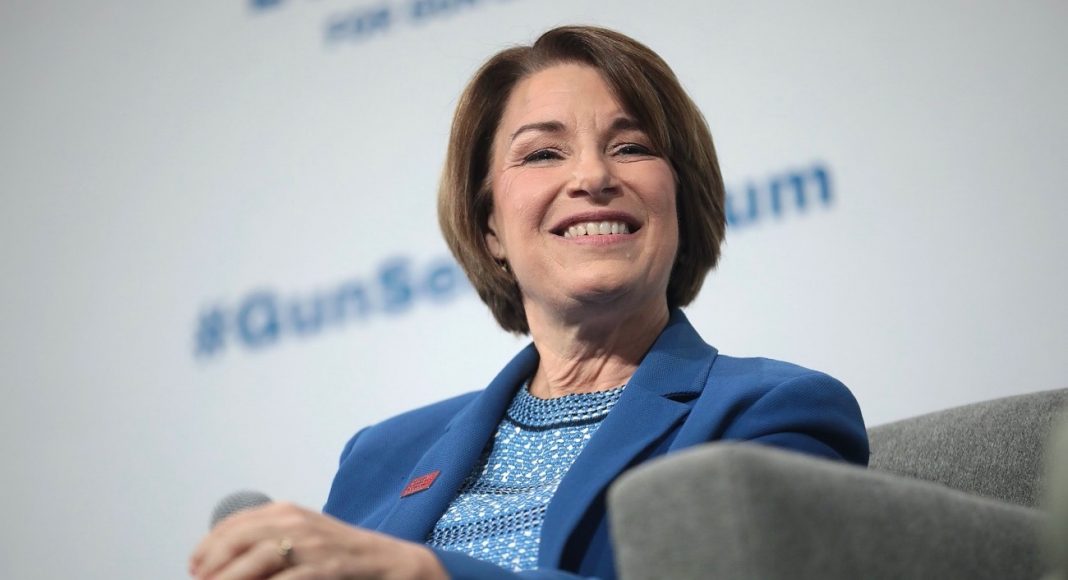

The antitrust reform bill recently proposed by Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) purports to fix problems caused by antitrust courts’ reliance on “inaccurate economic assumptions.” But the bill itself would enshrine unsupported assumptions into antitrust law.

There’s an irony in Senator Amy Klobuchar’s (D-MN) recent antitrust reform bill. At its outset, the bill states that antitrust enforcement

“has been impeded when courts have declined to rigorously examine the facts in favor of relying on inaccurate economic assumptions that are inconsistent with contemporary economic learning….”

The bill’s two most significant provisions, however, would themselves truncate factual analysis and enshrine “inaccurate economic assumptions” into antitrust doctrine. If those provisions become law, error costs from antitrust enforcement will grow, reducing social welfare.

The two provisions I mention would tighten restrictions on mergers (Section 4) and shift the burden of proof in many exclusionary conduct cases (Section 9). To see why each is misguided, consider briefly antitrust’s central dilemma and the optimal way of addressing it.

Antitrust’s Dilemma and How Best to Address It

Most of the business behaviors antitrust addresses are “mixed bags”: practices, like exclusive dealing and discounting arrangements, that are sometimes good (output-enhancing) and sometimes bad (output-reducing).

Regulating mixed bags is tricky, as the regulator can wrongly forbid good instances of a behavior (a Type I error) or wrongly permit bad instances (a Type II error). Attempts to avoid Type I errors tend to generate Type II errors, and vice-versa. And if the regulator creates more complicated liability rules in an effort to reduce both sorts of errors simultaneously, the costs of deciding what is allowed or forbidden—costs that must be borne by both business planners and adjudicators—will grow. As in a game of whack-a-mole, driving down one set of costs causes another to rise.

In light of this unhappy situation, antitrust standards should be crafted with an eye toward minimizing the sum of error costs (both Type I and Type II) and decision costs.

To accomplish that end, antitrust standards should be based on the best theory and evidence available, and proof burdens should be allocated to minimize the losses from “proof failure”—a situation in which the available evidence establishes neither the existence nor absence of some element. For example, if economic theory, confirmed by empirical evidence, shows that a practice is likely to reduce market output only if conditions a, b, and c are satisfied but would likely enhance market output under condition x or a combination of conditions y and z, the court should assign liability only upon a showing of a, b, and c and the absence of either x or both y and z. And to account for proof failures, the court should generally assign the burden of proving an element or its absence to the party with a lower likelihood of success. Because a proof failure results in victory for the party who does not bear the burden of proof, such an assignment will reduce the likelihood that a proof failure will generate an erroneous judgment and the resulting error costs.

The two main provisions of Senator Klobuchar’s bill flout this common-sense approach to addressing antitrust’s central dilemma.

“In the end, Senator Klobuchar’s bill may create the very problem it purports to correct.”

Enhancing Merger Restrictions

Under current law, a business merger or acquisition is illegal if it is likely “substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly” in some market. The party challenging the merger—usually one of the federal enforcement agencies—has the initial burden of proving that the merger is likely to have the forbidden effect, though the likelihood of such an effect may be presumed if the merger will result in substantial market concentration. The burden then shifts to the merging parties to prove that, despite the resulting level of concentration, the merger is unlikely to lessen competition substantially, typically because of productive efficiencies occasioned by the merger or a likelihood of market entry in response to higher prices.

Senator Klobuchar’s bill lowers the standard for forbidding a merger and shifts proof burdens in many merger challenges.

With respect to the liability standard, the bill amends Section 7 of the Clayton Act to forbid any merger where the effect “may be to create an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition” in a market, and it defines “materially” to mean “more than a de minimis amount” (which presumably means not so small that it could be considered insignificant). The bill thus changes the dispositive question in merger cases from “Is it more likely than not substantially to lessen competition in a market?” to “Is it more likely than not to create an appreciable risk of reducing competition in some market by more than a de minimis amount?” Assuming that a risk’s appreciability turns on its magnitude and that the risk of an event becomes appreciable when there is, say, a 15 percent chance of the event’s occurrence, a merger would be prohibited whenever there is a 50 percent chance that it would produce at least a 15 percent chance of causing a non-trivial reduction in market competition. That is a remarkably low standard for forbidding a business combination.

In merger cases brought by the government (including state attorneys general), Senator Klobuchar’s bill presumes that the standard for condemnation is satisfied under certain circumstances. Two grounds for invoking the presumption of illegality—and thereby shifting the burden of proof from plaintiff to defendant—turn on the sheer size of the merging companies: (1) where the company being acquired is worth at least $5 billion and (2) where the acquiring company is worth (or has annual sales of) at least $100 billion and is acquiring a company worth at least $50 million.

These size-based presumptions sweep broadly. At present, more than a thousand US companies (public and private) are of a size where their acquisitions—regardless of the buyer—would trigger a presumption of illegality. Nearly 100 US companies have market capitalizations or annual sales at a level where their attempted purchase of any company worth a mere $50 million—a paltry amount in the merger context—would do so.

Once triggered, the presumption of illegality is difficult to rebut. The merging parties, according to the bill, must “establish, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the effect of the acquisition will not be to create an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition.” Given how easy it is to conceive of theories under which a merger might barely soften competition, it would be exceedingly difficult for merging parties to prove the absence of any appreciable risk of reducing competition by more than a de minimis amount. As a practical matter, then, Senator Klobuchar’s bill all but forbids mergers based solely on the size of the merging firms, regardless of whether anticompetitive effects are likely to result.

Such a rule is inconsistent with the optimizing approach set forth above. That approach calls for prescribing elements of liability based on what we know, from economic theory and empirical evidence, about when anticompetitive harm is likely. It makes sense, for example, to focus on how a merger under review affects market concentration, for both economic theory and empirical evidence suggest that mergers leading to concentrated markets are more likely to occasion anticompetitive harm. By contrast, neither economic theory nor empirical evidence suggests that a merging firm’s sheer size—whether measured by market capitalization, asset value, or annual sales—has anything to do with the likely competitive effects of the merger.

In setting forth liability rules that turn on size factors alone, the proposed reform injects inapposite matters into the analysis. And in basing proof burdens on those matters, rather than on the relative plausibility of pro- versus anti-competitive effects, the proposed approach further fails to structure the inquiry appropriately. The prevailing approach, which assesses mergers based on probable competitive effects and considers only matters shown to be probative of those effects (e.g., market concentration, the likelihood of entry, productive efficiencies, etc.), is less likely to generate welfare-reducing errors than is an approach that injects irrelevant considerations and misallocates proof burdens.

Shifting the Burden of Proof on Exclusionary Conduct

Senator Klobuchar’s bill also makes it illegal “to engage in exclusionary conduct that presents an appreciable risk of harming competition.” The bill defines “exclusionary conduct” as conduct that “(i) materially disadvantages 1 or more actual or potential competitors; or (ii) tends to foreclose or limit the ability or incentive of 1 or more actual or potential competitors to compete.” The bill then provides that such conduct “shall be presumed to present an appreciable risk of harming competition” if the company engaging in it has a market share exceeding 50 percent or “otherwise has significant market power” in the relevant market. The upshot is that any firm possessing either a market share of greater than 50 percent or significant market power is presumed to have broken the law any time it takes an action that materially disadvantages or forecloses an actual or potential rival.

That presumption would apply quite often. The market power element would frequently be satisfied, as the proposed act defines market power as the ability to profitably price above incremental cost (the level that would prevail in a competitive market) and would thus sweep in a great many firms participating in brand-differentiated markets, where above-cost pricing is common. The material disadvantage/foreclosure element would be satisfied by any conduct—including price cuts and product improvements—that would usurp business from rivals, thereby “disadvantag[ing]” them, “foreclose[ing]” them from available sales opportunities, or limiting their ability to compete.

Suppose, for example, that a manufacturer of a high-margin branded product offered retailers an attractive volume discount in order to grow its market share. The manufacturer’s high profit margin would evince market power, and its volume discount would tend to “foreclose” its rivals from retailer shelf space. Its discount, which would lower consumer prices and increase output, would be presumptively illegal. The manufacturer would thus bear the burden of proving that its discount is pro-competitive—a burden that would be heavier under Sen. Klobuchar’s bill, which abrogates the prevailing safe harbor for discounts that result in above-cost prices.

Saddling firms—even big ones and those able to charge above-cost prices—with the burden to prove that their sales-enhancing initiatives are pro-competitive hardly seems justified in light of common experience. Is it not obvious that most of the things firms do to enhance their sales (to the detriment of their rivals) involve sweetening the price/quality combination for consumers? Since anticompetitive exclusionary conduct—even among firms with high market shares and significant profit margins—is less common than competitive, consumer-benefitting actions that incidentally disadvantage rivals, it makes no sense to require proof of pro-competitive effect whenever a rival is disadvantaged or foreclosed. To reduce enforcement errors, the burden of proof should be allocated to the party with the less likely story.

In the end, then, Senator Klobuchar’s bill may create the very problem it purports to correct: By positing presumptions of anticompetitive harm that are not based on economic evidence, it effectively directs courts to “decline to rigorously examine the facts in favor of relying on inaccurate economic assumptions.” It is thus likely to generate high error costs that will reduce overall social welfare.