Dozens of foreign citizens linked to corruption, embezzlement of public funds, organized crime, and tax crime have opened companies in Luxembourg, seemingly without raising red flags, suggesting a failure in the regulation of the corporate industry.

Editor’s note: This piece was republished with permission from the Organized Crime and Corruption Report Project (OCCRP). A longer version of the original piece can be found here.

In 2019, an announcement appeared in the Spanish press. A major stake in one of Spain’s largest weapons manufacturers, Maxamcorp, had been sold. The Spanish government approved the deal, and everything seemed to be proceeding normally. But for those following closely, the situation was bizarre: Nobody knew who the real buyer was.

On paper, it was Prill Holdings, a company based in Luxembourg. But who was behind Prill? The only available information about the company’s owners showed two firms registered in the Cayman Islands. These are linked to a US private equity company, Rhone Capital, but little else is known about them. To some, the opacity was disturbing.

“It is unacceptable that the Spanish government is greenlighting a company to operate in a sector that has many human rights implications without knowing who is behind it,” said Susana Ruiz, Tax Justice Coordinator for Oxfam International.

Prill isn’t the only mysterious company registered in Luxembourg. Though it’s one of the smallest nations in the world, Luxembourg hosts an enormous amount of financial activity, almost all of it originating abroad. Nearly 90 percent of companies registered in the country are controlled by non-Luxembourgers. At least 266 members of the Forbes billionaire list—none of whom are locals—have companies there. And about 40 percent of Luxembourg companies were set up merely to hold assets, without generating any other economic activity.

Essentially, the country functions as an offshore hub in the heart of Europe.

Many Luxembourg companies are in full compliance with the law and exist for legitimate reasons. But others are owned by people with political exposure, corrupt officials, and even organized criminal groups.

The biggest draw might be Luxembourg’s reputation for secrecy. This has made it a magnet for people seeking to “disconnect themselves from their holdings,” says Gabriel Zucman, an associate professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley.

Holding assets in Luxembourg companies “is going to make it harder for authorities to link assets to their owners, which is going to make it harder for authorities to investigate cases of corruption or fraud or tax evasion,” he said. “That’s the key service that’s provided by this segment of the financial industry.”

So much Russian capital has found its way to Luxembourg—and back again—that the tiny European state is now one of Russia’s biggest foreign investors. “That is not because Luxembourg is investing to build factories in Russia,” says Benoît Majerus, a history professor at the University of Luxembourg. “It is clear that it is Russian money circulating in Luxembourg and returning to Russia.”

Italian prosecutors say members of the ’Ndrangheta mafia have flocked to Luxembourg, seeing it as an “extremely attractive” place to keep ill-gotten cash out of reach. And investigators in at least three South American countries are looking into allegations that political figures stashed bribes in Luxembourg companies.

“About 40 percent of Luxembourg companies were set up merely to hold assets, without generating any other economic activity.”

“We are worried,” Laurent Lim, a policy officer for the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Financial Stability, told OCCRP. “Luxembourg is known for this matter of taxation, but we must also start talking in terms of money laundering.”

“Until last year there was no transparency,” he added. “Until last year a company could be created and there was no way of knowing who was the beneficial owner.”

Now, there is—at least, in theory.

In 2019, to comply with an EU directive on anti-money laundering, Luxembourg set up a new register that required the 124,045 companies registered there to identify their ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs). UBO describes who actually controls the income or assets of a company, which in many cases is not the same as the person who registers it— sometimes known as the “legal owner.” Although there is no universal definition of a UBO, many jurisdictions, including Luxembourg, are choosing to define it as anyone who controls at least 25 percent of voting rights in an enterprise.

Luxembourg was one of the first countries in Europe to establish a public UBO register, and anti-corruption campaigners see it as a major step forward.

But as implemented, the database has some critical limitations. One of the biggest is that it is only searchable by company name, not by owner. This makes it difficult for journalists and members of the public to determine who owns what.

Last year, however, French newspaper Le Monde scraped the database, obtaining millions of documents that reveal all the companies registered in Luxembourg—and their newly declared UBOs. OCCRP’s data and technology teams made these documents fully searchable, then opened them up to journalists from media outlets around the world, allowing them to search by owner for the first time.

The names they found were striking. Mingling alongside billionaires, singers, actors, and star sportsmen were compromised officials, leaders of criminal organizations, and friends and family members of prominent political figures from around the world.

Among the beneficial owners spotted by journalists were:

- An arms dealer at the center of one of the biggest corruption scandals in France;

- The Kremlin-connected leader of one of the largest Russian criminal organizations;

- An ex-son-in-law of Tunisia’s former dictator;

- A close confidante of Serbia’s president

- The teenage children of a Russian oligarch

- A Turkish businessman accused of being linked to a $511 million tax scheme;

- An Indonesian palm oil magnate considered responsible for the destruction of thousands of hectares of virgin forest; and

- Several members of the ’Ndrangheta, Italy’s most powerful criminal group.

Given the advantages of secrecy jurisdictions, the presence of criminals and politicians should be no surprise, Zucman says.

“Who are the users of these offshore tax havens?” he asks. “It’s a mix of tax evaders, tax avoiders, criminals, money launderers, corrupt business people or political elite.”

We can assume that these names were intended to stay hidden. Many of these companies were registered in the name of figureheads so their ultimate owners’ names would not appear in public.

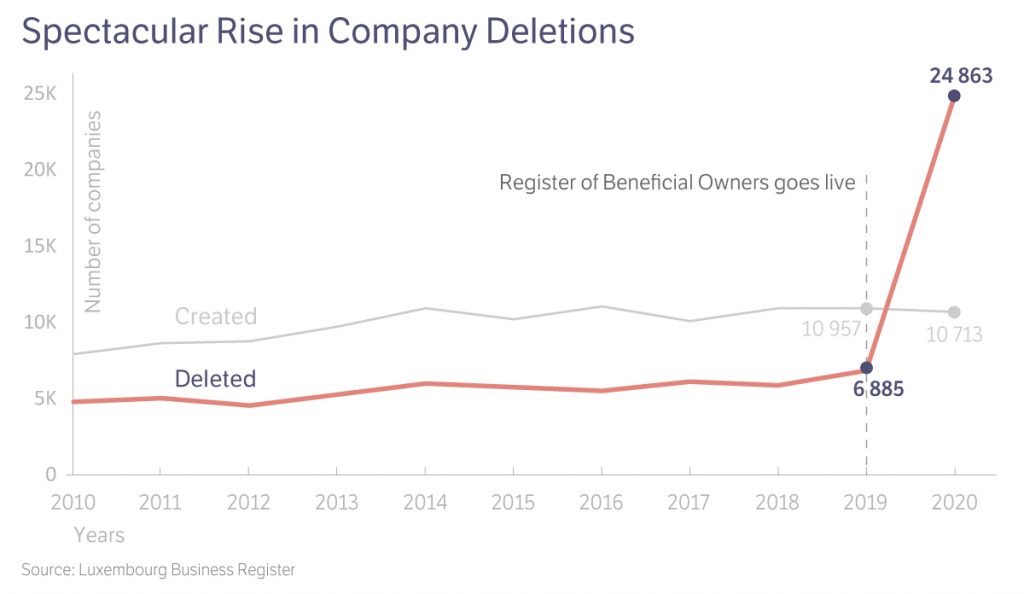

In 2020, the year after Luxembourg’s UBO register went live, there was a huge rise in company deletions. For the first time in the country’s history, more companies were deleted from the books than created.

Even within Luxembourg, there is a growing realization that the country needs to reckon with the dark side of its vast foreign capital inflow, which as of 2019 amounted to over $5 trillion in portfolio investment— making it second in the world after the US.

“The Luxembourg government is well aware that this success also involves exposure to the growing and evolving threat of money laundering and terrorist financing,” the country’s Finance Ministry said in a 2018 report. Another report, two years later, underscored that laundering of foreign criminal proceeds was “the highest threat” for Luxembourg.

The Finance Ministry told OCCRP it had “resolutely adopted tax transparency” and was in full compliance with EU standards. In a pre-emptive statement on the OpenLux project, the government of Luxembourg said it was in line with all EU rules on tax transparency and combating money laundering.

It also reserved the domain name openlux.lu and produced its own FAQ on the UBO register, based on queries made by journalists. It said the register was “a strong act of transparency” and noted that most EU countries did not yet have public databases.

“Given that Luxembourg is fully compliant with and has implemented all applicable EU and international rules and standards with regards to tax transparency, the fight against tax abuse as well as AML/CTF [anti-money laundering and countering terrorist financing]—and even gone beyond these requirements—Luxembourg rejects the claims made in these articles as well as the entirely unjustified portrayal of the country and its economy,” the government said.

By all accounts, the situation today is better than it was five years ago. But experts say there are still many problems with the way the database is being implemented, a complaint borne out by OCCRP’s own analysis.

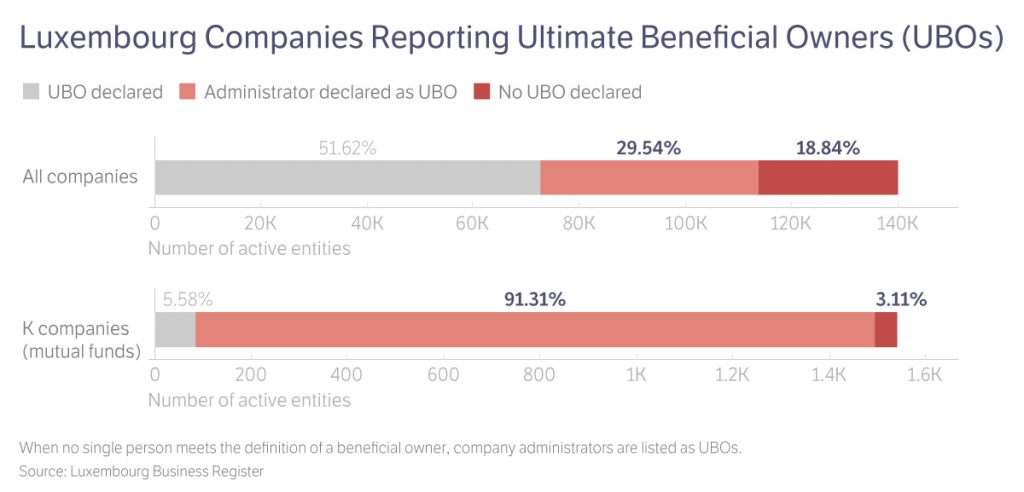

The case of Prill Holdings is a good example. The company has not identified its beneficial owners, so its corporate administrators were listed as UBOs by default. We found that administrators were listed as UBOs for almost a third of all Luxembourg companies in the register.

For so-called “K companies,” a kind of mutual fund, this number rose to over 90 percent, since so few of them have even a single investor who meets Luxembourg’s definition of a UBO.

Out of all investment funds, around 80 percent did not report real UBOs, according to a new analysis of OpenLux data.

Transparency International and the Anticorruption Data Collective cross-referenced the data these funds provided to Luxembourg with disclosures to the US Securities and Exchange Commission and found “significant discrepancies” in the 719 funds registered in both jurisdictions. It found 112 funds that reported their beneficial owners to the US government, while only 17 of these did the same in Luxembourg.

“This discrepancy suggests that either the funds are misrepresenting their ownership structure to the [Securities and Exchange Commission], or failing to abide by the rules laid out in the Luxembourg [register],” Transparency International wrote.

Either scenario, the authors said, could be grounds for penalties, illustrating the need for better verification measures and stronger enforcement.

(Luxembourg’s government said in a response that the sources were not comparable. “It is therefore not really possible to draw conclusions based on apparent discrepancies, and it is certainly wrong to infer that information in Luxembourg’s [register] is false or incomplete,” the government said in an online statement.”)

“What Luxembourg has done is as if they’ve removed … the first layer of the onion,” said Ruiz. “But you have to get to the owner and the ultimate beneficial owner of these companies.”

“It is necessary not only that the register exists, but also that it is effective.”

Promise and Reality

The very existence of public UBO registries is a major step forward for transparency.

But experts point to problems with the way Luxembourg’s is set up.

In addition to not being fully searchable, the database is incomplete. A year after its creation, only 52 percent of Luxembourg’s companies have reported their real owner, according to Le Monde’s analysis of the registration data. (Luxembourg authorities denied this, saying the true figure is closer to 88 percent).

Of the other 48 percent of companies, more than 68,000 still haven’t declared a UBO. About 40,000 aren’t required to do so, because they have no UBOs who hold more than 25 percent of the company. But in 26,000 of these cases, Luxembourg authorities say the companies are breaking the law, and have been forwarding them to prosecutors.

In these cases, and others, a company’s administrators are listed in the database instead of their UBOs.

According to Transparency International, Luxembourg’s definition of a UBO—someone who controls at least 25 percent of a company—is especially inadequate due to the large number of investment funds in the country.

“The concept of an investment fund is that those individuals investing in the fund, and benefiting financially from it, are not the same as those controlling the fund and making decisions on the types of investments, among others,” TI wrote in a study. As a result, “criminals are able to layer or integrate the proceeds of crime by investing dirty money across different investment funds, while remaining anonymous as long as their investment is below the reporting threshold.”

Le Monde and OCCRP also identified dozens of cases in which the declared UBOs were children, dead people, or obvious proxies.

Officially, failing to declare a UBO or offering false information is punishable by a fine of between 1,500 and 1.25 million euros. But in practice, enforcing the measures is a daunting task, and there is only one publicly known case of a company being punished for a failure to declare. The fine was 2,500 euros.