A new paper documents how LAPD officers responded to two police reforms—one in 1998 and one in late 2002. It finds that when public complaints were used to investigate officer behavior, officers disengaged from policing.

After years of Black Lives Matter protests and the recent civil unrest following the death of George Floyd, many cities and states have begun exploring potential police reform measures. Virginia recently banned no-knock warrants. Maryland lawmakers are considering state-wide standard for use of force, expanded use of body cameras, and improving transparency by providing greater public access to police misconduct records. And on March 1, the Biden administration publicly announced its support of a police reform bill that would ban chokeholds, end no-knock warrants for drug cases, and overhaul qualified immunity protections for law enforcement.

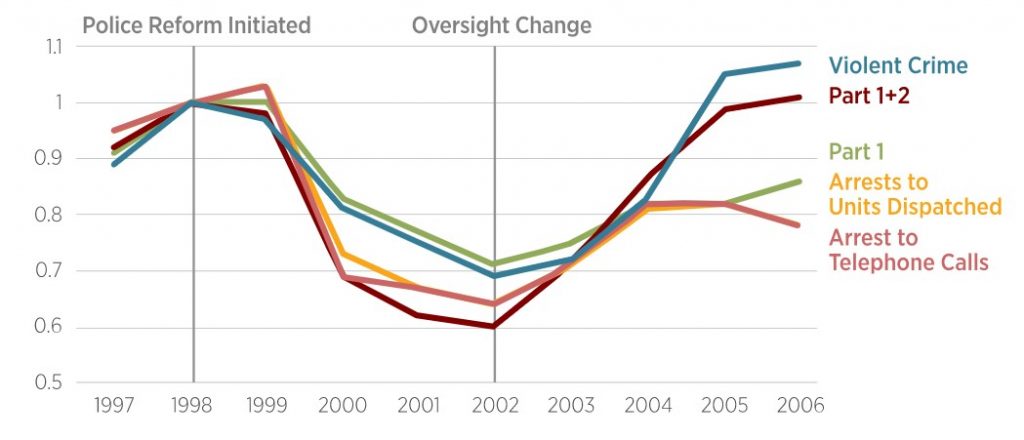

However, police reform measures might have unintended consequences. A new paper from the Stigler Center’s working paper series, “‘Drive and Wave’: The Response to LAPD Police Reforms After Rampart,” by Canice Prendergast, professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, documents how LAPD officers responded to two police reforms—one in 1998 where office accountability was increased and then in 2002 when the accountability fell. It finds that in response to the first reform, which utilized public complaints as a way to investigate officer behavior, LAPD officers disengaging from policing. This police withdrawal, in turn, resulted in a significant drop in arrests and an increase in homicides.

Rampart

In the late 1990s, the LAPD Rampart scandal revealed widespread police corruption among members of an anti-gang unit called CRASH, short for Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums, at the Rampart Precinct. One member of the squad was accused of planning and carrying out a bank robbery. Another CRASH officer was shot by an undercover LAPD officer in self-defense. And cocaine kept disappearing from the evidence room. It was stolen by Officer Rafael Perez, who checked out cocaine evidence on number of occasions and replaced it with Bisquick. Perez cut a deal with the investigators and offered evidence on three other Rampart CRASH officers. As the investigation into the behavior of these officers unfolded, more than 100 convictions were overturned and LAPD settled lawsuits amounting to $125 million.

To ensure that something like this wouldn’t happen again, LAPD introduced a new policy in 1998 where the Internal Affairs Division would investigate all complaints filed against officers. Complaints against officers soared, and so did the number of officers who were disciplined. Complaints increased from 2,712 in 1997 to 6,965 in 1998, 6,830 in 1999, 9,244 in 2000, and 7,450 in 2001. In the early 1990s, an average of 13 officers per year were removed from the force for wrongdoing. In 1998, 55 officers were removed, and 44 were removed in 1999.

”In three years, although people say the civil-service system is very difficult to work with, we have disciplined over 800 officers and terminated 113,” Bernard Parks, the then chief of police, told the New York Times in 2000. ”We have had 200 officers leave the department while being investigated. We have had a number of officers that we refused to promote because of their prior disciplinary history.”

“Complaints increased from 2,712 in 1997 to 6,965 in 1998, 6,830 in 1999, 9,244 in 2000, and 7,450 in 2001.”

The average investigation took almost 9 months in 1999 and 6.3 months in 2000, but with some complaints taking more than a year to resolve complaints started piling up. By the end of 2000, 9,512 complaints were pending against officers, and 9,122 were pending in 2001. While complaints were being investigated, officers would not be promoted or transferred.

The Unintended Consequences of Police Reform

While the main purpose of the new complaint process was to cut down on corruption within the police department, it also had an effect on how the police carried out their duties. A 1999 survey of the officers found that 80 percent of them feared “being punished for an honest mistake.” More than half, at 58 percent, said that their “career has been harmed by a complaint made by a member of the public.” A report reviewing the operation, policies, and procedures of the LAPD in the wake of the Rampart scandal reported that in an effort to avoid complaints, police officers changed the way they policed the streets.

“[M]any officers say they will act only in response to radio calls to avoid having to justify why they approached an individual. Absent a radio call, we have been told repeatedly, officers often choose to “smile and wave.” These observation are reinforced by the fact that in calendar year 2000, a year in which crime rates are rising, there has been a significant decrease in arrests, citations, and officer-initiated activities. Failing to address observed criminal activity, of course, is improper conduct by a police officer. Nonetheless, in written comments in response to our survey, a number of officers admit that they no longer do “observational” or “proactive” policing. Even more confirm that it has become a common belief that the way to stay out of trouble and to increase one’s chances for promotion is to respond to radio calls, and to do no more than is absolutely necessary.”

There are some so-called “victimless” crimes like narcotics and prostitution, where there would typically be no radio call and where arrests are usually a result of an officer observing the crime. From 1998 to 2002, narcotics arrests fell by 45 percent and prostitution arrests by 40 percent. According to Prendergast, the arrest-to-crime rate fell by 40 percent from 1998 to 2002 for all crimes, those with victims and victimless. For crimes with victims such as burglaries and assaults, the arrest-to-crime rate fell by 29 percent.

As a result, there were new attempts to alter the complaint process. For example in 2001, the Department of Justice mandated that complaints had to be resolved within five months, but only about half of investigations were completed within that time. In November 2002, the process changed again. Commanding officers could now dismiss complaints they thought frivolous. Prendergast found that “beginning in 2003, sustained complaints fell dramatically, and disciplinary measures across the board became less likely, even when an investigation ruled against the officer. This change to the complaints process was not publicized.” Arrest rates immediately increased, and by 2006 the arrest rate for all crimes returned to its 1998 level.

Police officer disengagement didn’t just have an effect on arrests, but also on crime. Homicides rose 49 percent from 1998 to 2002. In the three years after 2002, once the oversight was reversed and arrests went up, homicides fell by 30 percent.

“Drive and Wave”

The changes in the complaint process—both in 1998 and 2002—are the focus of Prendergast’s new paper, in which he explores the trade-offs between engagement and a likely complaint that officers consider while policing. According to him, “officers responded to the first reform by disengaging from policing, actions they labeled ‘drive and wave.’” The paper documents changes in rates of arrest for crimes with victims (Part 1) and without (Part 2) as evidence of the “drive and wave” disengagement.

LAPD Arrests-to-Crime Rates (1998=1)

LAPD Narcotics and Prostitution Arrests (1998=1)

To check his “drive and wave” hypothesis, Prendergast compared LAPD response to Part 1 crimes like burglary or assault, which have victims and get called into a station, with LAPD response to Part 2 crimes like drug deals and prostitution that depend on active street policing. In line with Prendergast’s “drive and wave” theory, narcotics arrests fell by 44 percent from 1998 to 2001, and then increased by that amount afterwards.

To determine if these results were mainly driven by the changes to the way that LAPD handled complaints against its officers, Prendergast compared LAPD data to that of the Los Angeles Sheriff Department, which polices a range of unincorporated cities in Los Angeles, as well as California Highway Patrol and the FBI, who also make arrests within the LAPD’s jurisdiction. None of the three agencies experienced the swings in arrest-to-crime rates during that time that the LAPD did. Prendergast also analyzed other data collected by LAPD after 2001 and found that after the oversight was reversed, use-of-force per crime rose by 35 percent between 2001-2002 and 2003-2006, while street stops rose by 70 percent.

Takeaway

According to the paper, among the unintended consequences of the new complaint process was that suspect oversight—the possibility that those approached by officers while policing would complain—was strengthened, while the voice of the victims was not. And as a result, when the complaint procedures first changed, the behavior of the police changed too, and not for the better, since police withdrawal resulted in fewer arrests and more homicides.

The lessons from Rampart still hold today and are quite relevant as cities explore different ways to reform their police departments. However, these findings should not be interpreted as “an argument against police reform,” writes Prendergast, but as a warning about obstacles that will need to be addressed. Future oversight reform should incorporate oversight by a key constituency that was ignored by the LAPD—the victims of crimes.