Prescription drug shortages have become more common in recent years, interrupting usual medical care and increasing patient risk and system costs, but they are not inevitable. An independent nonprofit organization that creates standards for supply chain quality and routinely assesses and verifies manufacturer compliance with standards could promote a more resilient pharmaceutical supply chain.

Prescription drugs are the most commonly used form of medical care: 70 percent of the US population regularly take one or more prescription drugs. The vast majority of prescription drugs consumed are generic. Generic drugs are off-patent and chemically equivalent versions of branded, on-patent products. Generic drugs enter the US market after the patent for a new drug expires. Generic drug markets tend to be extremely competitive, resulting in lower prices for all purchasers. However, the experiences of consumers and organizations purchasing generic drugs suggest competition in some product markets has faltered over the past decade.

A paradigmatic example of one such market failure is drug shortages.

Drug shortages occur when the supply of a specific drug cannot meet its demand. This lack of available product requires some providers and patients to use less effective or more expensive treatment options. A recent report detailed how drug shortages have caused an estimated $359 million annually in additional health care spending due to increased labor costs alone. Shortages can also lead to increases in morbidity and mortality, such as when a shortage of norepinephrine in 2011 likely caused in-hospital mortality to increase significantly, and when a shortage of morphine in 2010 contributed to increased pain for many patients and medication errors that resulted in deaths.

Surprisingly, pharmaceutical shortages have become more common. Over the past decade, tens to hundreds of products have gone into shortage each year, and every year, a handful of products experience prolonged shortages that are even more costly. That shortages are now routine for many purchasers of drugs does not mean that they are inevitable. Rather, shortages arise from the imperfections that exist in the drug purchasing market.

The sale and purchase of generic prescription drugs in the US is accomplished within a complex ecosystem. Drug manufacturers sell to wholesale distributors, who in turn sell to pharmacies such as retail outlets or hospital-based pharmacies. Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) consolidate demand for drugs across hospitals, health systems, and payers and negotiate prices between their members and drug manufacturers. GPOs and PBMs were created to serve as an agent for their member hospitals, health systems, and payers whose main objective is to keep acquisition costs low.

Preventing drug shortages in the context of this complexity is challenging. Patients, pharmacies, and other purchasers do not have adequate tools and incentives to address drug shortages on their own. To address shortages, purchasers need holistic solutions that allow them to:

- Credibly identify which pharmaceutical products and manufacturers are less likely to experience shortages, and

- Benefit relative to their competitors from contracting with and purchasing from reliable manufacturers.

Currently, neither condition is met. Purchasers lack the ability to identify the pharmaceutical products that have reliable supply chains. Since buyers cannot verify which manufacturer’s product is “better,” manufacturers have little incentive to invest in quality and supply chain reliability. In addition, mechanisms that enable purchasers to benefit relative to their competitors from contracting with and purchasing from more reliable products are rare and often ineffective.

The simplest action a purchaser could take to address shortages—paying more for higher-reliability suppliers—costs the individual purchaser more but benefits all buyers by increasing overall reliability. An individual purchaser wants to see steady supply but does not want to bear the cost of creating that robust supply chain itself when other purchasers could free-ride on their decision. As a result, few purchasers unilaterally invest in identifying and purchasing from high-quality suppliers. Collectively, however, purchasers would be better off if they could share the cost of steady supply along with the benefits. When free-riding is not an option, purchasers will face a choice between a low quality product and one that is marginally more costly, but better for their overall bottom line and competitive position.

The last major obstacle is that the purchasing entities capable of coordinating across firms—such as GPOs and PBMs, along with pharmacies, hospitals, and the health systems themselves—do not fully internalize the cost of shortages. GPOs and PBMs often struggle to justify to their members why they should contract with more reliable suppliers that may supply these products at higher prices. GPOs and PBMs represent diverse members, some of whom are willing to pay a higher cost for reliable supply, and some of whom are not.

As GPOs and PBMs often see increased profits when higher-priced products are sold, they must be able to demonstrate through a trusted, independent third-party that they are truly contracting with reliable suppliers rather than simply boosting prices. Moreover, shortages cost hospitals and health systems in a variety of ways, from labor costs to being forced to use more expensive but similarly reimbursed treatments. While some costs from lower quality of care are borne by purchasers, many are borne by patients or payers.

“Over the past decade, tens to hundreds of products have gone into shortage each year, and every year, a handful of products experience prolonged shortages that are even more costly.”

Promoting Reliable, Transparent Information Exchange to Resolve Multi-Party Challenges

The optimal approach to addressing drug shortages must meet several conditions. First, a broad coalition of purchasers, providers, manufacturers, and other stakeholders should align on a set of robust best-practices for manufacturer reliability. Next, an entity acting on behalf of the coalition should assess which products and manufacturers meet the aligned-upon standards. To function effectively, the entity must be not only widely trusted by stakeholders from all parts of the industry but also be adept at standard creating and assessing compliance.

To complicate matters, manufacturers are wary of providing confidential supply information to purchasers who may leverage the information provided against poor suppliers without rewarding reliable suppliers. Manufacturers also are leery of losing a competitive advantage if confidential information is leaked to competitors or the general public, or of negative information harming their reputation. Despite these potential barriers, manufacturers could be incentivized to increase transparency into their supply chains. A major paradox of drug shortages is that the medicines in shortage are often life-saving or life-sustaining, yet at the same time are often off-patent and inexpensive. This paradox suggests that the medicines in shortage are severely undervalued by the market, and manufacturers are acutely aware that the pricing of these products does not reflect their true value to public health.

If provided with strong assurances of confidentiality in specific proprietary areas, as well as rewards for making investments in reliability, high-reliability manufacturers would benefit from participating in transparent third-party evaluations of their supply chains. Ultimately, manufacturers know that differentiation between suppliers of generic medicines is the only way to unlock the true value of these critical medications.

Drug shortages could potentially be addressed by the government. The FDA has taken numerous corrective actions such as carrying out robust site inspections, developing a list of essential drugs, requiring manufacturers to disclose when they expect a shortage to occur, and tracking ongoing shortages. However, these efforts have not been sufficient in preventing shortages from occurring.

The FDA Drug Shortages Task Force report, published in 2019, which was prompted by a letter from over 130 members of Congress, highlighted many of the root causes of drug shortages mentioned in this white paper, along with proposed solutions such as developing a rating system to incentivize drug manufacturers to invest in reducing drug shortages. To this end, the FDA is advancing the development of its “Quality Management Maturity” model. Under this program, the FDA plans to not only evaluate whether manufacturers are complying with regulations, but whether they are taking sustained and systematic steps to measure and address quality issues that could lead to drug shortages. However, government efforts to date have not produced a comprehensive solution to drug shortages.

Recently-formed organizations such as the nonprofit generic drug manufacturer CivicaRx have also taken positive steps by aggregating demand and guaranteeing purchases to manufacturers and supply to members, thus ensuring the purchasers paying for reliability benefit from that reliability. However, the problems of identifying which manufacturers and products truly have robust supply chains and adequately strengthening purchase commitments remain unsolved.

The Role for Non-Profits: Rating Pharmaceutical Quality and Supply Chain Reliability

We believe the solution is clear: an independent nonprofit organization that creates standards for reliability, assesses and verifies manufacturer compliance with those standards, and communicates reliability assessment outcomes to the market.

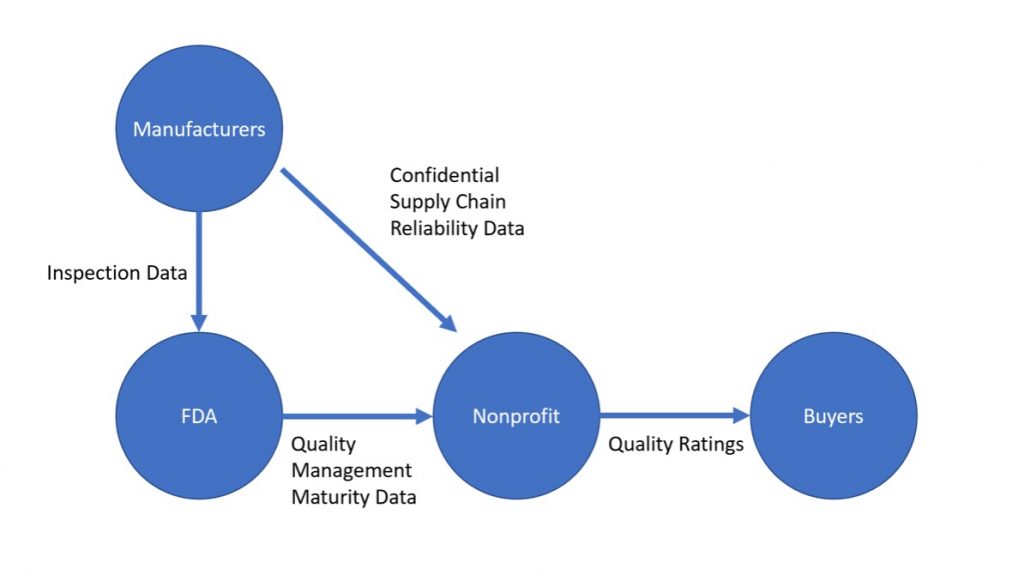

Proposed Rating System Information Flow:

The concept of certification is neither new to the world nor to health care. Successful nonprofit rating organizations, such as URAC, ISO (International Organization for Standardization), and Joint Commission on Hospital Quality, already assess the extent to which specialty pharmacies, manufacturing processes, and hospitals comply with a set of standards around quality, safety, and other metrics. These programs have been implemented to spur investment and correct market inefficiencies in health care and other industries and have been largely successful. Similarly, our proposed nonprofit rating organization must be able to convene relevant stakeholders to develop standards that are achievable and correlate with reliability. The organization must also be able to claim objectivity, and as a result ought to be a nonprofit funded transparently in ways that avoid conflicts of interest.

When making pharmaceutical contracting and buying decisions, purchasers use reliability metrics that are self-reported by manufacturers. This approach means that currently every purchasing entity is responsible for individually acquiring and vetting reliability information. However, the utility of reliability information provided by manufacturers is inconsistent, as purchasers often do not have the capabilities or resources to verify the accuracy of the information that is provided.

To overcome this problem, a trusted nonprofit could facilitate an information flow of reliability metrics between manufacturers and purchasers, while keeping certain sensitive business information confidential. This approach reduces the cost for purchasers of acquiring reliability information and creates opportunities for more thorough verification and widespread use of the information than exists today.

The nonprofit could also assess quality and reliability through additional verification methods, similar to how the Joint Commission on Hospital Quality conducts hospital certifications. While few firms seek greater oversight by choice absent a strong market incentive, if purchasers demand this information and are willing to reward manufacturers who go through the process, the benefits of certification can outweigh their costs for reliable, high-quality manufacturers.

Furthermore, mechanisms to ensure that purchasers who sign guaranteed purchase agreements from highly-rated suppliers are first-in-line for product when a shortage occurs would be necessary to properly align incentives and address the final barrier to implementation. For example, as part of membership in this organization, purchasers could potentially be guaranteed supply from manufacturers deemed to be highly reliable in the event of a shortage.

By having this organization provide certification information to purchasing groups while serving as a safe clearinghouse for confidential information valued by manufacturers, it can solve the transparency and trust problems. And by comprising the organization of stakeholders from relevant backgrounds, including from health systems, GPOs, and manufacturers, it can choose standards that are both effective in reducing shortages and feasible for manufacturers to implement.

Disclaimer: Adam Kroetsch receives grant support and consulting fees from the FDA. Stephen Colvill is a part-time Research Associate at the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy.