a geographic inequality effect because it wasn’t helping create these winner-take-all cities. The Walmart effect made one family grotesquely rich and benefited shareholders, but you didn’t have visible transformation of entire cities by the concentration of wealth that flows from this new model, the way you do with Amazon. So Amazon is both continuing to further undermine local commerce, in the footsteps of Walmart, and then on top of that it has created these manifestations of extreme wealth at the very top.

The other important difference is that Walmart, for all its depredations, pays infinitely more taxes than Amazon. It’s just tougher for them in their model to avoid taxes as effectively as Amazon has done.

“There’s a deep kind of affinity [toward Amazon] among the broader Democratic voter and consumer base.”

Q: One crucial aspect of the story that you tell that differentiates Amazon from Walmart is the role that politics plays in Amazon’s business model. Rather than a story about innovation, you tell the story of Amazon’s rise as something that has just as much to do with lobbying and with peddling influence and procuring government contracts. How crucial is politics to the Amazon model?

It’s very crucial. Early on, it really wasn’t so much about politics per se, as it was about playing the game to avoid taxes and gain a competitive advantage through that. It was all about that whole game of avoiding sales taxes, putting the company in Seattle to avoid having to pay sales taxes on purchases in California, and then making decisions about where to put warehouses based on avoiding sales taxes in large states.

More recently, it’s become very much about politics as the company basically realized that it was going to have a warehouse just about everywhere to fulfill the two-day and one-day delivery promises. Then it gets into this new game of aggressively pursuing tax credits and subsidies in exchange for deigning to build a warehouse or a data center in a given place. That’s when it gets much more aggressive in its overtures to local and state governments.

At the national level, it’s getting more involved in politics and peddling influence, both to keep its tax bill down at the national level and for the sake of the cloud business. When that becomes such a hugely lucrative part of the business, it becomes very important for them to start seeking those big government contracts. And that pursuit of the public sector government contracts for the cloud is what brings Amazon into national politics in a big way and kind of enmeshes it in Washington even before Bezos buys The Washington Post, before HQ2.

Q: For much of the time, Amazon’s political operation was mostly about pressuring local governments for tax subsidies and so forth. When did it start moving towards the national scene?

In 2009 or 2010 they had their first AWS public sector summit, which was held in DC. It was right around then that they really started seeking big contracts and being a big presence in Washington. Then Bezos buys the Post in 2013.

Q: You paint the acquisition of The Washington Post as part of a larger, orchestrated influence campaign. What was the role of the Washington Post purchase in terms of Amazon playing the Washington game?

I’m sure there was some sort of altruistic motive. It’s clear that Bezos does not have the strongest philanthropic altruistic motives in him generally, but he’s a serious enough reader and thinker that he knows how important the press is for a functioning country. So I definitely think he saw himself as serving some kind of higher purpose in restoring this great-but-sort-of-on-a-downslope paper.

But undoubtedly it was also just hugely helpful for the company when it was getting into the federal contracting realm in a much bigger way. When a company is getting so big that its biggest rival is not going to be other companies, but the risk of a federal intervention into its bigness, it’s of course hugely helpful to own the local paper. First of all, just for the goodwill that it brings, that you’re seen as kind of a defender of democracy and the free press. It gave Bezos an instant benevolent sheen. But it also put the paper in a really, really awkward position about doing really tough, comprehensive coverage of Amazon’s growing influence in Washington.

That’s the big problem: the Post has continued to cover various aspects of Amazon perfectly well. They’ve done tough stories here and there on various aspects of Amazon’s business operation. But the overarching story of Amazon’s takeover of Washington has not been told anywhere close to the way that needs to be done and the way that probably would have been done.

Q: Was this something you sought to correct with this book?

Definitely. I wanted to call people’s attention to the extent of their takeover of Washington and the story that I think is being missed.

Q: One interesting aspect is what happened inside the Democratic Party in regard to Amazon. In the book, you discuss the stigma that’s been created around accepting donations from Wall Street following the Great Recession, which coincided with the shift of the revolving door toward Big Tech firms, Amazon in particular, that didn’t have this stigma.

This is such an important issue now, as the Biden administration shows signs it is getting tougher on Big Tech. There’s this deep natural affinity between the Democrats and Big Tech at the elite level, where most of Silicon Valley’s political giving goes to the Democrats and you have this constant revolving door of people like Jay Carney going from the Obama administration to the tech companies.

But of course, it goes deeper than the elite. There’s a deep kind of affinity [toward Amazon] among the broader Democratic voter and consumer base. There was a poll from a couple of years ago that showed that Amazon is the most admired institution among Democrats in the entire country, ahead of the press, the unions, higher-ed, government. It’s third among Republicans, behind the military and cops. There’s market data showing that as universal as Amazon is, it’s definitely strongest among the big blue, metro, upper middle class demographic. Whereas Walmart still holds its own in redder, more rural areas, Amazon just crushes in the big blue cities. This is why there are giant piles of boxes outside your apartment building, spread on the sidewalks because the doormen are overwhelmed. And it’s gotten even more so this past year—that Democrats were in general far more cautious about Covid than Republicans meant there was even more of a shift to the one-click sort of existence among Democrats.

So the question whether to take on Amazon is going to prompt a very fascinating intra-left, intra-Democratic confrontation or reckoning. It’s not that the Republicans are irrelevant—the one reason I think that something might actually happen is that Republicans have their own motivations for going after Big Tech and are open to doing so—but the key question is what’s going to happen among Democrats.

“we’re back to square one, back to non-unionized jobs that should pay more, where workers have very little say, with an incredibly demanding employer with sort of grotesque wealth.”

Q: A lot of the stuff we’ve talked about so far isn’t treading new ground. American consumers know about the working conditions in Amazon facilities and so on and still love its low prices, the one-day or two-day shipping. If Amazon is reshaping America, it seems like American consumers seem happy to help.

Yeah, and this book is partly an attempt to get people to think more broadly about what’s happening to our country, and what’s behind the one-click and the seemingly low price and convenience. If this book has a target reader, it is the sort of highly educated middle/upper middle class left-leaning consumers who consider themselves liberal and concerned about the direction of the country, while unthinkingly going all in on this sort of a daily existence which, even beyond shopping and consumption, is a kind of withdrawal in a sense from the physical community around us.

Q: Your book went to press before the Alabama union vote, but you do cover other attempts at unionizing Amazon workers. What were the stakes in this vote? Why is Amazon fighting it so hard?

The odds were always long, but it’s understandable why they wanted to take a shot, because the stakes are huge. I was thinking about this in terms of the chapter about Sparrows Point and the fact that what happened in a place like Sparrows Point was that we had these incredibly difficult, grueling, low-paid, dangerous jobs, the steel mill in the early 20th century, and then, through organizing, these jobs were lifted up to something that was more middle class and sustainable.

And now we’re back to square one, back to non-unionized jobs that should pay more, where workers have very little say, with an incredibly demanding employer with sort of grotesque wealth. And so the question is really can we now lift up these jobs to a somewhat higher level, the way that they managed to lift up the steel mill jobs into something that can actually sustain a family in some kind of middle class existence.

Warehouse jobs are becoming the mass employment option for low-skilled, entry-level workers in this country in the way that the [steel] mills used to be. Can we make these jobs into something that is somehow more rewarding?

Q: Do you see the current moment as a moment of potential change in that regard? On the one hand, you have the pandemic that made Amazon so much bigger. And on the other hand, you have things like the Alabama vote and Lina Khan joining the FTC and Tim Wu in the National Economic Council.

I think it is a moment of incredible flux and a potential for change. My hunch is that the change might be easier to achieve in Washington than in the warehouses because Amazon is such a tough vote to beat in unionizing. It’s a moment of incredible potential right now.