The Biden administration should work to reverse the declining morale since a re-energized Antitrust Division will translate into more effective, innovative enforcement efforts.

The US Department of Justice Antitrust Division faces one of the most critical junctures in its long and storied history. A landmark case against Google, high concentration levels across a variety of industries, a projected wave of merger-driven consolidation, and an increasing likelihood of legislative reforms—amidst all of these, a healthy and robust Antitrust Division has never been more necessary.

So it’s been especially troubling to see the drastic decline in Division morale over the past four years. In 2010, when I was a summer intern there, the Antitrust Division prided itself on being one of the best places to work in the entire federal government. That year, the Division ranked 22nd out of over 400 federal agency components included in the Office of Personal Management’s (OPM) annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey.

But per the OPM’s latest results, morale at the Antitrust Division has plummeted, dragging the Division all the way down to 404th place out of the 420 agency components surveyed.

Let that sink in: morale at the Antitrust Division dropped from a consistent top 10 percent ranking to a bottom 10 percent ranking in less than a decade.

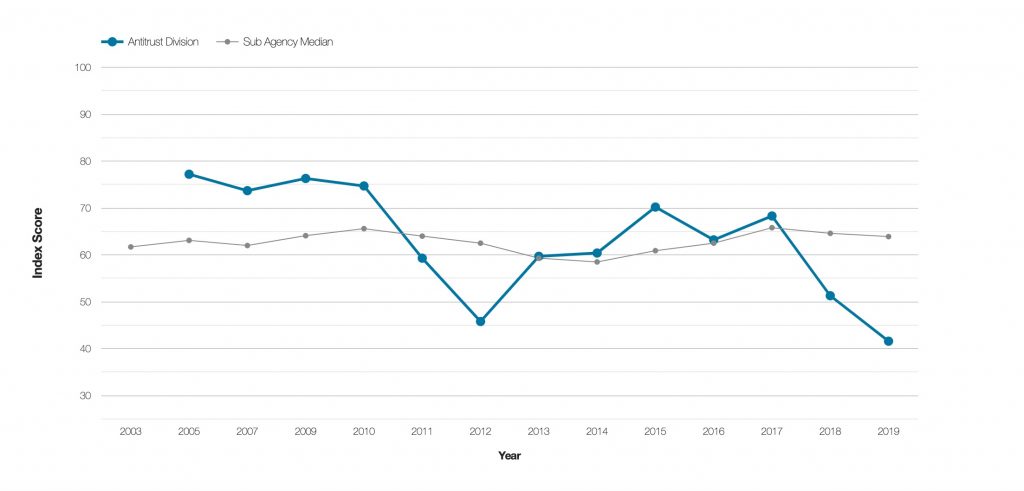

This can’t be explained away by an overall drop in morale at the Justice Department. It is specific to the Antitrust Division. The blue line below represents the Division; the gray line DOJ more broadly.

After a temporary drop during 2011–12 (likely due to an internal restructuring effort), a marked divergence began in 2017. Over that time period, as highlighted by the New York Times, the Division was among the ten agencies experiencing the worst declines in employee morale.

At the same time, antitrust law itself has skyrocketed in visibility. A well-functioning Antitrust Division is always important—these days, it’s crucial.

What’s to Be Done?

The Biden administration faces both challenges and opportunity. Citing interagency dysfunction between the Division and the FTC over the past four years, a number of observers have proposed stripping antitrust jurisdiction from one of the agencies. But why not fix existing structures instead of simply tossing them aside? Practicing with the Antitrust Division should be a positive, fulfilling experience. And, just as importantly, a re-energized Division will translate into more effective, innovative enforcement efforts.

Instead of giving up, let’s “build back better.” Here’s how:

Recommendation # 1: Select an Assistant Attorney General with proven dedication to strong antitrust enforcement.

Change starts at the top. The ideal AAG for the current moment is someone who has a proven track record of dedication to strong antitrust enforcement. Past employment choices should not necessarily disqualify anyone from consideration, but a track record of choosing to work for antitrust defendants can hinder the Division’s mission. For example, consider DOJ’s recent defendant-friendly intervention into FTC v. Qualcomm. It was widely reported at the time that then-Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim had been a lobbyist for Qualcomm shortly before taking over the Division’s helm in 2017. Nothing in the public record suggests that anything unethical occurred behind the scenes, and Delrahim had recused himself from the matter. But, unsurprisingly, the former lobbying connection provoked considerable doubt about the Division’s motivations.

In the wake of DOJ’s landmark complaint against Google, this pattern repeated itself. Again, one of Delrahim’s former clients was in the antitrust crosshairs. Again, he recused himself, albeit months after the investigation was already underway. And again, the ties between the Division chief and a former client were enough to overshadow the merits of the Division’s actual case. Enforcers found themselves under a political cloud.

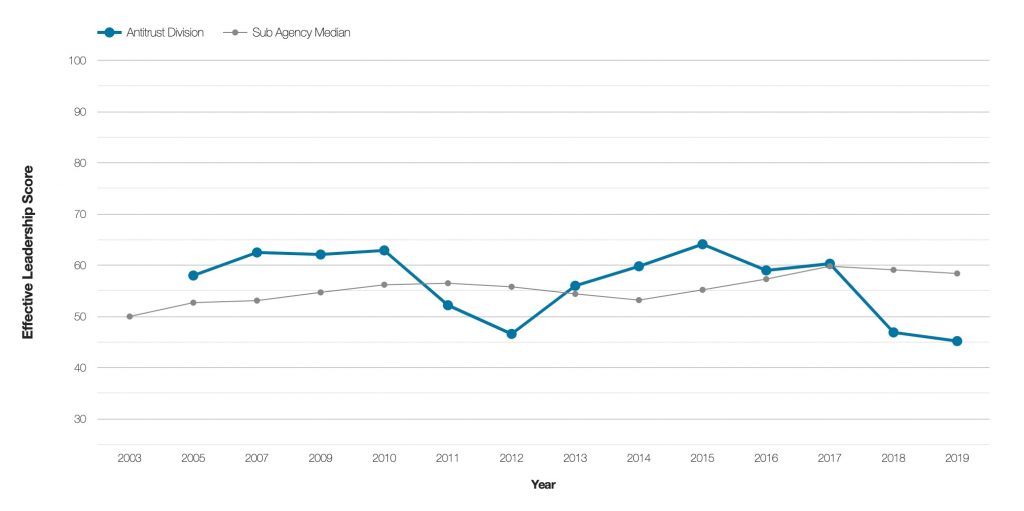

The OPM’s survey results indicate that perceived lack of “effective leadership” is currently a contributor to flagging Division morale.

Even if an AAG is recused from all matters directly involving former clients, those relationships can nonetheless hinder the Division’s public image and cast a long shadow over its enforcement efforts. Of course, many wonderful people do high-quality legal work for defendants, which is important in an adversarial system. But at this particular moment in history, the ideal Division AAG should have a consistent, demonstrated commitment to enforcement—not a long track record of actively choosing to oppose it.

“At this particular moment in history, the ideal Division AAG should have a consistent, demonstrated commitment to enforcement—not a long track record of actively choosing to oppose it.”

Recommendation #2: Increase Division funding and pay.

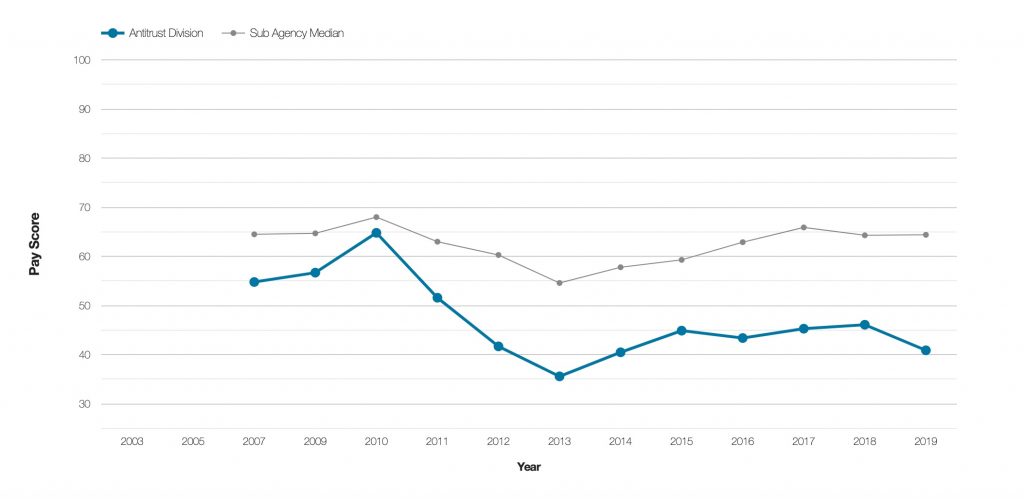

The Division faces a serious pay gap, one that will be impossible to address without additional funding from Congress. Starting salaries for first-year associates at large law firms now top $200,000 per year. Yet an entry-level trial attorney at the Division makes far less—in DC, for example, they currently start at salaries as low as $72,750 per year. Little wonder, then, that pay has become a serious morale issue. As the OPM survey shows, this has only worsened over time:

Money should never be the only—or even the primary—reason to practice with the Division. But living in DC, New York, San Francisco, or Chicago is an expensive proposition. Many attorneys, especially those starting out at the low end of the pay scale, carry significant student-loan debt. Increasing pay is increasingly essential to attracting and retaining innovative, dedicated, and diverse enforcers. As former FTC chairman Bill Kovacic recently warned, without “dramatically” increasing pay, the federal antitrust agencies cannot effectively carry out their mission. Fortunately, this is a rare area of bipartisan consensus in Washington. With the agencies already engaged in high-stakes antitrust litigation against Google and Facebook, Congress should act sooner rather than later.

Recommendation #3: Use existing funds wisely.

Regardless of funding levels, Division leadership must think long and hard about how to stretch each dollar. One way to increase morale without creating new positions or new programs is to look inwards: promote from within the Division wherever possible. The Antitrust Division is packed with highly skilled attorneys and economists, many of whom have dedicated their entire careers to enforcing antitrust laws. They’ve been in the trenches with their colleagues. Imagine how it would feel if an opportunity for advancement were to open up, only to be filled by someone who’s been raking in a far bigger salary in private practice opposing your enforcement efforts.

That said, not all hiring from outside the Division should be verboten. But given the disastrous state of staff morale, the strong presumption should be in favor of opening up pathways for internal development and advancement.

When circumstances do require using outside resources, Division leadership should closely evaluate whether they are maximizing return on investment. Antitrust litigation has become staggeringly expensive, due in part to the use of a small circle of very well-compensated expert economists. Biden’s Antitrust Division should ask whether it really needs to keep hiring exclusively from the same tiny pool. Are other experts available who might offer similar—or even higher—quality work and do so at a lower cost to the Division?

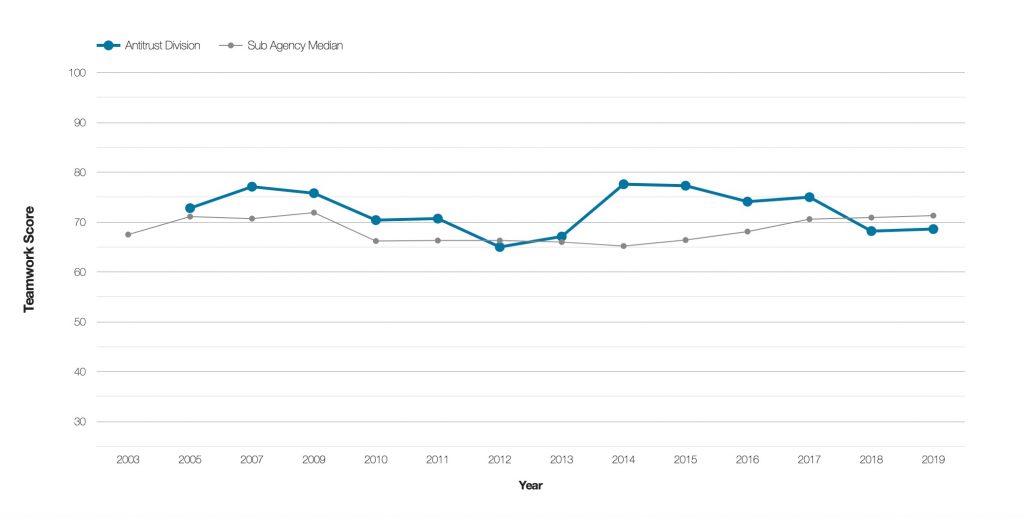

Even as overall morale has dropped precipitously, the OPM’s annual survey shows that Division staff can—and do—continue to work extremely well together. Despite a slight downturn over the past few years, “teamwork” has been a consistent bright spot at the Division.

Incoming leadership at the Antitrust Division faces an incredible opportunity. Interest in antitrust is as high as it’s been in decades. These moves would be a necessary first step toward a revitalized Division, one ready to take on the pressing challenges of Twenty-first Century antitrust enforcement.